By: Fernanda Perrone

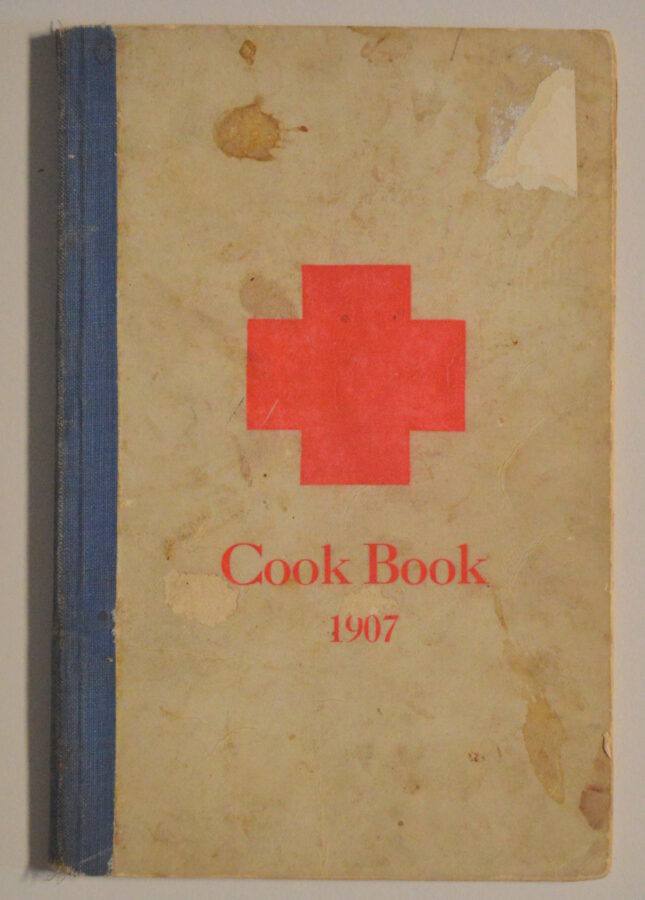

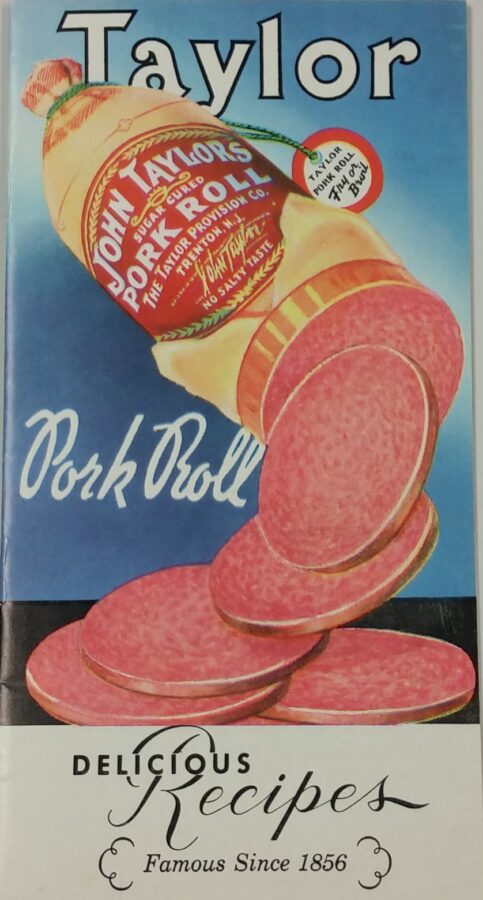

Many of the cookbooks on display in Special Collections and University Archives’ exhibition From Cooking Pot to Melting Pot: New Jersey’s Diverse Foodways contain recipes for Indian pudding.

