To mark the opening of the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection on Asbury Park as well as to help get us out of the New Jersey winter doldrums, we share this essay on Asbury Park postcards and using postcards for research by Rachel Ferrante, Fall 2017 Public History Intern 2017 in Special Collections and University Archives.

By Rachel Ferrante

There are few things as uniquely iconic as the Asbury Park postcard. The Las Vegas neons and even the Hollywood sign may be the only two cultural images that elicit similar recognition. It seems these images embody regional leisure and tourist culture, recognizable across generations. Because these signs act as visual landmarks, the images are regurgitated in popular culture. An example is the mimicking of the Hollywood sign in the Dreamworks movie “Shrek” as the sign for the fictional city Far Far Away. Using the sign as a landmark, the rest of the scene imitates Hollywood, a defining city in West Coast culture and example of opulence.

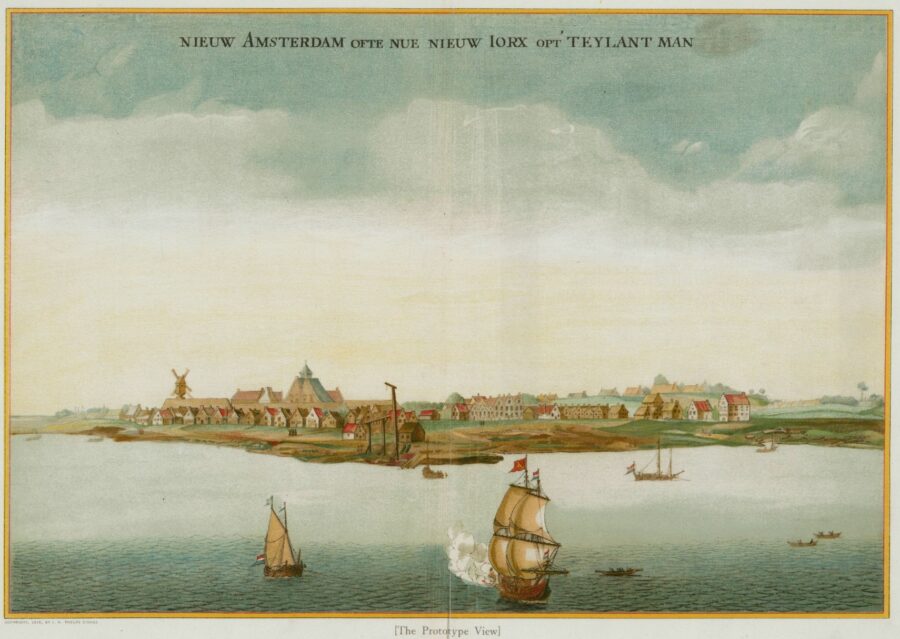

About 2,900 miles down I-80, Asbury Park is far more humble. Since its founding in 1871, Asbury Park has repeatedly boomed and busted in its cultural significance, tapping into every aspect of leisure culture one can think of. Asbury has been a physical representation of popular culture, specifically and originally for New York elites, who seem to define high culture throughout much of U.S. history. In fact, Asbury has been a center of both high culture and subculture, making it extremely relevant to the East Coast’s, if not the nation’s, cultural memory and historical interest.

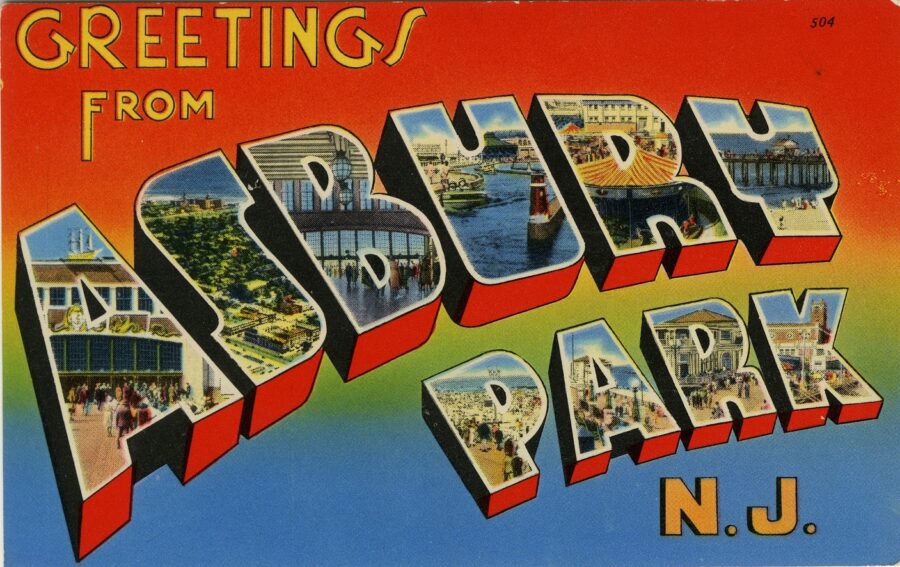

The “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.” postcard is a specific linen Tichnor style with images geared to Asbury leisure in particular. This style was applied to many postcards centered around other places as well, the likes of which include Niagara Falls and Route 66. Famously, the Asbury postcard was used as the cover of Bruce Springsteen’s breakout album by the same name. So beyond its initial iconic stature the postcard has a history of its own. When you look at the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection on Asbury, the postcards it includes tell a story of Asbury Park’s history. Paired with the other materials in the collection, it is clear the significance certain institutions or moments in time had on the area. However, there are many more layers of significance behind the postcards. They span more than 100 years of regional history that can be contextualized in national political, social, economic, and familial histories, resulting in many potential conclusions using just postcards as primary source material. The rest of this post will address the use of postcards as research tools, using examples from the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection on Asbury Park housed at Rutgers University Special Collections and University Archives.

