by Alexandra DeAngelis

With all campuses closed, students sent home from their dorms, classes migrated online, and the cancellation of commencement activities due to the global pandemic of COVID-19, 2020 is turning out to be a memorable year in Rutgers history. But this is not the first time Rutgers has endured hardships that have altered the ways students lived and learned on campus.

A little over a hundred years ago 1918 took Rutgers by storm.

By 1917 Europe was deep in the throes of World War I. On April 6th, 1917 the United States joined its allies Britain, France, and Russia, to fight on the battlefields in France. Back home in New Jersey, Rutgers was beginning to feel the changes brought on by the unresting war.

The 1917-1918 academic year saw a substantial reduction in attendance at Rutgers, as 67 men had already left college to join troops overseas at the end of the previous year.

At the start of the 1918 fall term, the total number of undergraduates had dropped from 513 to 286 undergraduate students. Now, over 200 men were enlisted in the War effort.

Rutgers became a part of the War Department’s Students Army Training Corps (SATC), which prepared men from Rutgers and other institutions, including Princeton and Harvard, to be trained for officers’ positions with the directive that in a few month’s time they would take their places in the command of companies stationed in the fight abroad. (William Henry Steele Demarest, A History of Rutgers College, 1766-1924 (New Brunswick: Rutgers College, 1924, 536-38.)

The SATC instituted a new order of college life. Dormitories and fraternity houses were outfitted barrack style to house the men. Military regulations overtook daily activities, instruction in military procedure and training took the place of normal college life. Though studies were reconfigured to fit within the regime of military training, the usual curriculum was largely sustained. (ibid.)

A formal ceremony was held on October 1, 1918 instituting the SATC and swearing in about 400 college men as soldiers of the United States.

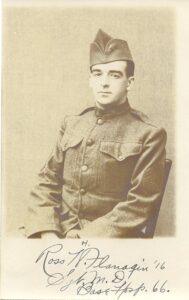

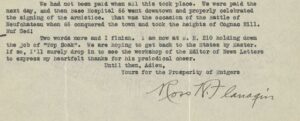

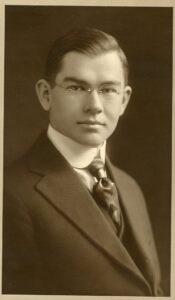

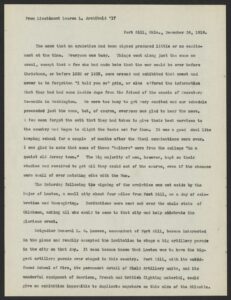

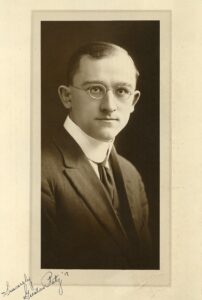

To maintain contact with Rutgers men fighting abroad, President William H.S. Demarest and assistant Earl Reed Silvers, “Sil”, implemented the War Service Bureau of Rutgers College in August of 1917 with the aim to keep Rutgers alumni in contact with the college and each other during the war. As acting director of the Bureau, Silvers sent letters to Rutgers men serving in the armed forces, soliciting responses about the experiences in the service. Silvers also sent out issues of Rutgers Alumni Quarterly and notified Rutgers alumni of government job openings. The Bureau resulted in a collection of over four thousand letters documenting the experience of Rutgers alumni during World War I (http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/ead/uarchives/warservicebureauf.html).

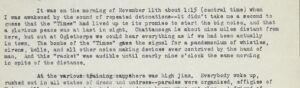

This adjustment to normal college life was not long lasting. On November 11, the armistice was signed. Shortly after, the SATC was disbanded and student soldiers were discharged on December 14. (Demarest, A History, 539)

Rutgers felt the effects of the disturbances of war for a year or two after the student soldiers returned. Many men took a long time to return to attain credits for a degree. Undergraduates who were active in the service received half a year’s credit towards a degree upon their return to their studies. Some, however, never returned. (ibid.)

After this brief period of disruption in the fall of 1918, Rutgers was prepared to return to the regular curriculum, but the semester found itself marked again by the epidemic influenza, known as the “Spanish Flu,” “the grippe,” “Spanish Influe,” and “the bug.”

The influenza of 1918 ranked as one of the deadliest epidemics in history- exacting a higher toll in a year than in four years of the Black Death or the Bubonic Plague. Between spring of 1918 and winter of 1919, the influenza killed as many as one in every eighteen people.

One theory is that the influenza began in Haskell County Kansas. An outbreak in the county was recorded in January 1918. The direct cause of the influenza is still unknown, although two potential influences have been identified: Haskell County was a prevalent hog farming community. The county also sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards. “Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus.” (John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” National Geographic (November 2017), accessed April 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/.)

The first reported cases of the influenza virus were documented in Haskell County. Haskell men who had been exposed to the virus went to Camp Funston in central Kansas to train for World War I. Within two weeks, 1,000 soldiers from the camp were admitted to the hospital, while many remained sick in the barracks. Thirty eight men from Camp Funston died. It is believed that infected soldiers from Funston transmitted the virus to other Army camps across the United States; out of the 36 US camps, 24 reported outbreaks. The soldiers continued to spread the virus across the nation and eventually overseas at their arrival in France. (Barry)

At the height of America’s involvement in World War I, between September and November 1918, nearly 40 percent of American servicemen were infected. (“Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken!”, 23)

The influenza was dubbed the Spanish Flu, not because it originated in Spain, but because Spain was a neutral country during the War. While the Allied and Central Powers suppressed any mention of the influenza in the news as to not weaken morale, the Spanish press freely reported on its progression. Many other countries underwent a media blackout, so their only sources of detailed information came from the Spanish media. This led to the assumption that the influenza began in Spain. In Spain, however, believed the virus had come to them from France (which may be partially true given the American Army’s stations in France), and they called it the “French Flu.” (Evan Andrews. “Why was it Called the ‘Spanish Flu’?” History, January 12, 2016, https://www.history.com/news/why-was-it-called-the-spanish-flu)