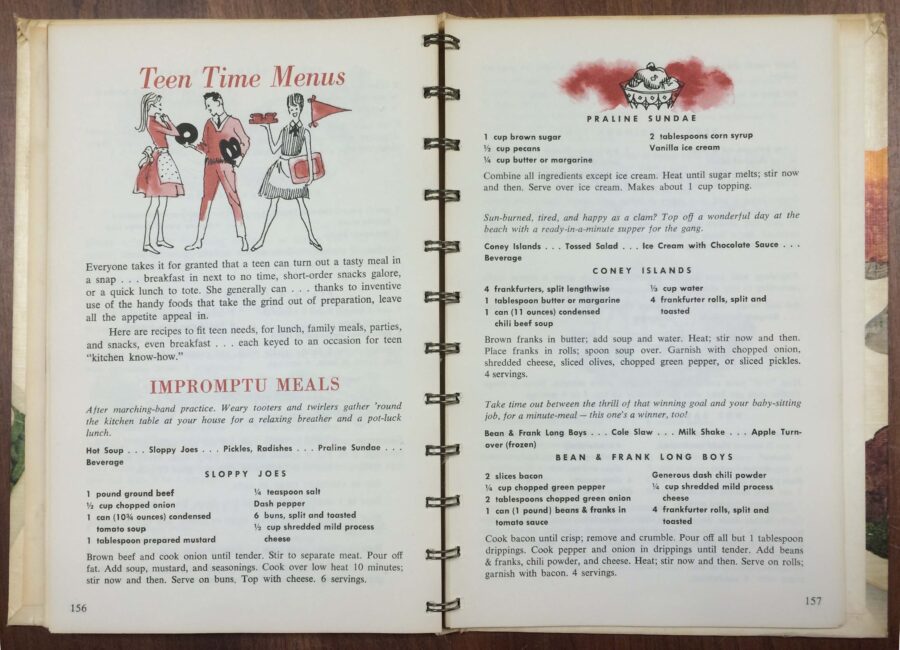

I had never heard of this dish, so I became curious about its history and thought I might even try to make it. Unlike my intrepid colleague Tara Maharjan, who has documented her efforts at historical baking on this blog, I used a contemporary recipe from the Joy of Cooking. In the spirit of the exhibit, I was interested in how recipes originally associated with particular groups had changed over the years, in some cases entering the mainstream.

