By Helene van Rossum

Helene van Rossum is a Dutch-born researcher and writer, who worked at SCUA as public services and outreach archivist from 2016-2018

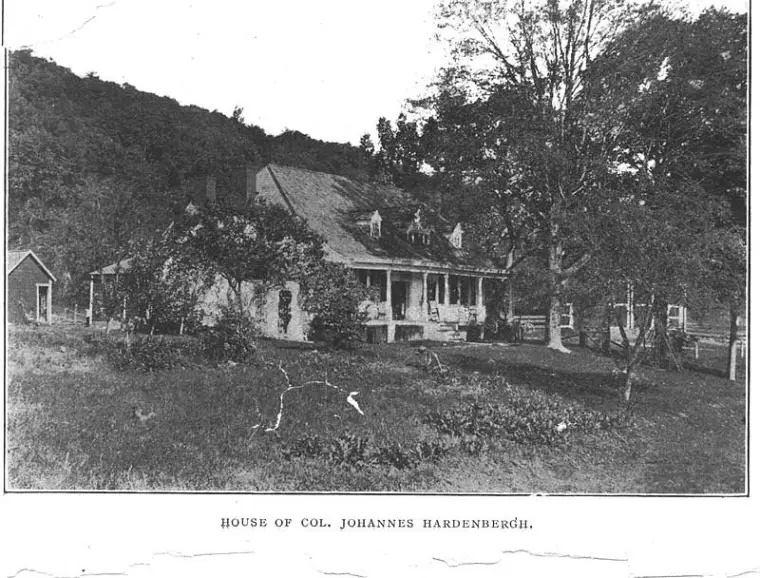

In our previous blog post we talked about the death of Johannes Frelinghuysen, Dutch minister in the Raritan Valley, and about his widow Dina van Bergh, who married Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh from Ulster County, NY. In this post we will follow up with Johannes’ three younger brothers, two of them called by Ulster parishes to be their minister. Their fate played a role in a schism in the Dutch Reformed Church in the American colonies between the “Coetus” and the “Conferentie” factions, and therefore ultimately in the establishment of Queen’s (later Rutgers) College.

Perished at sea: Jacobus and Ferdinandus

When Johannes Frelinghuysen died of a sudden illness in September 1754 on his way to an annual meeting of the Coetus, the ecclesiastical body was no more than an assembly of ministers and elders representing their congregations. But its position and function would soon be subject of a sixteen-year-long battle. As explained by former Rutgers University Archivist Tom Frusciano, the lack of authority within the churches to educate, examine, and ordain had become a pressing concern among ministers and congregations. While the numbers of churches had grown rapidly by the mid 18th century, there was a severe shortage of ministers to preach.

It was difficult to find Dutch ministers willing to move to the New World, like Johannes Frelinghuysen Sr. had done in 1720. For congregations it was a costly business to send a candidate to the Netherlands to be educated, licensed, and ordained. In addition, the journey was not only dangerous because of weather conditions, but also because of continuous warfare at sea. In 1745, on his way back after his ordination in Utrecht, Theodorus Frelinghuysen Jr. himself spent six additional months at sea because his ship had been captured by the French.

Despite these experiences, the Frelinghuysen brothers still favored the traditional way to get ministers licensed and ordained in the Netherlands.

