Special Collections and University Archives (SC/UA) closed the New Jersey Reading Room on October 1 to allow staff to work on flood recovery activities. The closure will remain in effect for the rest of the academic year.

Hurricane Ida severely impacted SC/UA, so we are taking these measures to ensure the long-term preservation of collections and improve the storage and research environment. No collections were destroyed but there was extensive flooding and damage to the storage areas necessitating moving 27,000 linear feet of collections to safety.

Remote reference, scanning, and instruction will temporarily close on October 15 as we prepare collections to move off-site. We anticipate that a large portion of our collections will be inaccessible for at least a year.

Our two top priorities are preserving our collections and providing access to them. As we secure the material, we are working to find ways to provide access to limited parts of our collections to enable research and instruction to continue. We’ll provide updates on access during renovation on our website and here on “What Exit?”

If you have questions, please contact us.

We apologize for this inconvenience and appreciate your patience and understanding.

Author: Christie Lutz

The Long Journey of the Griffis Collection Finding Aid, Now Online

By Fernanda Perrone, Curator of the William Elliot Griffis Collection

The William Elliot Griffis Collection documents the life, career, and connections of the man who has been described as “the most important interpreter of Japan to the West before World War I.” William Elliot Griffis was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1843 and attended Rutgers College from 1865 to 1869. At Rutgers, Griffis befriended some of the earliest Japanese students to attend an American college, and developed a lifelong fascination with that country, which had recently opened to Westerners. After graduation, through his Rutgers connections, Griffis was offered the opportunity to teach natural sciences in Japan. Leaving in fall 1870, Griffis spent eleven months teaching in Fukui in western Japan before moving on to a position in Tokyo. He was joined by his sister Margaret, who kept house for him, tutored students, and eventually gained an appointment at the first government school for girls. Although Griffis and Margaret left Japan in 1874, he would spend the next fifty years writing, lecturing, and collecting material about Japan, producing more than 20 books, hundreds of magazine articles, newspaper editorials, and reference book contributions.

As well as keeping diaries and letters from his time in Japan, throughout his life Griffis collected publications, manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera related to Japan and East Asia. Indeed, Griffis’ most enduring legacy is his archival collection of over 250 boxes, which was donated to Rutgers after his death on February 5, 1928. Reputedly his wife Sara Griffis filled half a box car of a train with Griffis’ collection for the slow journey from his home in upstate New York to New Brunswick. Arrangement and description of the Griffis Collection began as early as the 1930s with a grant from the American Council for Learned Societies. After a hiatus during the Second World War, cataloging resumed with the collection’s rediscovery in the 1960s and continued under a succession of curators into the 2000s. A finding aid in paper format was created in 2008, which numbered 288 pages. In the following years, a 69-page inventory of photographs, a 37-page list of oversize materials, and several other sections were completed.

While SC/UA faculty and staff have labored to mark up finding aids using Encoded Archival Description and make them discoverable on the Web, no one had the time or fortitude to attempt the Griffis finding aid. Only during the pandemic, with the uninterrupted time allowed by remote work did Processing Archivist Tara Maharjan take on the challenge of encoding this behemoth. Working closely with Griffis Curator Fernanda Perrone, Tara began work in October 2020 and finished in March 2021. Today the finding aid can be found on the SC/UA website at http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/ead/manuscripts/griffisf.html, where it is keyword searchable and discoverable by Google. Parts of the collection have also been microfilmed and digitized by Adam Matthew Digital and can be viewed through the Area Studies Japan database. Photographs of early Japanese students at Rutgers can be viewed in RUCore: for example, this portrait. The rare and unique Korean photographs from the collection have been digitized and will ultimately become available for research. Some can be viewed at SC/UA Primary Source Highlights.

Congratulations and sincere thanks are owed to Tara Maharjan for this amazing accomplishment, which will bring the collection to a wide audience of students, scholars, and interested individuals, stretching from New Brunswick to Japan and beyond.

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections, Part Three

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

This is the third and last post in a short series featuring final projects from the Rutgers Byrne First-Year Seminar I taught in Fall 2020, “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture.” You can read about the course and the final project, in which students envisioned their own pop culture archives, and check out other student projects, here.

This project, An Old Way to Listen to Music: Archiving a CD Collection, by Carmen Ore, Rutgers Class of 2024, wraps up the series with a consideration of how one’s connection to a particular type of music can extend to the media form.

