By Helene van Rossum

Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives has an unusual amount of Dutch materials among its collections. Readers of a previous post know that this is because of the close connection between Queen’s College (renamed Rutgers College in 1825) and the Dutch Reformed Church. As can be seen in our recently updated guide to Dutch manuscripts the majority of the documents relate to 18th century Dutch Reformed communities in New Jersey and New York.

One exception is a collection of 25 Dutch autographs that we recently found among the papers of John Romeyn Brodhead (1814-1873), author of the History of the state of New York (2 vols., 1853-1871). Stored in folders simply labeled “early Dutch documents” they turned out to be signed by famous Dutch naval commanders, statesmen, and members of the House of Orange, many of whom Dutch schoolchildren encounter when they learn about the Dutch “Golden Age.” During this period, roughly spanning the 17th century, the small, newly independent Dutch Republic became a maritime and economic world power, built a colonial empire, and played a major role in European coalition wars, while the political power in the confederation of seven provinces repeatedly shifted between the “State party” (the regents of the provinces of Holland and Zeeland) and the princes of Orange.

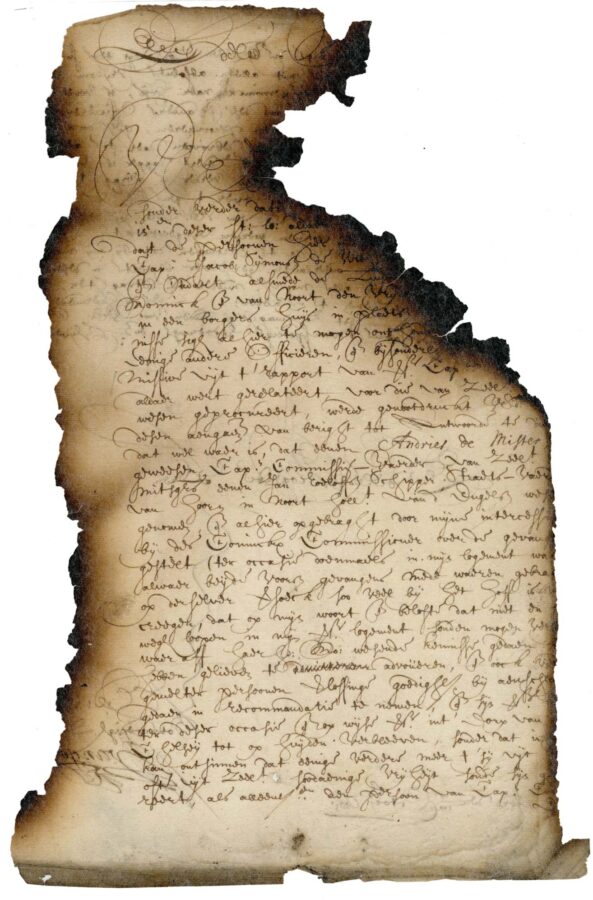

Among the autographs in the collection are signatures from Land’s Advocate Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt and his brother Cornelis de Witt (both lynched by an Orangist mob in the “disaster year” 1672) and the famous admirals Maarten Tromp and Michiel de Ruyter–the latter the subject of the 2015 movie Admiral. Most of the documents have extensive burn marks and were laminated decades ago with a fiber-like material no longer used by present-day conservators. How did these Dutch autographs, which should have been in the Dutch National Archives, end up among Brodhead’s papers? Why did they all relate to war ships or other naval matters? And why did most of them have burn marks? With the help of the Dutch historian Jaap Jacobs, who specializes in 17th-century Dutch and colonial history, we were able to unravel the mystery.