USING POSTCARDS FOR RESEARCH

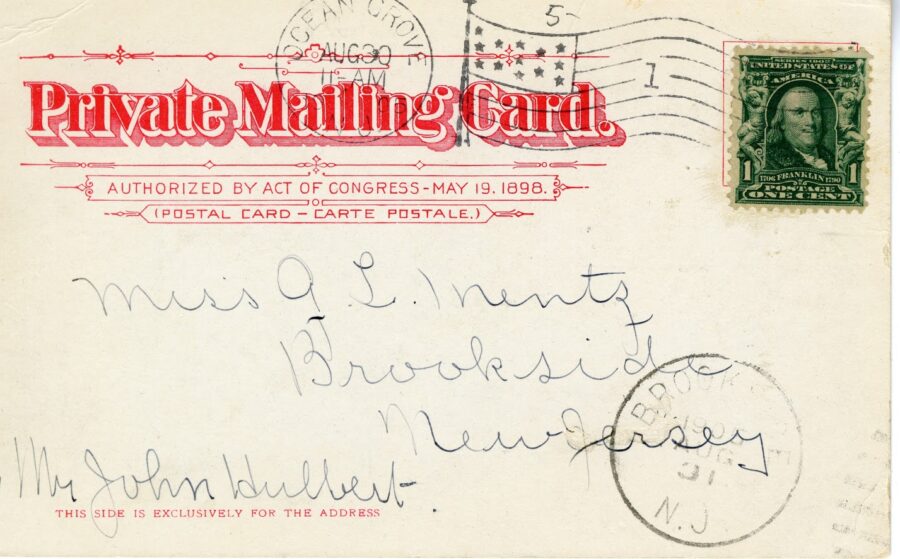

In America, the first postcard was developed in 1873 by Massachusetts’ Morgan Envelope company. These cards depicted scenes from conventions and expositions in Chicago at the height of the Industrial Revolution. The first postcard intended for souvenir purposes was actually created in 1893 with scenes from the World’s Columbian Exposition. Postcards thus have deep roots in the northern region of the country, documenting its changing history, and capturing the excitement of progress in many eras. In 1898, Congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act, which allowed postcards to be printed by private companies rather than just the post office. At this point the popularity of “Private Mailing Cards” began to skyrocket. Finally, in 1901, private companies were allowed to call their printed cards “postcards,” and after a few more years of complicated history the picture front, divided back, postcard we all know was legal and being mailed in multiple styles across (a good amount of) the country. This Golden Age of Postcards peaked in 1910, with postcards particularly popular among rural and small town women of the northern United States.

Almost all of the eras of postcards are represented in the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection. Picking one group of postcards at random I was able to see examples of the short period of time where postcards were not divided-back and the sender had to write on the front, or image part, of the postcard. There are also many beautiful examples of the lithographic style of postcards, which were specifically popular during the Golden Age period (1907-1915). Each of these provides immense interdisciplinary relevance with each layer of ink. Some of these semantics are debated among postcard enthusiasts; however, the Golden Age of postcards, no matter what the exact date range, lines up with the foundational period of American culture. One of the major things that shaped the time leading up to the 1920s was the transformation of cinema from silent to film noir. In Asbury Park in particular, cinema was a huge part of the economy, with cinema tycoon Walter Reade even running for mayor of Asbury Park. Postcards of these theaters are great primary source examples of the importance of the erection of these edifices and the positions they held as landmarks of the region. Of the six Reade theaters in Asbury, two are featured prominently in the postcard collection: the Mayfair and the Paramount. Construction and then depiction of these places reflect civic achievement as well as provide insight into the aesthetic values of the region and the time period.

