By Louise Lo Bello

The Ghost of Wallpaper’s Past

The other day I was strolling through the trails of Watchung Reservation when I stumbled upon the “Deserted Village”, a ghost-town deep in the woods of Watchung Reservation and currently maintained by the Union County Park System. The history of the village goes something like this: In the eighteenth century, Peter Willcocks settled on the area and used the land for his sawmill and farm which later turned into the print-making town of Feltville. In the late ninetheenth century, the skeleton of Feltville was transformed into a summer resort called Glenside Park. The tenement-like apartment buildings of Feltville were repurposed as luxury cabins for the resort and their wooden corpses still remain in the woods of Watchung Reservation.

In between smacking away mosquitoes, I tiptoed over the crumbling porch of one of Glenside Park’s converted cottages to get a closer look. I peered through a dusty window and managed to get a glimpse of the interior. As expected, there wasn’t much to see: An empty parlor with splintering floorboards, a central hearth with a paint-chipped, chalky white mantel, and my personal favorite, faded sage paisley wallpaper. A friend of mine commented, “I don’t believe in ghosts, but this place is definitely haunted.” A warranted response, but I envisioned what the cottage once was: A cozy place to return to for a few nineteeth century middle class vacationers after a long day out in nature. I laughed imagining how a rustic escape to the wilderness for Victorians still involved wearing long, heavy dresses and returning to a charming wallpapered cottage, sealed off from the elements. I kicked a mosquito off of my exposed left leg, smearing mud in the process.

I’ve been thinking about the solemn, cozy mood of that aging old parlor in the woods. What stood out to me most was the faded wallpaper that was completely torn off in spots and starting to peel in others, but for those who used the parlor over 100 years ago, it must have perfectly complimented the natural color palette of the outdoors. Nineteenth century design did not hold back from pattern and clutter and I expect that this aged wallpaper once played an important role in the overall experience of vacationing at the resort.

The Janeway Wallpaper Businesses: New Brunswick, NJ

A few months before my Deserted Village adventure, I received a reference inquiry at Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives from Bo Sullivan, antique wallpaper enthusiast and founder of Arcalus Period Design and Bolling & Co. He was working with a client who was in the process of renovating a historic house in Ohio. During the project, they came across remnants of antique wallpaper that was still stuck to the original wall. In a corner of the wallpaper it said “Janeway,” referring to a New Brunswick wallpaper company operating in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In an effort to restore the room to its original design, the renovation group and Bo contacted Rutgers SC/UA looking for wallpaper samples from Janeway & Carpender from the late 1800s, hoping to find a match. So I began my search. In the process, I developed a brief timeline of the Janeway wallpaper history of New Brunswick.