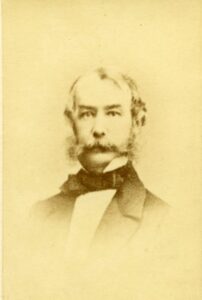

John Romeyn Brodhead (1814-1873)

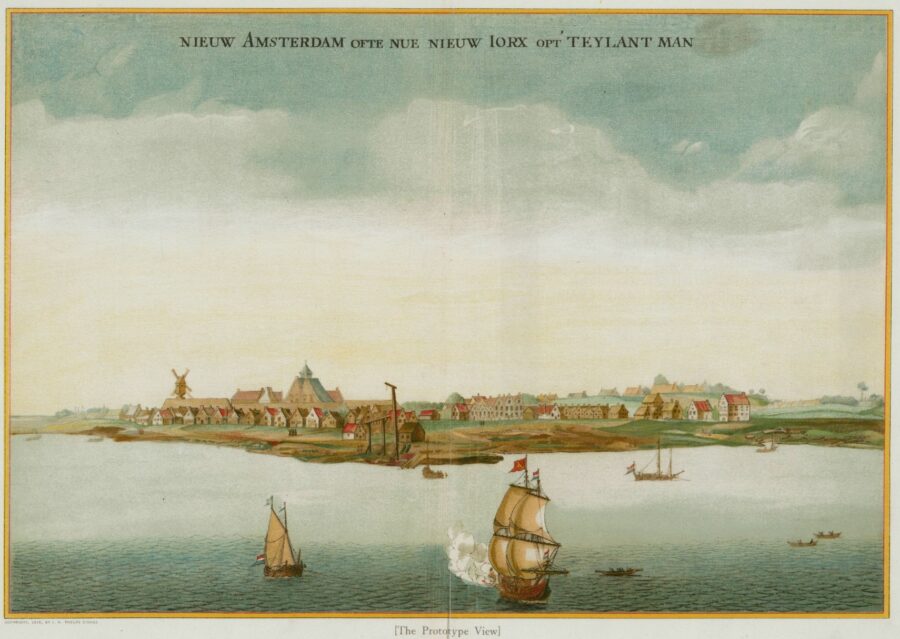

Brodhead was the son of a prominent clergyman of the Dutch Reformed Church and a descendent of one of the English conquerors of New Amsterdam in 1664, who settled with his family in Esopus, New York. John Romeyn Brodhead graduated from Rutgers in 1831 and was admitted to the bar in New York in 1835. Rather than pursuing a career in law, however, he devoted himself to the study of American colonial history. When he obtained an appointment as attaché to the American legation at The Hague in 1839, he scoured the Dutch archives for materials about the early Dutch history of New York. In 1841 he was appointed by New York governor William Seward to procure and transcribe documents in European archives concerning the colonial history of the state. In 1844 he returned from Europe with 80 volumes of transcriptions from Dutch, English, and French archives, which he listed in The Final Report in 1845.