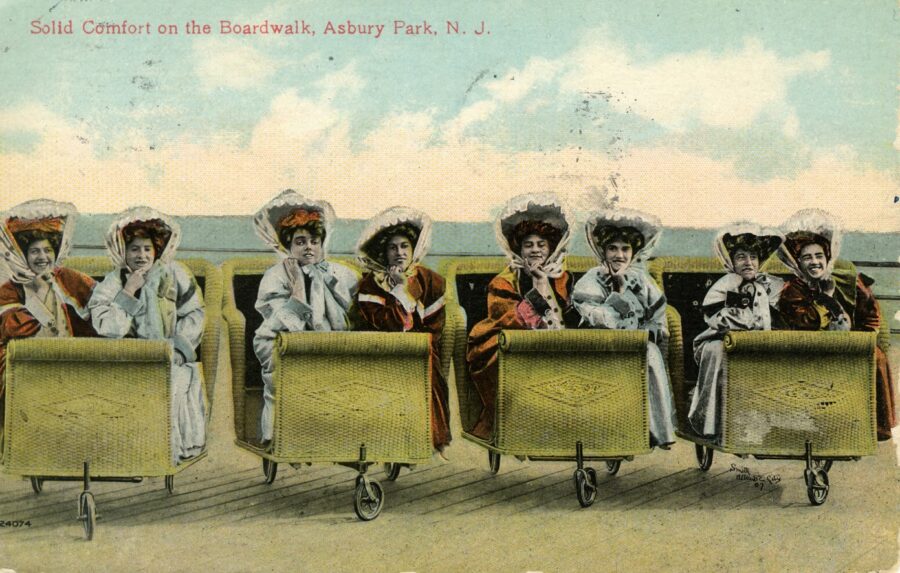

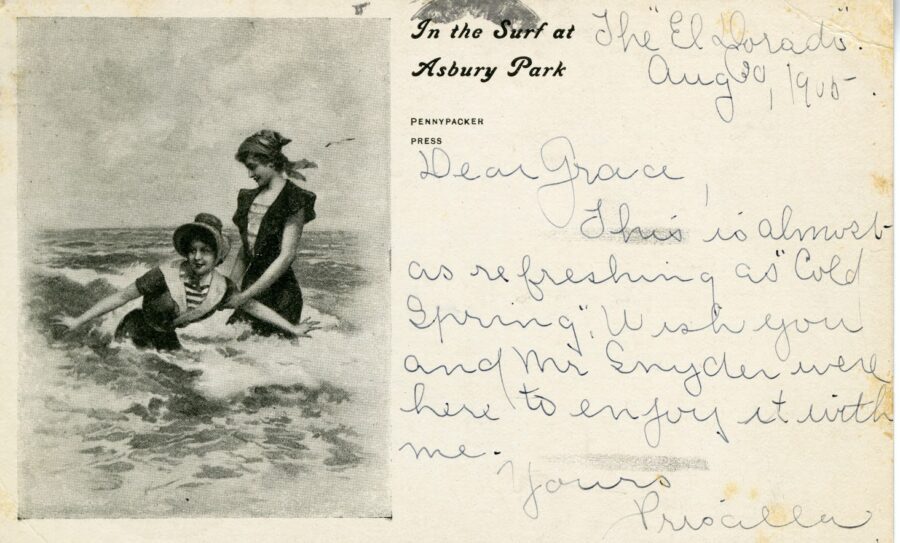

Aside from construction aesthetics many postcards provide insight into fashion. In the case of Asbury Park there are many depictions of changing beachwear trends. A 1910 lithographic postcard (seen at the start of this essay) shows a row of women in large bonnets posing coyly in carriages. The postcards in the “beach” section of the Pike Collection date from 1901 to 2001 so they document an entire century of summers, with their corresponding outfits and activities. The collection can be used to track the changing shore attractions as well. When compared to today, Asbury was previously booming with activities, ferris wheels, games, etc. There was even once a horse track where there is now a parking lot.

CONCLUSION

While the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection focuses closely on the late 19th through mid-20th centuries, it is also relevant to a variety of timely topics. Because of this, its postcard series is a great place to start research on the Asbury Park, leisure, East Coast culture and development, and visual culture. There are, at the very least, enough images to acquaint a researcher to the area and its specific civic importance. At the other end, the series can provide insight into a large amount of research projects with a fairly wide scope. An example of its relevance is the way in which postcards pose as an interesting precursor to the visual culture we exist within today. In many ways, a postcard was the Instagram of people in the 19th century. The feelings that surround the purchase and sending of the postcard are similar to the reasons one takes photos of their vacation and travel spots today. Mailing the card has been replaced with posting on the internet and the back of the card has been replaced by the caption. In this way, postcards are also structurally similar to Instagram, balancing the impersonal nature of posting to a wide audience by allowing the image to have been captured by the individual. This, like postcards, provides a sense of community through sharing and receiving. However, it is not always to say “wish you were here,” but sometimes “look where I am.”

About

Rachel Ferrante is an undergraduate American Studies and Sociology student at Rutgers working at the Special Collections and University Archives through the Rutgers Public History Internship program. During Fall 2017, she processed the Helen-Chantal Pike Collection on Asbury Park, New Jersey. Outside of the library, she works on cultural history through research with the Aresty Program and in her papers.

To Learn More:

- Helen-Chantal Pike Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries

- City of Asbury Park

Works consulted:

- Nigro, Carmen. “Using Postcards For Local History Research.” New York Public Library Blog.

- Eastern Illinois University. “Postcards Research Guide.” Eastern Illinois University Resources.

- “History of Postcards.” Art History Archive Online.

All images displayed are postcards from the Helen Pike collection, Box 5, folder 1.

By Flora Boros

By Flora Boros