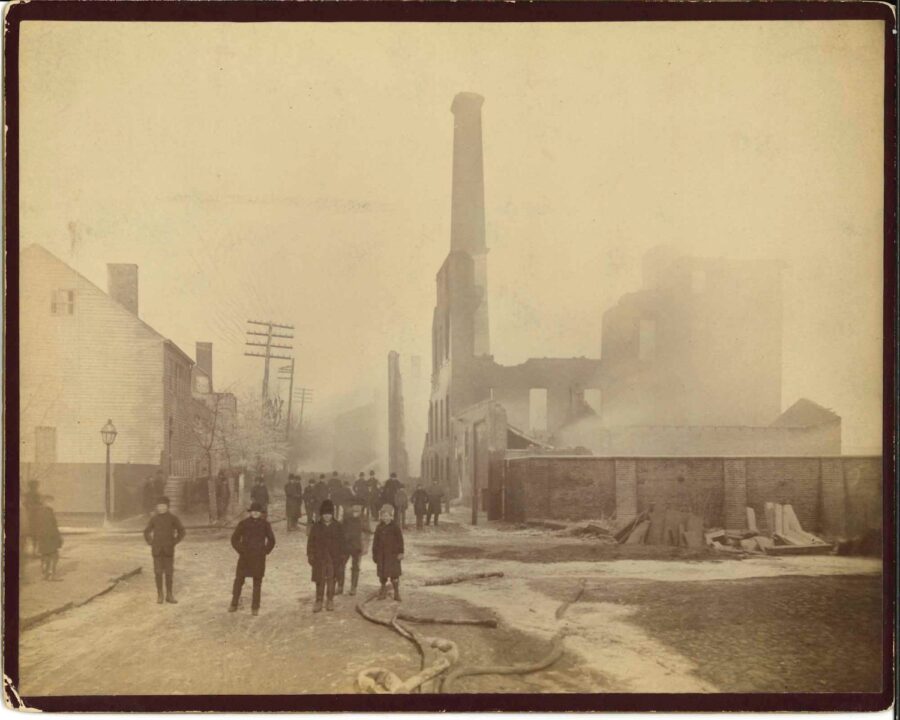

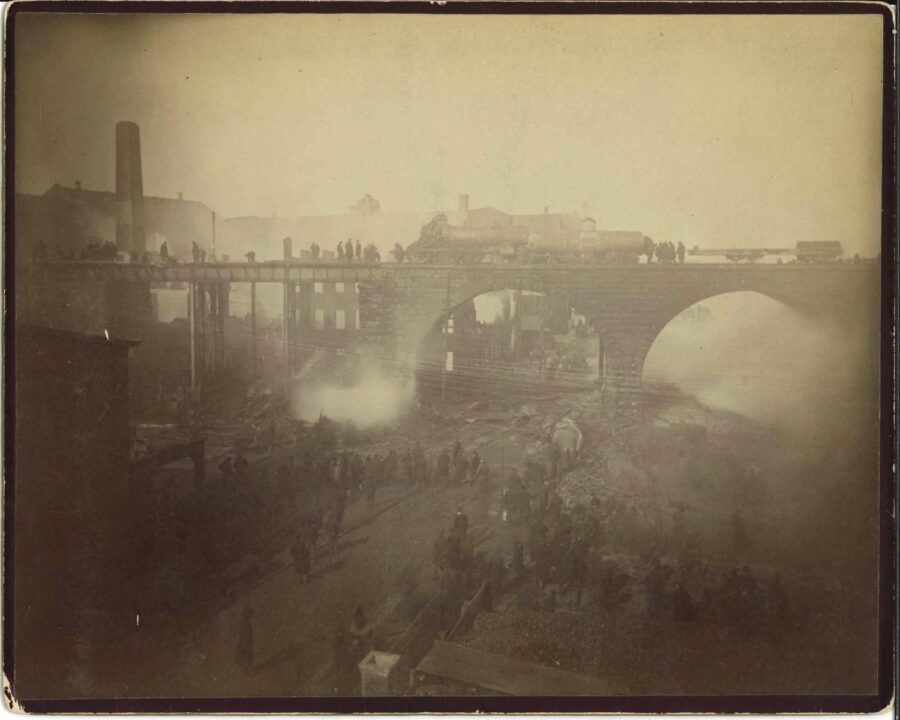

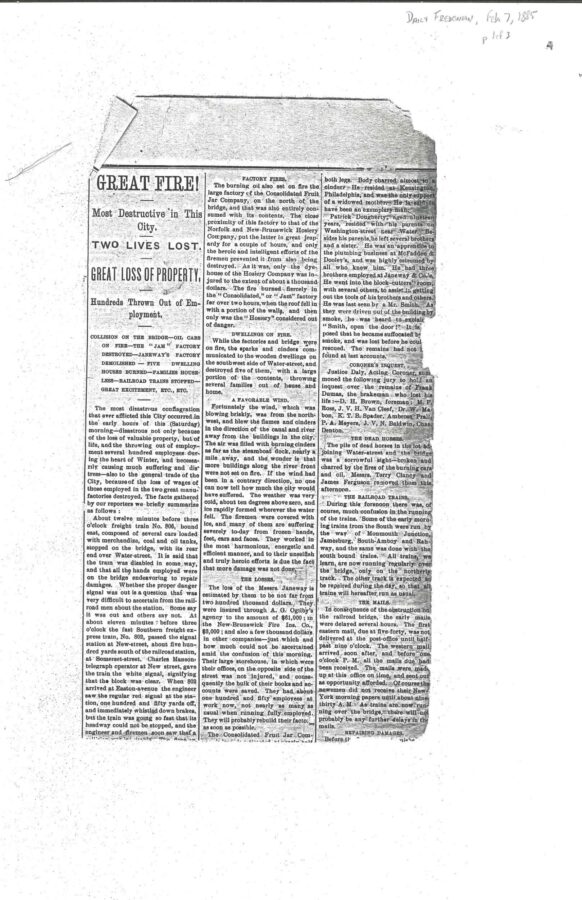

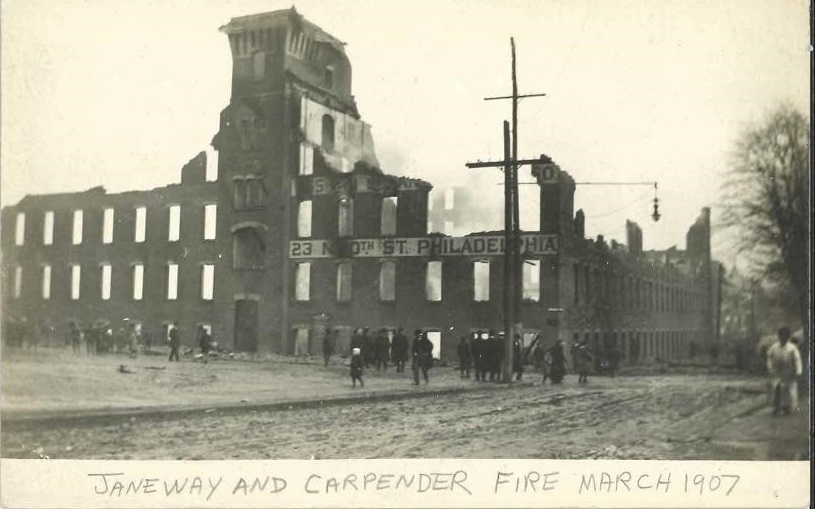

Janeway & Company, one of the oldest American wallpaper companies, was founded in 1844 and prospered until 1914 when William Janeway, head of the business, decided to retire. The factory was located on Water Street in New Brunswick, right along the Raritan River. In the early hours of February 7, 1885, two freight trains carrying oil collided on the bridge over Water Street. It ignited a series of fires in the area, including the Janeway & Company factory which was completely destroyed. The company eventually rebuilt and relocated to a stronger structure nearby. Jacob J. Janeway, of another branch of the Janeway family tree, worked at Janeway & Company from 1865 to 1872. He then partnered with Charles