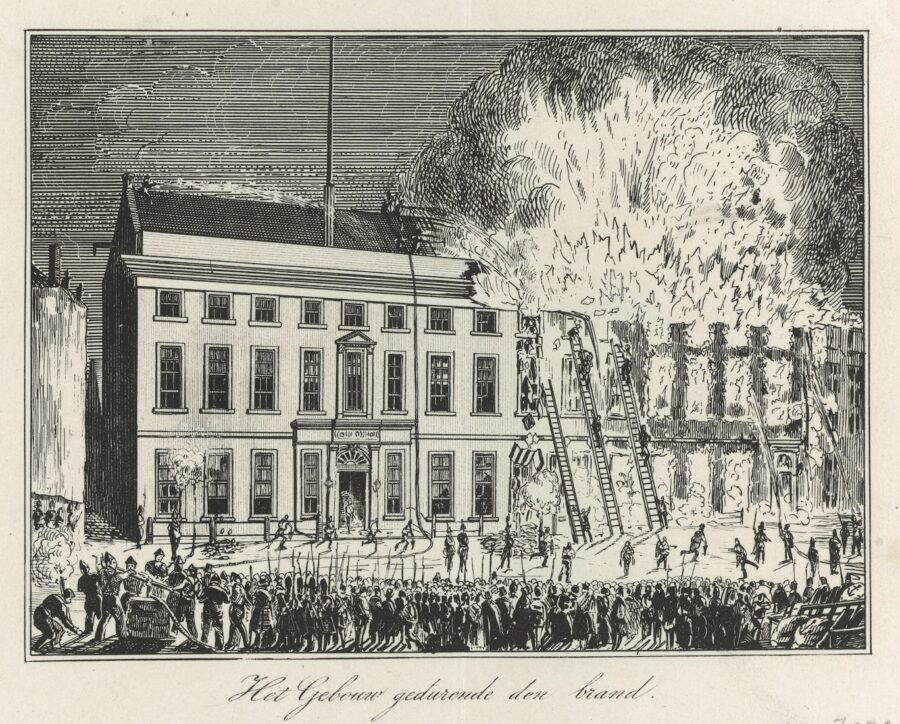

Fire at the Ministry of Naval Affairs, 1844

Familiar with Dutch history and 17th century handwriting, Brodhead must have easily recognized the names on the documents that we found among his papers. So how did he obtain them? Were they stolen? When we showed Jaap Jacobs the scorched documents, he was able to provide an explanation. At the time Brodhead visited European archives in the early 1840s, the archives of the five Dutch admiralties, which administered naval matters in the Dutch Republic, were held at the “Ministerie van Marine” (Ministry of Naval Affairs) in The Hague. On January 8, 1844, a huge fire broke out in the building, when a maid lighting a candle in the minister’s quarters accidentally set the curtains on fire. The quickly spreading fire is described in detail in a pamphlet with folded-out images of the building before, during, and after the fire. To save the archives, people threw the smoldering papers out the window, but the blazing wind spread them across the city in the sleet and snow. According to the finding aid to the Admiralty Archives in the National Archives only part of the materials was returned: these can be viewed (with similar burn marks) under their respective folder-level descriptions (see example). Many ended up in the hand of collectors such as Brodhead.

Paperwork during a naval war

Although the people who signed the documents were important historical figures, the contents themselves relate to less significant matters. The 1613 letters from Johan van Oldenbarneveldt, for instance, who had played a major role in the Dutch Republic’s struggle for independence but was beheaded for “treason” in 1619, merely concerned getting somebody a job, and providing a ship for a captain to carry certain letters. As a whole, however, the documents provide a fascinating glimpse of the day-to-day administration of running the navy, at a time when the country protected merchant ships and engaged in warfare during the Eighty Years’ War against Spain (concluded in 1648), the first three Anglo-Dutch wars (1652-1674) and the Franco-Dutch war (1672-1678). The letters to the admiralties address a wide variety of practical issues: from the provision of safe passage of foreign ambassadors, to naval blockades, smugglers, and, as in the letter displayed above, Dutch sailors who were captured at sea and required intercession from the Dutch ambassador at the English court (in 1665 temporarily residing at Oxford to evade the plague in London).

(Read descriptions on page 5-8 of the list).