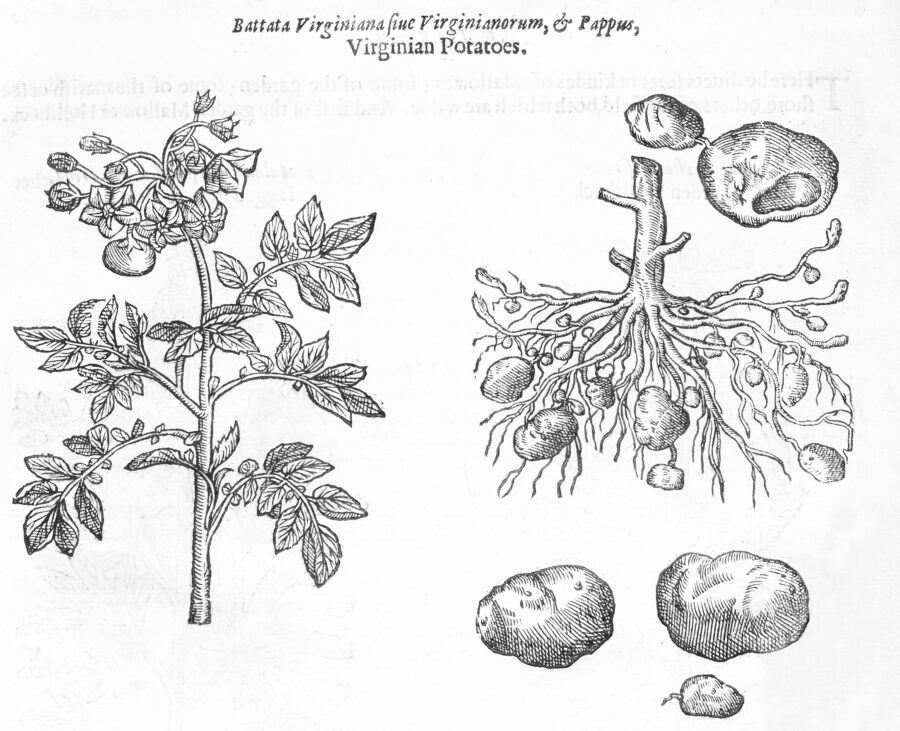

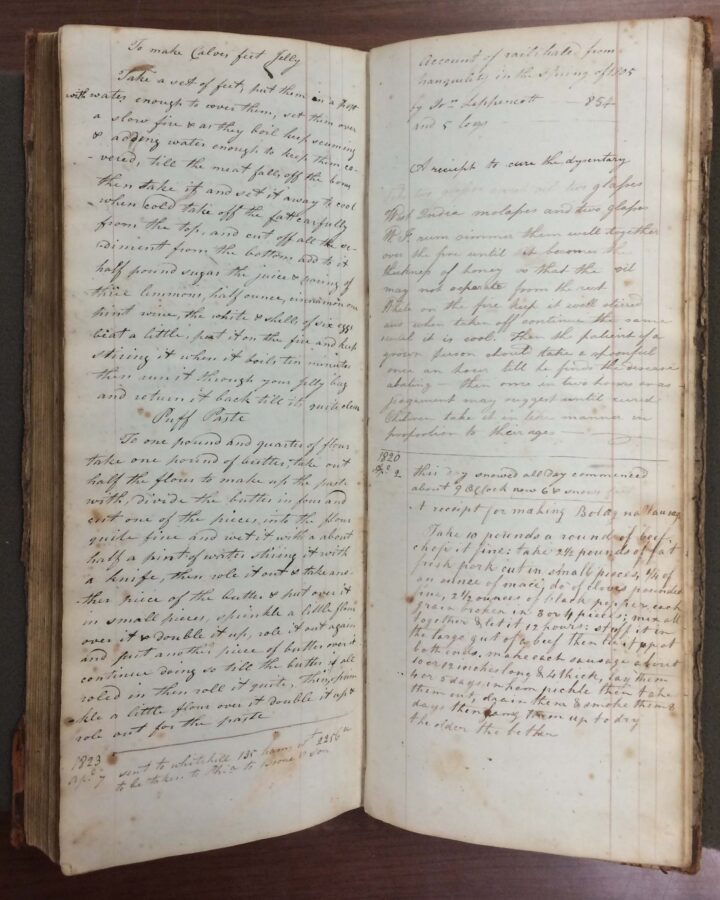

Indian pudding is a type of baked pudding, which are much firmer and more substantial than soft and creamy cornstarch puddings, because they include a significant amount of flour or other grain. Its main ingredients are milk, cornmeal, molasses, and spices. Indian pudding is a classic New England dessert, which, according to culinary lore, dates back to the Pilgrims. It may have its roots in British “hasty pudding,” made from boiling wheat flour in water and milk until it thickened into a porridge. In the American colonies, Europeans learned from Native peoples to substitute corn meal, which was indigenous in the New World, for wheat flour, thus giving birth to Indian pudding.

As in New England, Europeans in New Jersey learned about growing corn from Native Americans. The Lenape or Delaware Indians who lived in New Jersey were farmers, although they supplemented their diet by hunting and fishing. They grew over 12 kinds of corn. “Hard” corn was dried and pounded into cornmeal to make bread and other products. Corn and beans were staple crops, although they also cultivated squash, pumpkins, and tobacco. The Europeans who settled in New Jersey beginning in the mid 17th century included Swedes, Dutch, and Finns, Germans, and other ethnicities, although by the 18th century, settlers from the British Isles began to dominate. It is easy to imagine a settler cooking Indian pudding over an open fire.