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections, Part Two

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

This is the second in a short series featuring final projects from the Rutgers Byrne First-Year Seminar I taught in Fall 2020, “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture.” You can read about the course and the final project, in which students envisioned their own pop culture archives, in this post.

This project, entitled Archiving Goodness, is by Sarah LaValle, Rutgers Class of 2024. Sarah’s archive, like our previously featured student’s archive, Domination of Face Masks in 2020, is another timely project that came out of this course.

Public Event: Exploring Special Collections and University Archives: Black History Resources

Announcing Exploring Special Collections and University Archives, a new webinar series from Rutgers–New Brunswick Libraries Special Collections and University Archives.

The webinars will feature talks, virtual tours, and demonstrations by our curators and scholars showcasing the rich resources of our historic and cultural collections.

You’re invited to the first webinar of the series, “Black History Resources.” Curators Erika Gorder and Christine Lutz will discuss Black history resources in Special Collections and University Archives.

Event Details:

Wednesday, February 17, 2021, via Zoom

4:00-5:00pm (Eastern Time, US and Canada)

Questions? Contact Special Collections & University Archives

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

For the past two fall semesters, I have taught “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture,” a course I developed for the Rutgers Byrne First Year Seminars. In the course, students engage in active, hands-on learning to explore archives and special collections and how they can be used for research. We examine popular culture collections in Rutgers’ Special Collections and University Archives and elsewhere that document a wide range of topics such as the New Brunswick music scene, video games, cookbooks and restaurant menus from around the Garden State, zines representing a variety of subcultures, Women’s March and other protest movement posters, and Jersey Shore memorabilia.

The goals I set for students in this course include developing an understanding and appreciation of archives and special collections; developing primary source research skills and becoming careful interpreters of documents, images, and objects; understanding how critical factors such as ethnicity, race, gender, and class are documented and perpetuated in popular cultural materials; and to learn to think about what is included and excluded in archives and special collections, and why. We also learn from each other as we share, debate, and think creatively about expressions of popular culture.

I will be sharing some of the students’ final projects (some anonymously) for the Fall 2020 course, in which they envision their own pop culture archive, and present their concept for an archive, in narrative form or in a slide show.

Here is our first student project, a very timely archive, entitled Domination of Face Masks in 2020.

2021 Greetings

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

Happy New Year from Special Collections and University Archives. In early 2021, we are reflecting on the fact that that 2020 was a difficult and challenging year for so many. Like most of our colleagues in archives and special collections around the country, and indeed around the world, Special Collections and University Archives (SC/UA) faculty and staff have had to redirect our efforts to increase remote services. In summer and fall 2020, we scrambled to enhance access to digital materials, offer Zoom research consultations, and provide remote classroom instruction. We probably made more PDF copies of materials for researchers than any year to date!

While we look forward to the day we can reopen our reading room to researchers near and far, we continue to provide research support, instruction, and information for enjoyment and edification as our faculty and staff work (primarily) remotely. To that end, we’d like to share a few highlights of the work we have been doing to support Rutgers faculty, students, and staff; researchers around the state of New Jersey; and students and scholars from all corners of the world.

Digital Resources

We are excited to share a new digital resource, “Special Collections and University Archives Primary Source Highlights,” a site that makes accessible a trove of images we have scanned for researchers over the years. The site also features images from an ongoing project to scan the Sinclair New Jersey Postcard Collection. While “Primary Source Highlights” is still in its infancy, we are adding images regularly, so we encourage you to check back periodically.

“Primary Source Highlights” will be included in the SC/UA Digital Resources Guide we created in the fall. This guide continues to serve as a one-stop-shop for centralized, easy access to SC/UA’s digitized resources.

During the fall semester, we started a project to revamp and update the content of our subject guides. These guides serve as a useful gateway to our collection strengths, and are a particularly good resource for students looking for paper topics, or to see what materials SC/UA holds on a particular topic.

The New Jersey Digital Newspaper Project is continuing to digitize historical New Jersey Newspapers for inclusion in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America website. Recent additions include the Gloucester County Democrat (1878-1912), Morris County Chronicle (1877-1914), Pleasantville Weekly Press (1892-1911) and The Pleasantville Press (1912-1914).