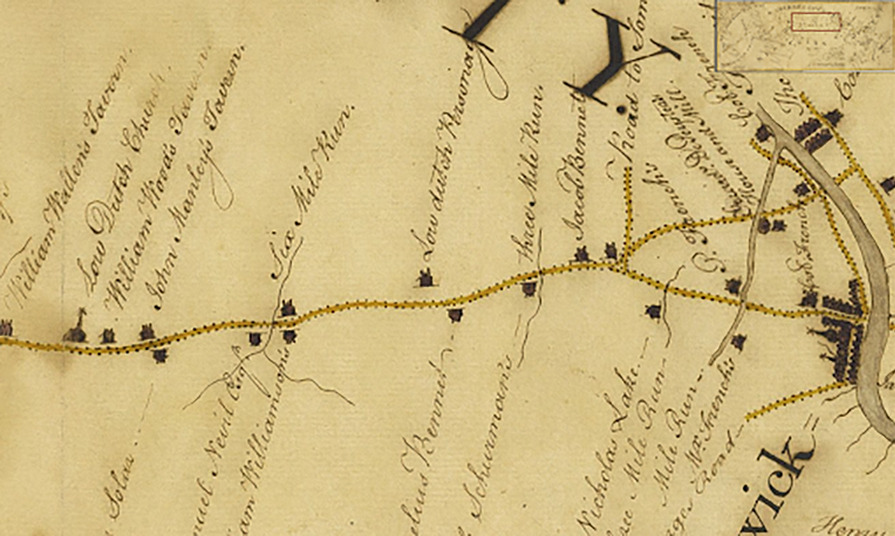

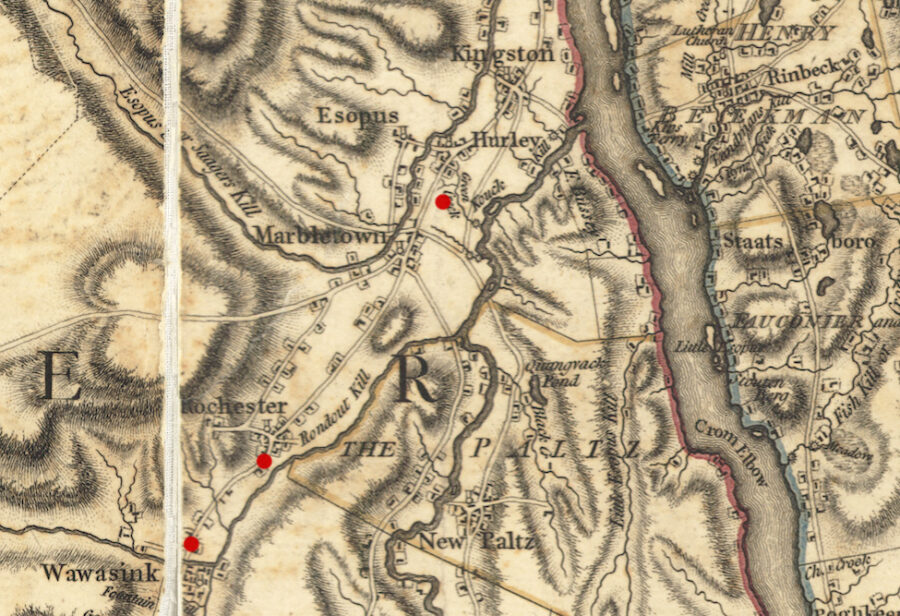

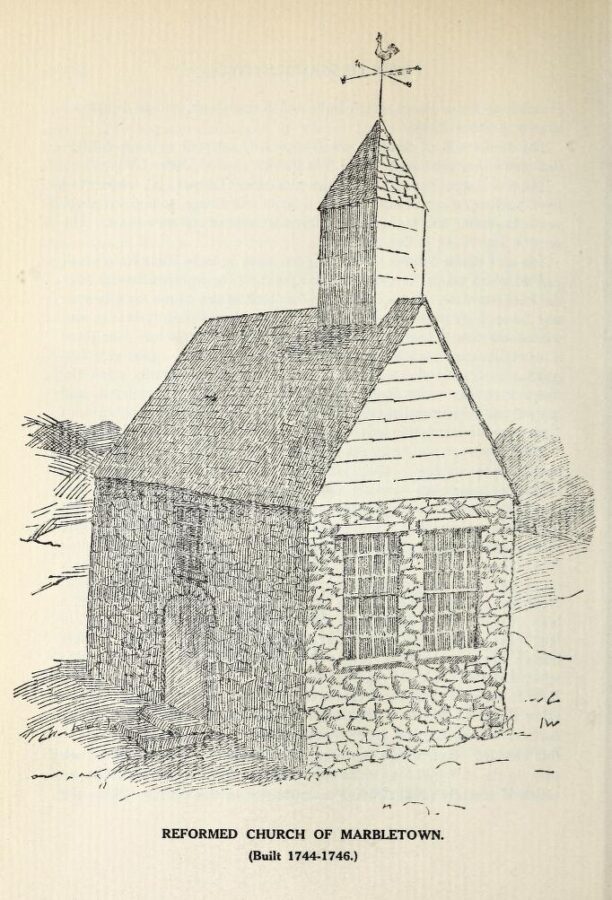

According to historian Dirk Mouw, “As late as 1751, when he assisted the congregations of Marbletown, Rochester, and Wawarsing, New York, in making out a call to his brother Jacobus, it was Theodorus Jr. who urged, and finally convinced those consistories, not to ask for examination and ordination in the colonies, but rather to permit Jacobus to go to Amsterdam for promotion.”1