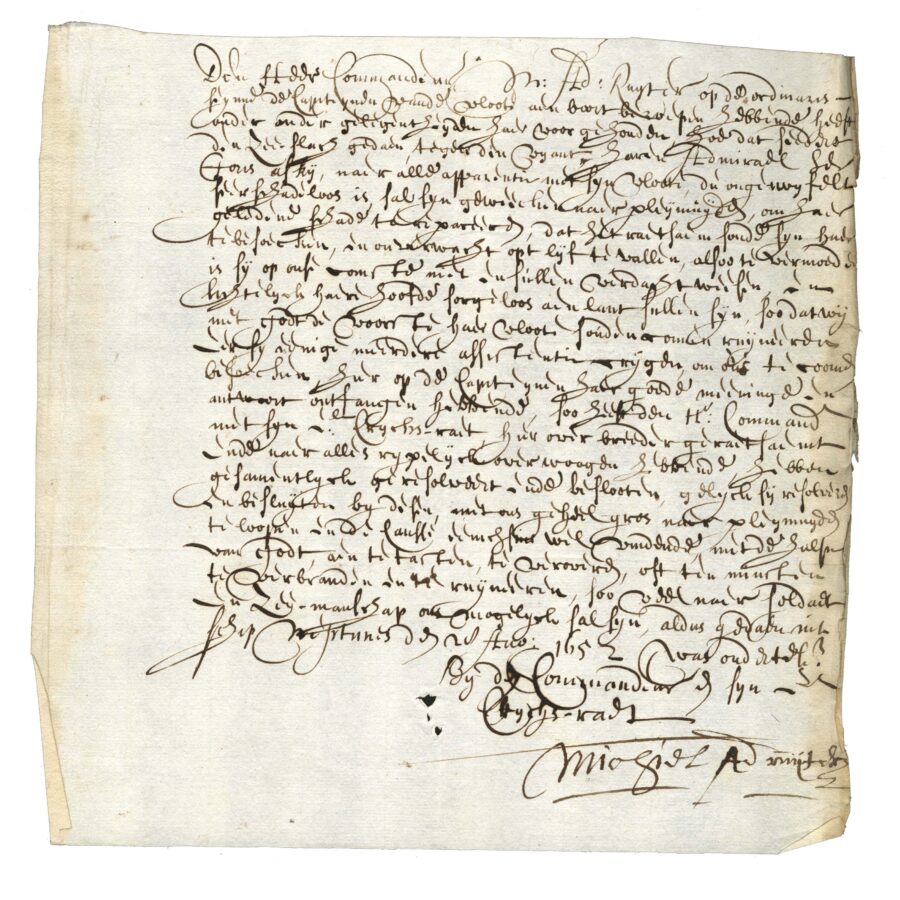

The most interesting letters are those from Dutch admirals who report to their employers about their commissions, detailing their travels, who they met, and the weather. The letters include requests for new orders and supplies and sometimes complaints, such as in the case of Vice-Admiral Johan de Liefde, who reported about ‘stinking beer’ (1665). The greatest surprise was an undamaged resolution by Michiel de Ruyter and his Council of War aboard the ship “De Neptunis,” two days after the battle of Plymouth on August 26, 1652 (August 16 according to the English calendar). During this early battle in the first Anglo-Dutch war, General-at-Sea George Ayscue attacked a Dutch convoy of 60 merchant ships sailing to the Mediterranean, escorted by De Ruyter’s squadron. Although the English fleet had more ships and was better armed, De Ruyter won the battle and the English had to retreat to Plymouth for repairs.

The resolution by De Ruyter and his Council of War states that after long deliberations they had decided–when the circumstances would allow them and with the help of God–to “attack, capture, or at least burn and ruin the English fleet, as much as they were able as soldiers and sailors” (“aen te tasten, te veroveren, oft ten minsten te verbranden en te ruijneren, soo veel naer soldaet en zee-manschap ons mogelyck sal syn”). Historians know that De Ruyter very much wanted to go after Ayscue’s ships while they retreated for repairs (ultimately, the winds just did not work out in De Ruyter’s favor). But who would have thought it would be expressed in an official resolution, written on paper, and signed aboard the ship?

Disability pay for a sailor, 1781

Only one autograph in Brodhead’s collection dates from the 18th century, a time that historically is viewed less favorably than the glorious “Golden Age.” The Dutch themselves already considered the century as a time of decline, reaching its depths during the fateful 4th Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784), which England declared because of secret Dutch trade and negotiations with the American colonies. Discontented burghers, who called themselves “Patriots” and were inspired by the American Revolution, blamed Prince William V, Commander-in-Chief, for the inability of the fleet to protect Dutch merchant ships, as illustrated by the Battle of Dogger Bank, on August 5, 1781.

The autograph is a letter from Prince William V to the Admiralty of Amsterdam in support of a request by Johan Christoff Munsterman, a sailor who had lost his left arm during the Battle of Dogger Bank. Instead of the 350 guilders that were promised, Munsterman preferred to receive a silver ducat a week throughout his life–an early form of disability pay. Did the Amsterdam Admiralty grant this wish? Hopefully the answer can be found in the Admiralty Archives in the National Archives in The Hague. Thanks to modern technology, the documents in the Brodhead Collection are now digitized and virtually united with the other documents in the Admiralty Archives.

With greatest thanks to Jaap Jacobs for his help with the transcriptions and providing context for the documents