The NJ Digital Newspaper Project blog provides further information about the project and links to all NJ newspapers digitized to date. These newspapers have been digitized as part of the National Digital Newspaper Program, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Reference and Instruction

We will continue to provide instructional support this spring. If you’re looking for resources for your course, or would like a curator or archivist to provide instruction for your class, feel free to send a message to scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu and your request will be directed to the appropriate faculty or staff member. For general requests or questions, feel free to contact Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services at christie.lutz@rutgers.edu.

Looking for a quick way to introduce your students to the mission and work of SC/UA, or add a video to your Canvas course? We’ve compiled our videos, including a brief overview of SC/UA aimed at undergraduate students, and a couple of fun quizzes which in one spot. Check out https://libguides.rutgers.edu/scuavideos

You can always write to our reference account at scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu with questions and scanning requests. We are continuing to waive our reproduction fees this semester.

Exhibits and Events

2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) granting women the right to vote. Explore our most recent exhibition, On Account of Sex: The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage in Middlesex County or listen to a talk by Ann D. Gordon, “Bringing the Story Home: Agitating for Woman Suffrage in New Jersey.”

Photographer and author Barbara Mensch delivered the 34th annual Louis Faugères Bishop III lecture, “In the Shadow of Genius: The Brooklyn Bridge and Its Creators,” in November, 2020. Mensch was inspired by SC/UA’s Roebling collection to create her recent book by the same name (Fordham University Press, 2018).

What else is happening?

We’re starting to roll out a new look and feel to our finding aids, via ArchivesSpace, a platform that will provide easier searching of our manuscript collections and a uniform look and feel.

Along with the rest of Rutgers University Libraries, we are developing a new website that will be more user-friendly and feature updated content.

You can always check the SC/UA website and social media feeds (links in the column to the right, plus the New Brunswick Music Scene Archive on Facebook) for the latest news, events, and changes in operating status and/or services.

Nicholas Culpeper, Elizabeth Blackwell, and the Lure of Herbalism

Happy 2020! We’re kicking off the new year with this piece by Emily Crispino, a graduate student in the Library and Information Science Department at Rutgers’ School of Communication and Information. During the fall 2019 semester, Emily was a public services intern in Special Collections and University Archives. In this position she assisted researchers at our busy reference desk and researched and responded to a variety of inquiries from around the world related to New Jersey history and genealogy through our virtual reference service.

~~

While I cannot claim enough knowledge to call myself an herbalist, my shelves full of dried plants would seem to qualify me as an herbal enthusiast. I brew a yearly elderberry syrup to ward off winter colds, drink teas for just about every ailment, and occasionally concoct something new after consulting my personal library of herbals. Written by everyone from New Age gurus to a former botanist for the USDA, these books outline the medicinal properties of plants, accompanied by physical descriptions, dosage information, and recipes for preparations such as salves and tinctures. Often, photographs or botanical sketches accompany each entry.

Ideas about health and medicine have changed a great deal over the last 300 years, but the herbal format has remained largely the same. Special Collections and University Archives holds many examples of historical herbals, including two that I would like to examine in this post. The first is a 1798 edition of Nicholas Culpeper’s English Physician and Complete Herbal, first issued in 1652. The second is A Curious Herbal by Elizabeth Blackwell, a 1751 edition of a work first published in 1737. Just like my New Age gurus and government workers, Culpeper and Blackwell approached herbalism from entirely different points of view. Yet both books are written in the service of healing, designed to help people help themselves.

~~

Nicholas Culpeper was a character to say the least, boasting a colorful career as an herbalist, astrologer, and sometime soldier against the King during the English Civil War. A non-conformist both in medicine and politics, Culpeper frequently received criticism from the more traditional physicians of his day. In 17th century London, the medical profession was dominated by the Royal College of Physicians, whose Censors bestowed licenses upon those whom they deemed worthy to practice. Culpeper loudly criticized their methods and accused them of overcharging for their services, making medical care inaccessible to the poor. In his own practice, he saw patients regardless of their financial status and examined them holistically before diagnosing and treating them. (2)