J. Carpender to develop Janeway & Carpender, based in New Brunswick. Jacob Janeway eventually bought out Carpender’s shares and the company continued to thrive well into the 1900s. Janeway & Carpender had factory buildings in the areas of Paterson, Schuyler, and Church Streets in New Brunswick and eventually expanded to Chicago and Philadelphia. They too, suffered the effects of a destructive electrical fire in 1907. Within two hours, the factory burned to the ground and for a year following, the site was reportedly still smoldering. The company built a new factory across the Raritan in Highland Park and at the time, it was the largest wallpaper wallpaper factory in the country.

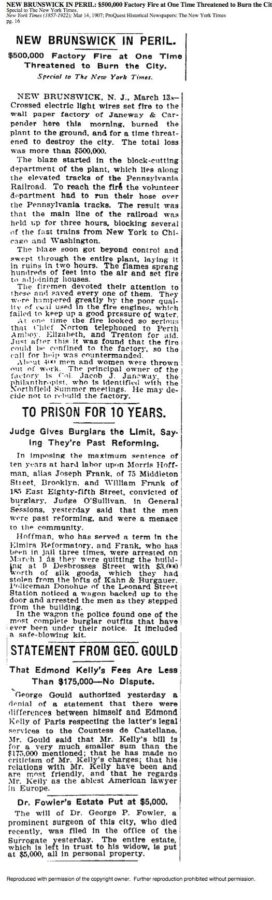

Newspaper clipping and photographs of the 1885 fire and the damage to Janeway & Co. factory (New Jersey Views and New Brunswick Vertical File):