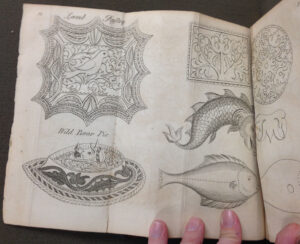

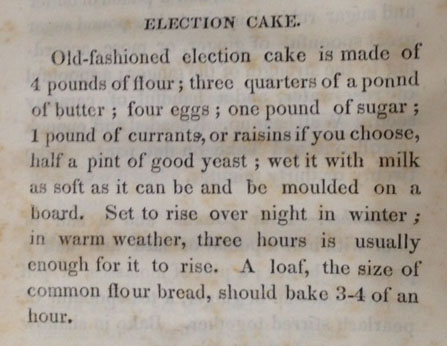

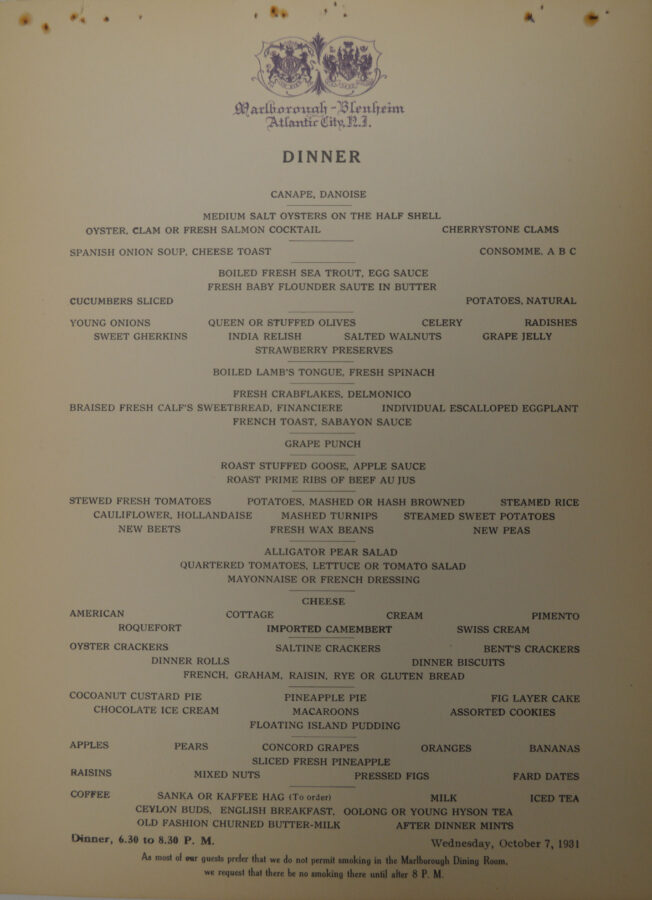

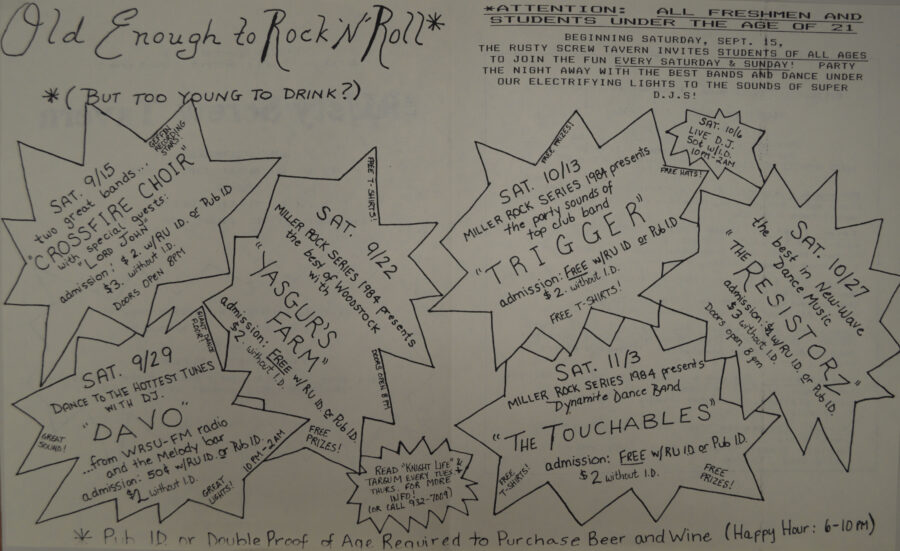

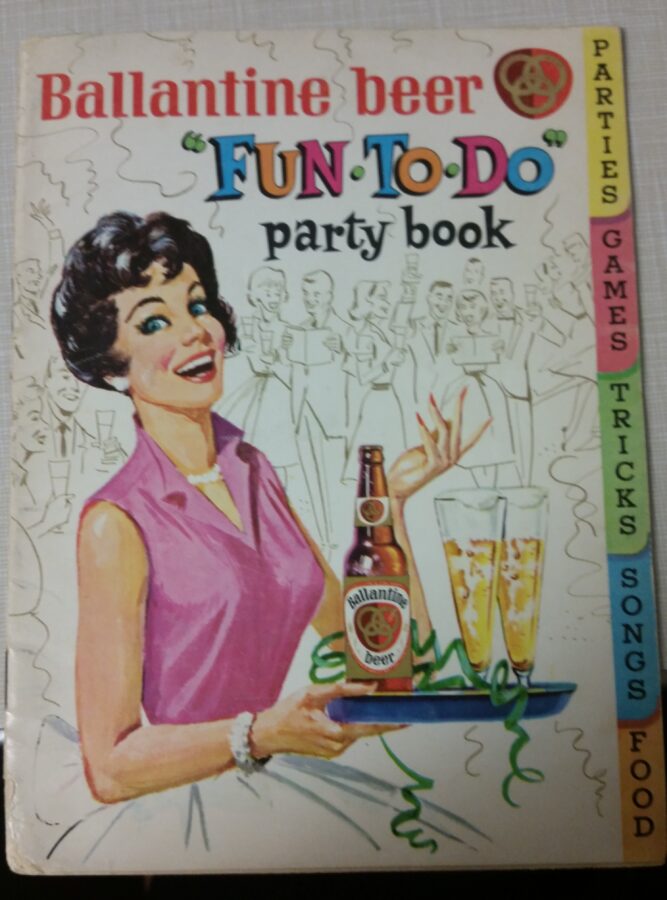

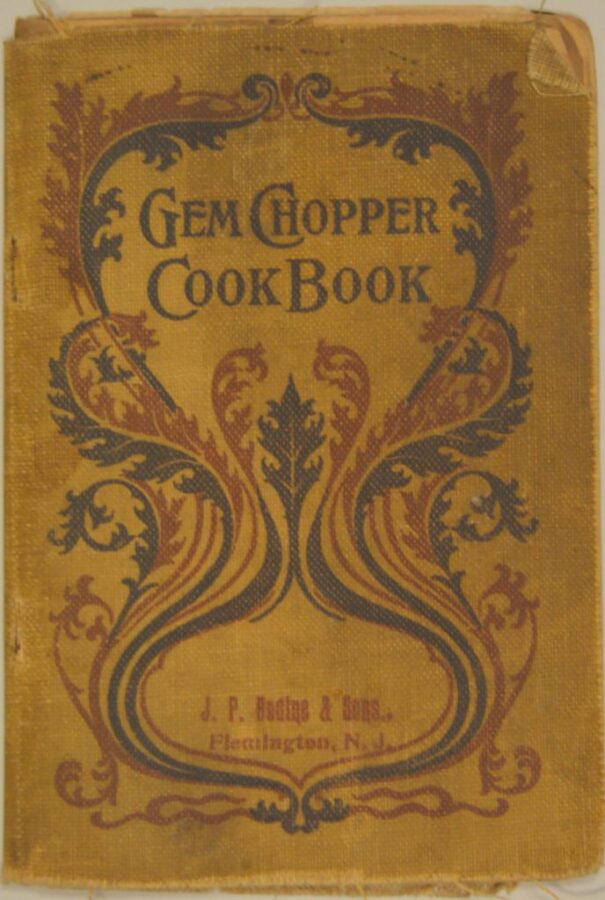

It is likely, however, that Indian pudding was a construct that emerged during the Colonial Revival of the late 19th and early 20th century. The centennial of the United States in 1876 brought forth new interest in the early history of the country. Most often associated with architecture, the Colonial Revival was also expressed through restaurant design, food advertising and the popularity of works like The Colonial Cook Book (1911). This cookbook included no less than five recipes for Indian pudding, along with recipes for baked beans, pies, and other supposedly colonial dishes. In Colonial Revival iconography, corn, the New World staple, became a symbol of national pride and patriotism through its association with America’s indigenous past. It also hearkened back to a time of mythical cooperation between Native Americans and Europeans, epitomized by the Thanksgiving Day feast, where Indian pudding was a frequent dessert.