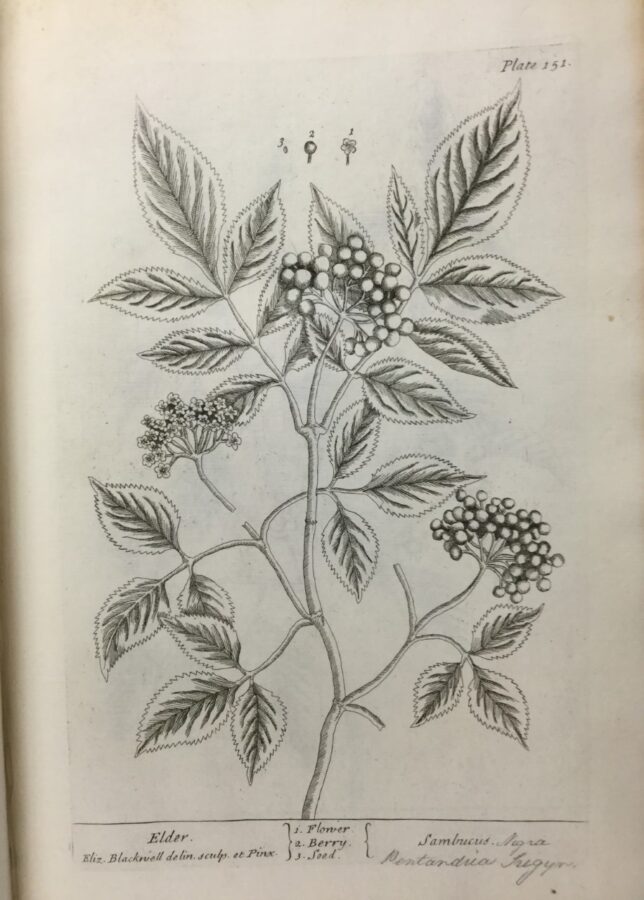

Elizabeth Blackwell’s herbal was born of more personal motivations. After her husband, a physician, was thrown into debtor’s prison, she began work on A Curious Herbal as a means to raise the funds to free him. While Blackwell was a skilled botanical illustrator and may have had some training as a midwife, she does not appear to have been an herbalist in the strict sense. The medical information in her book was primarily derived from another herbal, the Botanicum Officinale, with the permission of its author. Nevertheless, Blackwell spent years carefully sketching, engraving, and coloring plates of medicinal plants for her herbal, supported in her endeavor by a number of respected physicians and apothecaries. A Curious Herbal received significant praise and sold well, successfully paying her husband’s debts and securing his release. (1)

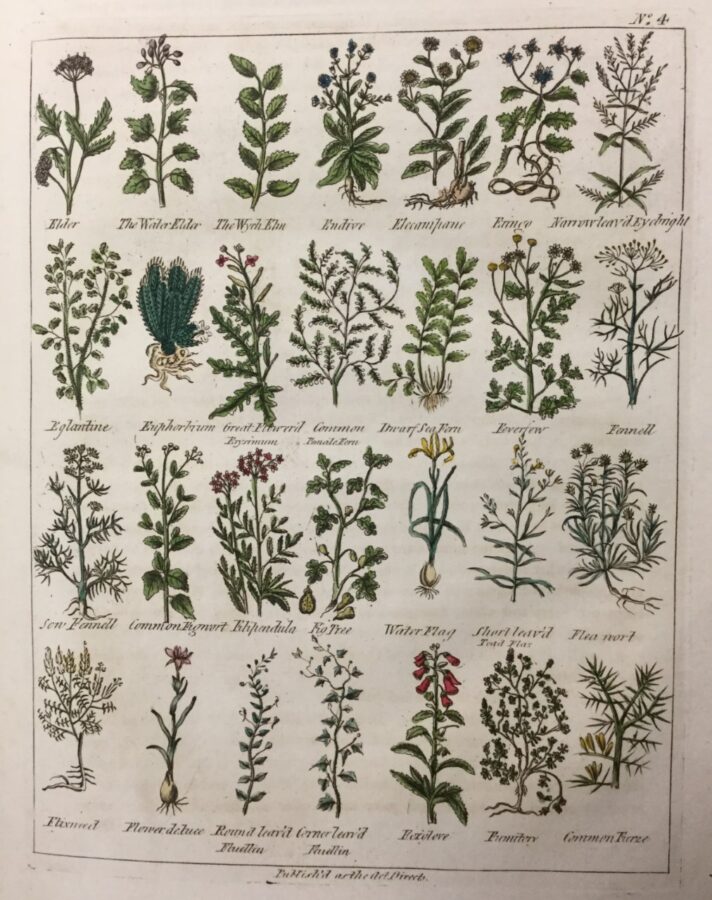

The differing backgrounds of Culpeper and Blackwell are clearly reflected in their herbals. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal contains a great deal more text than A Curious Herbal, including information on common ailments and preparing medicines in addition to his alphabetical directory of herbs. Sparing no words when explaining their properties, Culpeper’s physical descriptions of plants are surprisingly inconsistent, and he entirely neglects to describe those that he believes are commonly known. “I hold it needless to write any description of this,” he explains, referring to the elder tree, “[since] any boy that plays with a potgun, will not mistake another tree instead of elder.” The missing descriptions are not well supplemented by the illustrations, which are tiny and crammed onto designated pages.