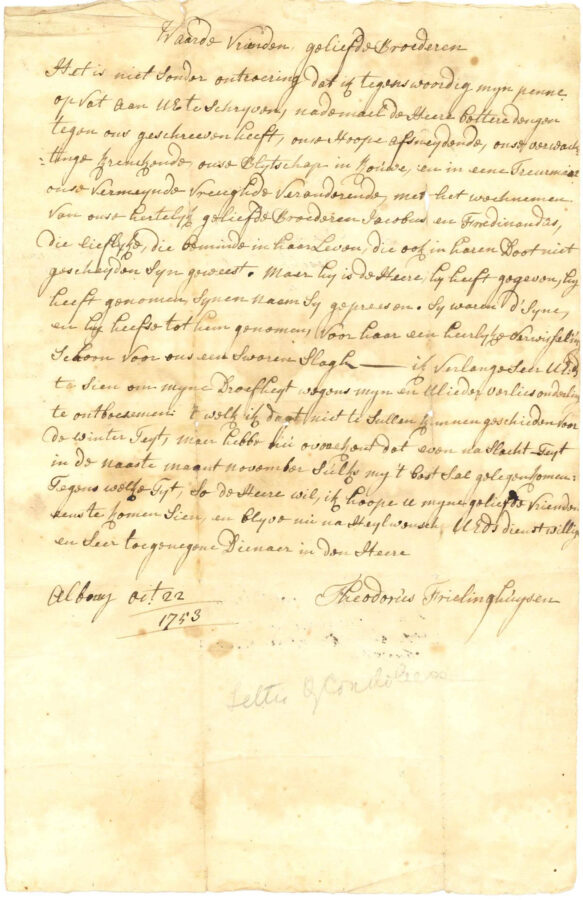

After Theodorus had convinced the three Ulster consistories to send Jacobus the young man and his brother Ferdinandus–who had been called to Kinderhook, 22 miles south of Albany, NY–left for the Netherlands. Sadly, when they sailed back two years later they both contracted smallpox and died in June, 1753, eight days apart. Though Theodorus notified the Classis in September 1753, it took him another month to be able to write the three Ulster consistories. The letter is kept at Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives along with other documents about the three Ulster congregations (view document list).

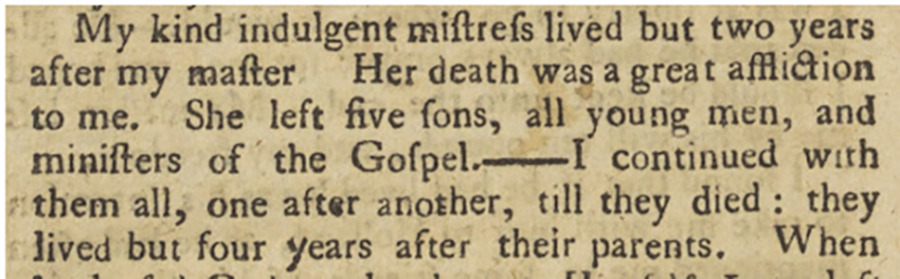

“It is not without emotion that I take up my pen to write to you presently, after the Lord prescribed us bitter things, cutting off our hopes, hurting our expectations, turning our happiness into coldness and our imagined joy into sadness, as he took away our dearly beloved brothers Jacobus and Ferdinandus, lovable and beloved in life, and unseparated even in death.

But he is the Lord: he has given, he has taken, praised be his name. They were his, he has taken them to himself, a glorious change for them, but a heavy blow for us.”

Battle for the Benjamin, Henricus

The death of the two Frelinghuysen brothers put new fuel on the smoldering fire. Soon after the news that their new minister had died, the congregations of Rochester, Marbletown, and Wawarsing decided to call the youngest brother, Henricus. Johannes Frelinghuysen in Raritan wrote to the Classis in August to ask for Henricus to be licensed and ordained by the Coetus.

“Not only has the loss of those two fine young men inflicted upon us a wound so severe, that we have the less courage now to let Henricus run the risk of the sea as well as other dangers; but he is the Benjamin in our family, and he has never had the smallpox. Churches have also already expressed their desire to have him as their minister. My humble request, therefore, of your Revs. is, that our Coetus may be authorized, upon evidence of his ability, to ordain him in the name of the Classis. Our case is an extraordinary one, and so there are extraordinary arguments for this request.”