Before and after the 1907 fire of Janeway & Carpender (New Jersey Views and New Brunswick Vertical File):

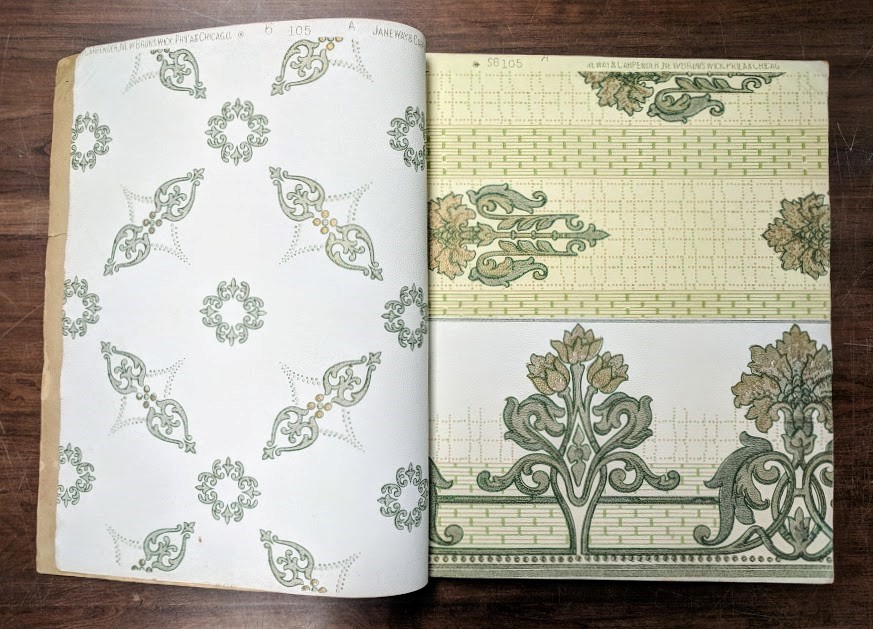

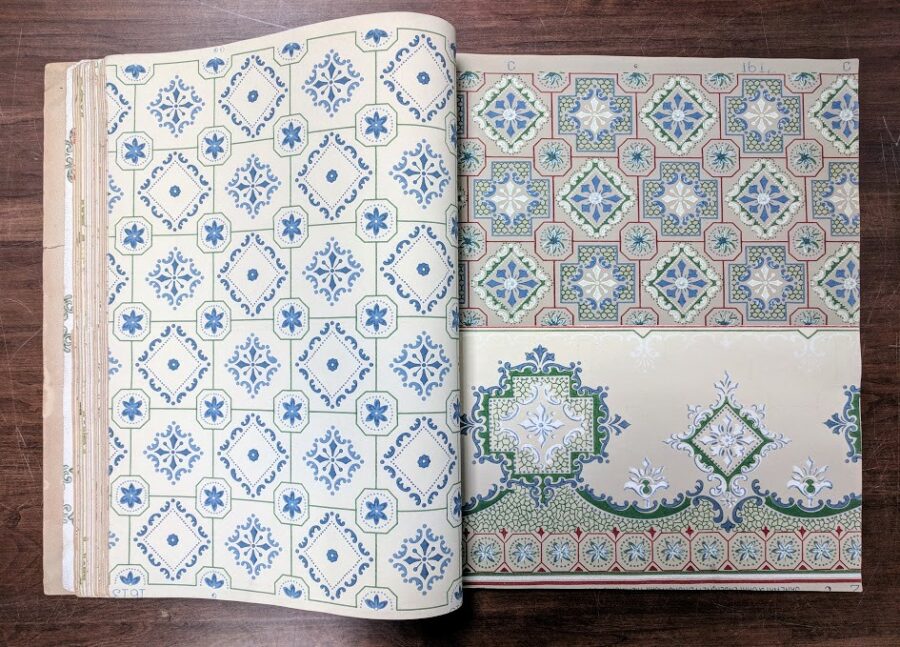

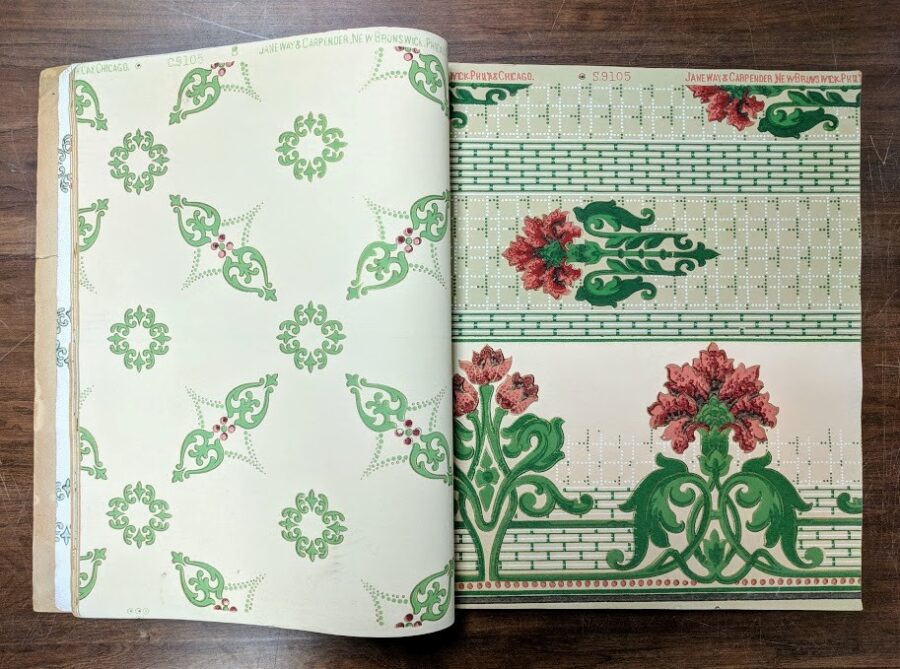

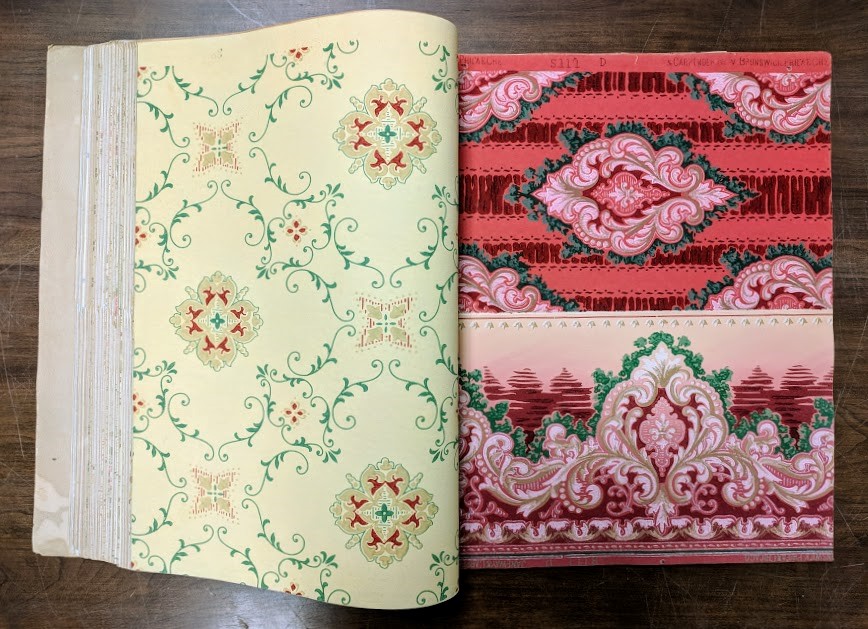

Wallpaper and Design

Amidst my research, I came across a few beautiful 1911 sample books from Janeway & Carpender in the Sinclair New Jersey Collection. They all include a trifecta of a border with coordinating backdrop wallpaper and ceiling pattern. The designs varied from page to page, but what stood out to me the most was the richness of the colors and the bold design. For example, some of the vibrant red and green patterns were shockingly intense. I questioned why nineteenth century folks sought for their rooms to look like Christmas just exploded all over their walls, but after awhile the Christmas-couture look started to grow on me. In fact, all of the pages were absolutely stunning. I thanked the wallpaper gods that they were not lost in a papery flame, since tragic fires seemed to be a trend for New Brunswick wallpaper factories.