Even these are 1798 additions, with the first edition of Culpeper’s herbal including no images at all. A Curious Herbal, on the other hand, is built around Blackwell’s illustrations. These full-page plates depict seeds, roots, and flowers in addition to the main bodies of the plants and are detailed enough to help readers identify them in the wild.

The images in the first edition were colored as well, adding to their accuracy. At the same time, the accompanying text is minimal, lacking the depth of medical information contained in Culpeper’s herbal. There is also no distinguishable order to the entries, requiring one to flip through the entire book to find information on a specific plant.

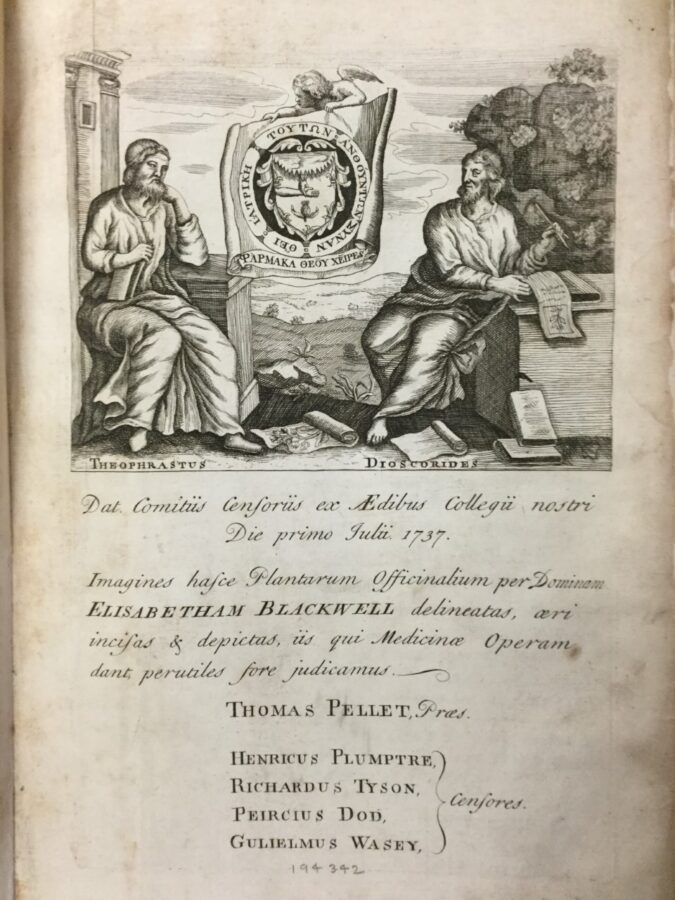

Of particular interest is the front matter of A Curious Herbal, revealing a further difference between the two books. A large illustration of ancient Greek botanists Theophrastus and Dioscorides precedes the official endorsement of the College of Physicians, signed by its then-president and Censors.

The recommendations do not end there, as a subsequent page proclaims the approval of nine more physicians and “Gentlemen.” This reception to Blackwell’s herbal could not be more unlike that of Culpeper’s, which, despite its immense popularity, received no such praise from the College. The College’s opinion of Culpeper may be summed up in a comment from member William Johnson, who proclaimed one of his works “a paper fit to wipe one’s breeches withal.” (2)

New editions of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal are published to this day, testifying to the enduring attraction of traditional medicine and home remedies. Elizabeth Blackwell too is slowly gaining recognition, and a calendar featuring her work has been released for 2020. Although they came to herbalism from very different backgrounds, those who come to it today are no less diverse. Alongside countless modern additions to the body of herbal literature, the centuries-old works of Culpeper and Blackwell have continued to inspire new herbalists—and herbal enthusiasts.

References

1 Madge, B. (15 April 2003). “Elizabeth Blackwell—the forgotten herbalist?” Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2001.00330.x

2 Wooley, B. (2004). Heal thyself: Nicholas Culpeper and the seventeenth-century struggle to bring medicine to the people. New York, NY: HarperCollins.