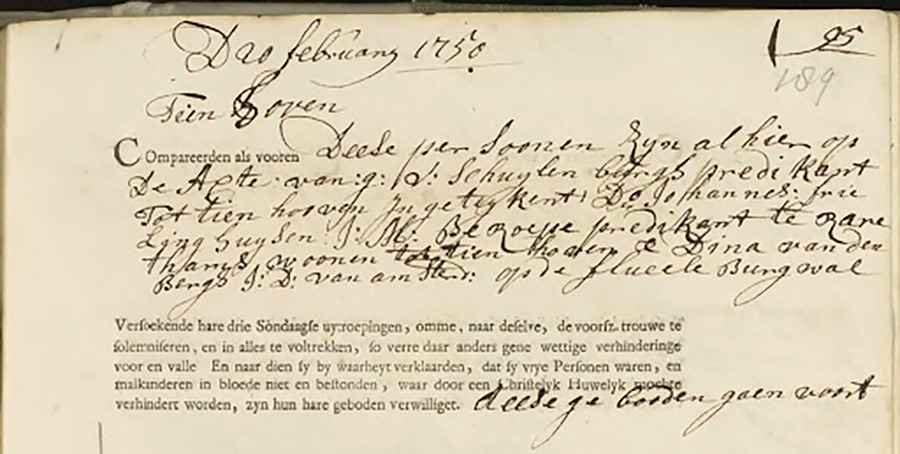

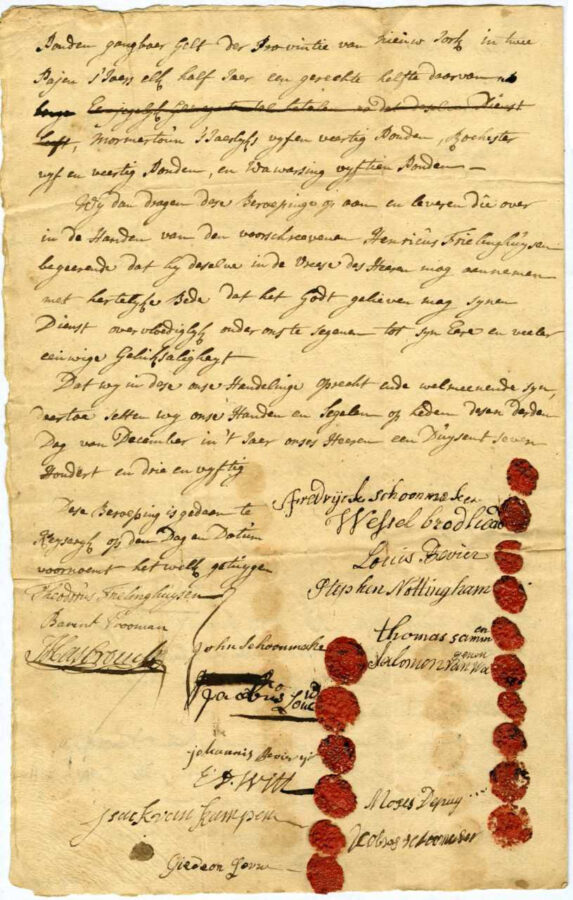

On November 3, 1753, the three Ulster consistories wrote the Classis of Amsterdam themselves. One month later, they sent Henricus a call, listing responsibilities and obligations on both sides. The Dutch letter with sixteen wax seals, which is translated in English, is also kept at Rutger Special Collections and University Archives.

The Coetus – Conferentie schism

In reply to his letter of August 1753 the Classis of Amsterdam wrote Johannes on May 6, 1754 that he should send Henricus over anyway. No doubt Johannes wanted to discuss the matter during the following Coetus meeting in September, but he died of a sudden illness on his way to Long Island. Nevertheless, during the three-day-long meeting it was decided to change the Coetus into a Classis, which, according to the minutes, would free congregations from the heavy expenses of sending their candidates overseas as well as the young men’s exposure to danger and the loss of time. An important additional reason was also provided: “Thus too we can prevent persons from seeking ordination from other communions differing from ourselves.”

Members of the Coetus soon found out that their president had organized an alternative, conservative, assembly, called the “Conferentie.” In addition, he negotiated behind their backs that the newly founded King’s College in New York (the future Columbia University) would have a professor in theology to teach prospective Dutch ministers. Though educated here, they would still have to be ordained by the Classis of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

In response Theodorus Jr. in Albany wrote the congregations a circular letter, calling for a meeting on May 23, 1755 to establish an American Classis and found their own American College. Thus started the schism in the church between the Coetus and the Conferentie Party, which would tear communities and families apart for the next sixteen years.

Henry dies too

Henricus was licensed by the Coetus in 1754, but he would not hold his position at Rochester, Marbletown, and Wawarsing for long. Only two weeks after his ordination by the Coetus in 1757, after the Amsterdam Classis had finally relented, he died of smallpox, like his brothers Jacobus and Ferdinandus before him. According to the Conferentie party in a letter to the Classis of Amsterdam Theodore Jr. defended his brother’s ordination during his funeral sermon and “sought to open the eyes of the people, saying that it was time to look away from the Classis.” One year later Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh from nearby “Rosendale” in Hurley would similarly be ordained by the Coetus to succeed their brother Johannes Frelinghuysen in the Raritan Valley in New Jersey.

You will find out about the sad fate of Theodore, the last remaining Frelinghuysen brother, in a following post by University Archivist Erika Gorder.

1 Mouw, Dirk Edward. “Moederkerk and Vaderland: Religion and Ethnic Identity in the Middle Colonies, 1690–1772.” Ph.D., The University of Iowa, 2009.

Part of the contents of this blog post were shared in the presentation “’That class of people called Low Dutch,’ African Enslavement Among the Dutch Reformed Churches of Ulster County and New Jersey’s Raritan Valley,” by Helene van Rossum and Wendy Harris at Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY (April 7, 2018).

With thanks to Wendy Harris.