Although the sample books in the collection unfortunately did not reveal a perfect match in design to the found samples in the historic house, they did pique my curiosity into nineteenth century wallpaper culture. What were the social implications of wallpaper? How did it compare to the other decorative arts during the period? And why is it no longer an interior design staple?

Prior to the early nineteenth century when wallpaper began to stick its patterned tendrils onto the walls of Western middle-class homes, it was not very popular. In contrast, Eastern countries had been using patterned rice paper as wall decoration for quite some time. In the West, wallpaper was generally associated with lack of wealth, imitation, and falsity. After all, if you intended to decorate your walls, why not go for a richly embroidered tapestry made of a fabulously expensive material? A true mark of high taste was the real, authentic thing and wallpaper was an imposter material, trying to be like its cooler, richer cousin. I can’t help but think of the tacky imitation-marble wallpaper that currently lines the bathroom walls of my family home and how it pathetically hangs off of the wall in places, like a child’s Halloween costume after a long night of trick-or-treating.

Prior to the early nineteenth century when wallpaper began to stick its patterned tendrils onto the walls of Western middle-class homes, it was not very popular. In contrast, Eastern countries had been using patterned rice paper as wall decoration for quite some time. In the West, wallpaper was generally associated with lack of wealth, imitation, and falsity. After all, if you intended to decorate your walls, why not go for a richly embroidered tapestry made of a fabulously expensive material? A true mark of high taste was the real, authentic thing and wallpaper was an imposter material, trying to be like its cooler, richer cousin. I can’t help but think of the tacky imitation-marble wallpaper that currently lines the bathroom walls of my family home and how it pathetically hangs off of the wall in places, like a child’s Halloween costume after a long night of trick-or-treating.

The Industrial Revolution gave rise to a fresh crop of laborers that operated new machinery. This led to an improved economy and a rising middle class in the mid-nineteenth century. As the economic classes became much less disparate, more people could acquire art and décor and experiment with interior design moreso than even before, igniting a consumerist boom. Additionally, the development of machine printing and a repealed tax on paper products allowed for folks to more readily choose to decorate their homes with wallpaper, a more affordable option than expensive fabrics and tapestries.

The Industrial Revolution gave rise to a fresh crop of laborers that operated new machinery. This led to an improved economy and a rising middle class in the mid-nineteenth century. As the economic classes became much less disparate, more people could acquire art and décor and experiment with interior design moreso than even before, igniting a consumerist boom. Additionally, the development of machine printing and a repealed tax on paper products allowed for folks to more readily choose to decorate their homes with wallpaper, a more affordable option than expensive fabrics and tapestries.

The Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts Movements in the latter half of the nineteenth century pushed back against industrialization and mass produced goods, emphasizing an “art for art’s sake” mentality. Designers like William Morris and C.F.A. Voysey were important figures in these movements, looking to non-Western countries and nature for design inspiration and abstracting traditional imagery into two-dimensional patterns. They also encouraged slower, handmade techniques of production such as block printing, as seen in Japanese prints. This non-Western influence also spurred collectors to purchase exotic pieces of furniture and other ornamental objects to decorate their homes.

The Deserted Village serves as a useful microcosm of the social and economic change over a few centuries of American history. Its humble beginnings as a farm and sawmill turned industrial factory town in the mid 1800s, and then, as if the spirit of William Morris himself breathed through the village, rebelled against the industrialized lifestyle and transformed into a summer resort, looking back to nature.