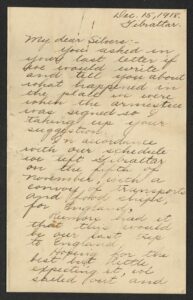

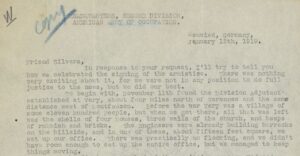

Even those spared the influenza during the war in Europe were not free on their return to the United States. Elmer. G Bracher, stationed at a convalescent camp in France wrote to Earl Reed Silvers as part of Rutgers’ War Service Bureau. In one letter from 1918, Bracher expresses the “hard luck” about a mutual acquaintance, Jill Jackson. Despite all the chances of catching some infectious disease while serving aboard, Jackson had returned home unscathed, only to catch “the ‘flu’” upon arriving home. (https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/52450/JPEG/read/#page/46/mode/2up)

Indeed, the influenza of 1918 was the most serious and wide-spread sickness the student body of America had ever known. It affected almost all colleges and universities, some experienced large numbers of student illness and death. William H.S. Demarest, President of Rutgers College from 1906-1924, only includes a small mention of the influenza in his 1924 book, A History of Rutgers College, 1766-1924. Demarest reports that only about seventy-five students fell ill from the influenza in the fall of 1918, all at various points in time. Despite these low numbers, Rutgers responded to the epidemic by transforming the Ivy Club (“Fraternity Houses Being Used,” The Targum, October 23, 1918, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/74/mode/2up.) into an infirmary where one student died. (Demarest, A History, 539) Three other Rutgers students died in their homes. (Demarest, A History, 539)

Various campus activities were cancelled due to the influenza. Rutgers was set for a football match against Lafayette College on October 12, 1918. Earlier that week, there was an outbreak of the influenza at Lafayette and the college went into quarantine, ceasing all athletic activities. (“Lafayette Game Cancelled,” The Targum, October 9, 1918, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/42/mode/2up.)

The newly opened New Jersey College for Women (later Douglass College) was forced to close less than a month after welcoming students, due to an outbreak of the influenza that had made victims of “the Dean and nearly half of the student body.” (“Spanish Influenza,” The Targum, October 16, 1918, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/60/mode/2up) The college reopened its doors on October 21st, just two weeks after shutting down. Students embraced their arrival with a welcome party. (“Women’s College Reopens With 51 Students,” The Targum, October 30, 1918, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/90/mode/2up.)

On October 16th, 1918 Rutgers published an article in The Targum advising students on how to best weather the storm of the influenza. Their advice for preventing the spread of the 1918 influenza are similar to the practices we must follow in the wake of COVID-19, including covering mouths when you cough or sneeze (though The Targum suggests one should cover their mouth with their ubiquitous handkerchief. We’d be hard pressed to find a student who carries a handkerchief today! Maybe we should bring them back?) and to avoid contact with anyone with symptoms including, fever, sneezing, a bad cough or cold, sore throat, pain in the chest, or general weakness or chills. Most importantly, the article in The Targum reminds students to limit their time spent in crowds– social distancing 1.0! The article asserts that “if we all observe these precautions, the epidemic will soon be a thing of the past.” (“Spanish Influenza.”) A student’s poem submitted to the “Targumdrops” section of The Targum provided a bit of levity during this hard time:

I now must write a line or two,

As all good poets sometimes do.

Of all sickness, I am glad

“Influ” I have never had.

I never mind a chimney “flue,”

Or an army cot, just broke in two;

But of all the birds that ever fly,

This “flu” bird simply takes my eye.

So take a bath, and never doubt

The “flu” will get you,

If you don’t watch out.

(Poem from “Targumdrops,” The Targum, October 30, 1918, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/92/mode/2up.)

Rutgers University has weathered many storms over the 250+ years of its existence. The bonds of Rutgers’s students, faculty, staff, and alumni have never wavered and times of disruption have only made us stronger. Undoubtedly, the year 2020 will go down in the annals of Rutgers history. We must keep the enduring spirit of our Rutgers predecessors in mind as we continue to adjust to learning and living away from campus and remember that as Rutgers has persevered through the hardships of war and influenza, we too shall forge our way through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Works Cited:

Andrews, Evan. “Why was it Called the ‘Spanish Flu’?” History. January 12, 2016. https://www.history.com/news/why-was-it-called-the-spanish-flu.

Barry, John M. “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America.” National Geographic. November 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/.

Bracher, Elmer G. Letter to Earl Reed Silvers. December 1918. Box 9, Folder 5, RG 33/C0/01 Records of the Rutgers College War Service Bureau. Special Collections & University Archives, Rutgers University Archives.

Demarest, William Henry Steele. A History of Rutgers College, 1766-1924. New Brunswick: Rutgers College, 1924.

“Fraternity Houses Being Used.” The Targum. October 23, 1918. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/74/mode/2up.

“Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken!”: New Jersey in the Great War. 2017. Special Collections & University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

“Lafayette Game Cancelled.” The Targum. October 9, 1918. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/42/mode/2up

Poem from “Targumdrops.” The Targum. October 30 , 1918. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/92/mode/2up.

Records of the Rutgers College War Service Bureau. RG 33/C0/01. University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

“Spanish Influenza.” The Targum. October 16, 1918. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/60/mode/2up.

“Women’s College Reopens With 51 Students.” The Targum. October 30, 1918. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/63506/JPEG/read/#page/90/mode/2up.