Although Thanksgiving has past, this week’s cold weather seemed a perfect time to make Indian pudding. I felt the weight of culinary cultural imperialism on my shoulders as I assembled the ingredients, noting the depiction of a Native American on the package of Indian Head-brand cornmeal.

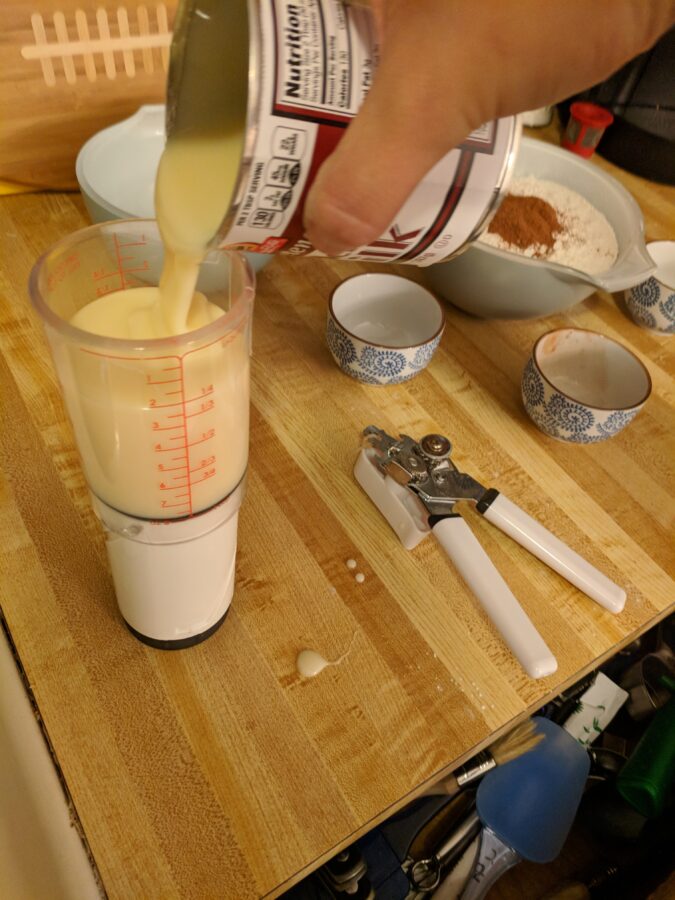

I mixed the cornmeal with the milk, realizing I was going to spend a considerable time standing in front of the stove stirring.

The mixture thickened nicely and I added the molasses, butter, sugar, salt, and spices. To my surprise, the pudding was supposed to bake for 2 ½ to 3 hours! I was glad I had started early.

After 2 ½ hours, the pudding had a brown crust on top and was bubbling alarmingly. I left it to sit for 45 minutes, and then served it with a little milk. The recipe suggested cream or vanilla ice cream. The pudding was still hot and had a delicious flavor of molasses and a smooth but hearty texture. It was enjoyed by all!

From Cooking Pot to Melting Pot: New Jersey’s Diverse Foodways will be on display in the Special Collections and University Archives Gallery through February 28, 2019.

References:

Carroll, Abigail. “’Colonial Custard’ and ‘Pilgrim Soup’: Culinary Nationalism and the Colonial Revival.” Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 2007.

“Indian Pudding,” A Family Feast, 2019 https://www.afamilyfeast.com/indian-pudding/

Lurie, Maxine N. and Richard Veit. New Jersey: A History of the Garden State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

Rombauer, Irma S. , Marion Rombauer Becker and Ethan Becker. Joy of Cooking. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Veit, Richard Francis and David Gerald Orr, ed. Historical Archaeology of the Delaware Valley, 1600–1850. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2014.