Less is (not always) more

Over the last century, the use of wallpaper has decreased in popularity. Design trends have shifted toward minimalism with white or neutral colored walls, glass panels, and a few quirky or “exotic” statement pieces. In my opinion, a general algorithm for any trendy interior includes whitewashed walls, an Eastern inspired tapestry (perhaps featuring a mandala or a hamsa) hanging loosely over a mid-century modern style sleek couch, complete with a lush green plant on the floor, for what I can only guess is to add some sign of life to the staleness of the space. I like to call this aesthetic the “blogger home”. Minimalism with a pop of color or texture and an interesting handmade basket from your most recent trip to South Africa makes for great Instagram content. In other words, it increases your social capital.

It is no new critique that a highly decorated Victorian household could be reflective of a colonizing worldview. Hand-picked trinkets and souvenirs from various countries and cultures were used to elevate one’s social status by appropriating them as their own. In many ways not much has changed in today’s design style. An interesting perspective on this whitewashed aesthetic is that it reflects something specifically tied to white-Americans. Young, professional hipsters are most often displayed in the media with quirkily decorated white-walled homes. Indeed, this style is not just centralized to American home design (the Scandinavians and Moroccans are just some of those who have been doing it for much longer), but there is still something to say about the bleaching of tonality and pattern, speckled with interesting trinkets to add a little “culture” to a home. In many ways, the only difference between some of today’s interiors and a Victorian interior is that the walls have now been scrubbed clean. Maybe we can learn something from the evolution of interior design, that evolution does not necessarily imply improvement.

Despite my criticism of this aesthetic, I acknowledge the benefits. White walls reflect light and help make a space look larger. They also allow for people to focus on beautiful objects and decorative pieces and allows them to move more easily without the risk of clashing with wall design. However, not all hope is lost on the wallpaper front as there seems to be a slow shift of reintroducing wallpaper into homes as accent walls. Rather than using it as a backdrop, wallpaper is now a point of focus in a room. And maybe this is what interior design needs. Nineteenth century wallpaper companies like Janeway & Carpender and designers like Morris and Voysey considered their product not merely as a cheap decorative backdrop, but as a work of art. Perhaps now, after the rise and fall of its popularity, the value of wallpaper can once again be elevated and provide a much needed element of mood and character to a room.

Where is our Glenside Park window into wallpaper history?

Looking to the design styles of the past can reveal a lot about the environment and people of a certain era. It is therefore important to maintain a record of the decorative arts, but wallpaper tends to present a preservation issue. Its very nature is ephemeral, discrete enough to be painted over or scraped off when one grows tired of it. It is easily damaged, stained, defaced, and replaced. Not many records of the wallpaper still remain, and if they do, they might be peeling off the walls of an abandoned summer resort in Union County, NJ, a historic house in Ohio, and even in my parent’s bathroom. In other cases, wallpaper preservation can be much more deadly. Some nineteenth century wallpapers were known to use pigments traced with arsenic, particularly the color green. One such book owned by Michigan State University has been practically shrink-wrapped by cautious librarians to prevent people from directly coming in contact with the arsenic-laden pages. Well-preserved wallpaper sample books are not only fantastically entertaining to flip through but they are brilliant artifacts of varying aesthetics, social changes, economic disparities, and personal preference across a period of time.

If you are interested in looking at the Janeway & Carpender wallpaper books at Rutgers Special Collections or learning more about the companies, you can search our holdings and Sinclair New Jersey Collection in the EAD finding aids, and contact the reference desk with any questions.

Resources:

Arcalus Period Design. http://arcalus.com

Bolling & Co. https://bollingco.com

Deserted Village, Union County, NJ. http://ucnj.org/parks-recreation/deserted-village/

Manufacturers’ Association of New Jersey. (1919). Manufacturers’ Association bulletin. Manufacturers’ Association of New Jersey. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112064282780

New Brunswick File Collection. NJ014. Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University. http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/ead/snjc/nbverticalfileb.html

New Jersey Trade and Manufacturers’ Catalog Collection. NJ009. Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

Scannell’s New Jersey’s first citizens and state guide. (n.d.). Paterson, N.J.: J.J. Scannell,.

Victoria and Albert Museum. A Short History of Wallpaper. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/short-introductory-history-of-wallpaper/

Zawacki, Alexander J. (2018). How a Library Handles a Rare and Deadly Book of Wallpaper Samples. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/shadows-from-the-walls-of-death-book