By Helene van Rossum

Helene van Rossum is a Dutch-born researcher and writer, who worked at SCUA as public services and outreach archivist in 2016-2018

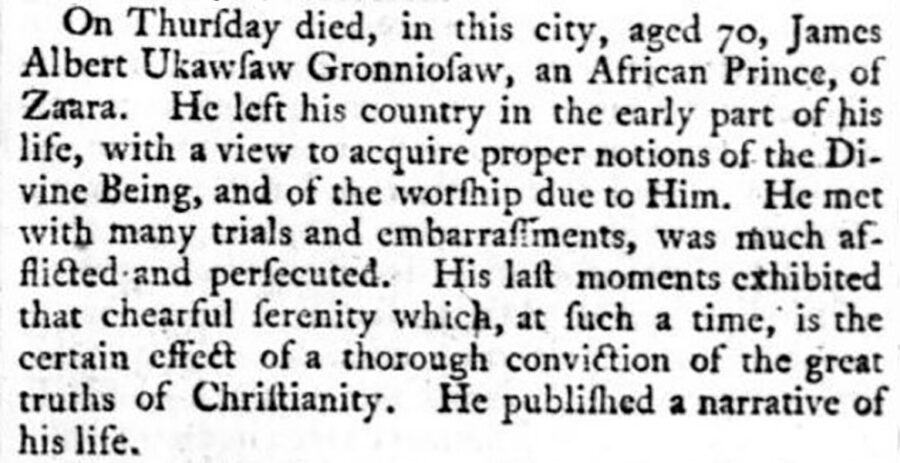

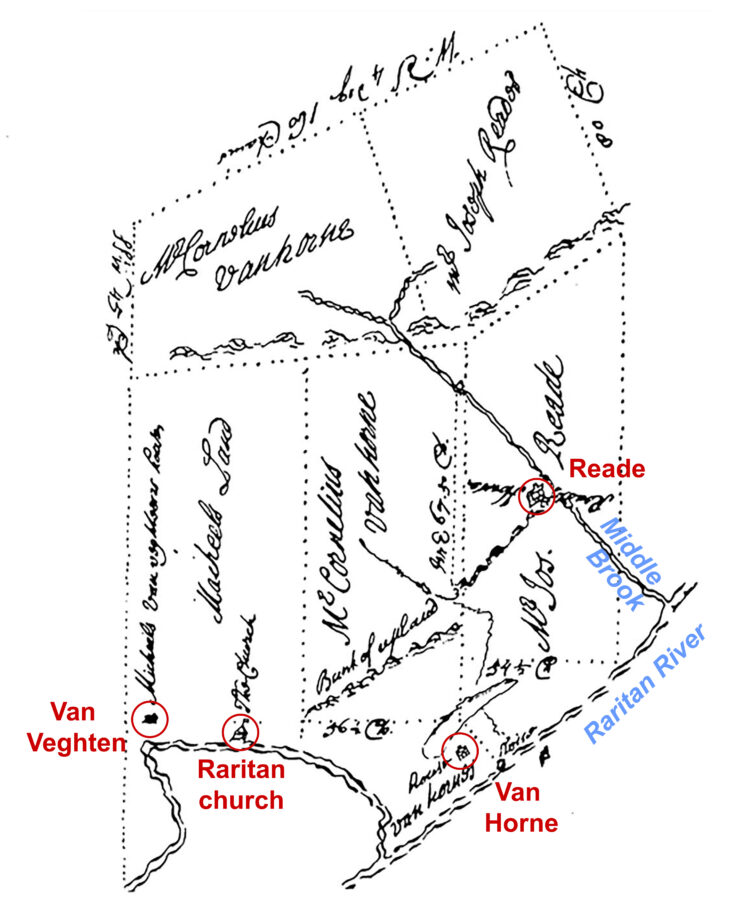

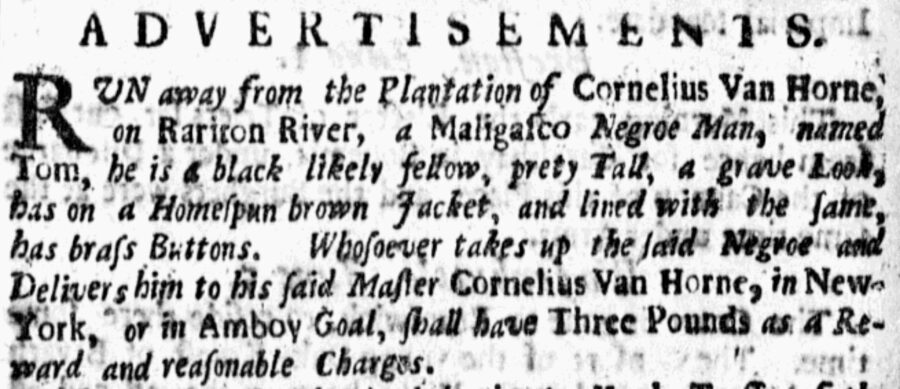

In our previous post we shared information about Cornelius Van Horne, the Dutch merchant in New York who enslaved Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (c. 1705-1775) on his plantation on the Raritan and sold him to his minister, Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. In this post we share insights about A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1772), the first book by a Black person to be published in Britain. According to historian Ryan Henley it should be seen in the context of the propaganda war between pro- and antislavery Calvinists in England, where Gronniosaw went to find George Whitefield, charismatic leader of the Great Awakening.

Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen (1691- c. 1747)

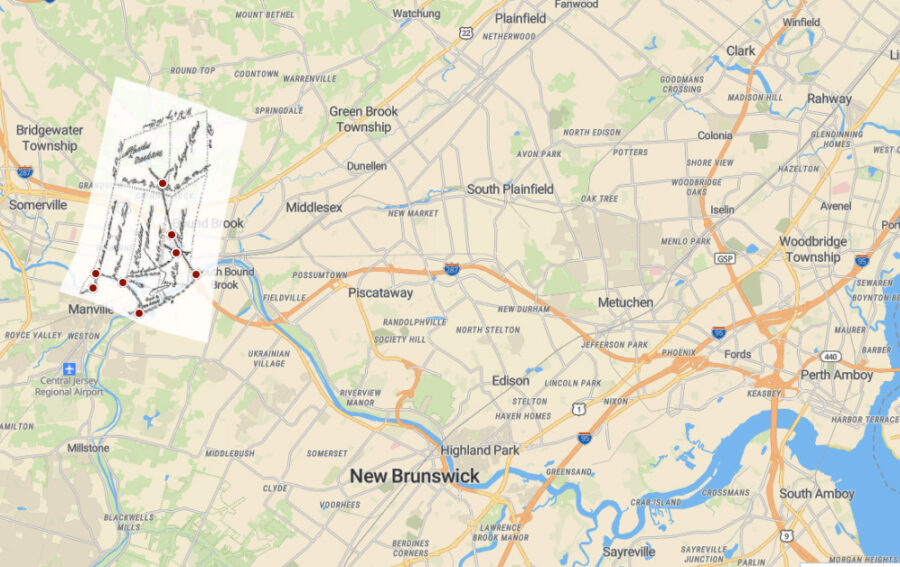

Dutch reformed minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen was 28 when he gave his first sermon to the Raritan congregation in January 1720, later the First Reformed Church of Somerville. The congregation had sent a call for a minister to Amsterdam together with the congregations of Three Mile Run, Six Mile Run, and North Branch (later the First Reformed Churches of New Brunswick, Franklin Park, and Readington, respectively). He resided in Three Mile Run, where he and his wife Eva Terhune–whom he met soon after his arrival–were given a farm.

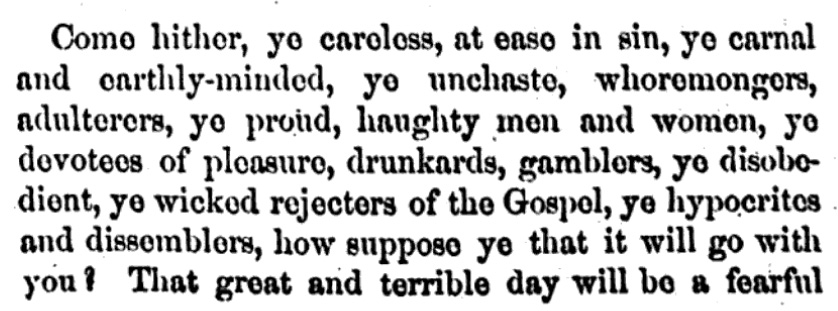

Frelinghuysen was not pleased with what he saw among his congregants. According to the translator of his first sermons he found that

great laxity of manners prevailed throughout his charge … that while horse-racing, gambling, dissipation, and rudeness of various kinds were common, the [church] was attended at convenience, and religion consisted of the mere formal pursuit of the routine of duty.

Passionate and blunt, Frelinghuysen caused a stir. Convinced that he could distinguish between the “generate” (the spiritually and morally reformed) and the “ungenerate,” he excommunicated three members of the community. This led a group of disgruntled families from all four congregations to appeal to the church authorities in the Netherlands (the Classis of Amsterdam), a conflict that lasted eighteen years.

“Focussed on the conversion of sinners rather than on the nurture of believers,” Frelinghuysen addressed his parishioners with fiery language.

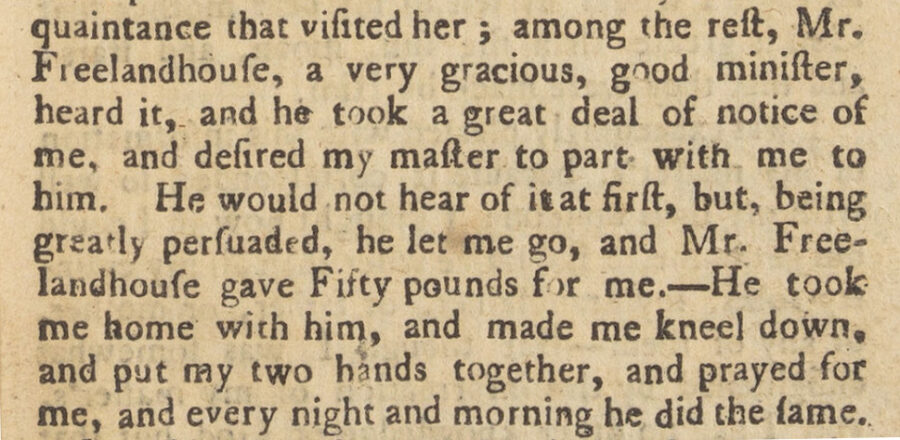

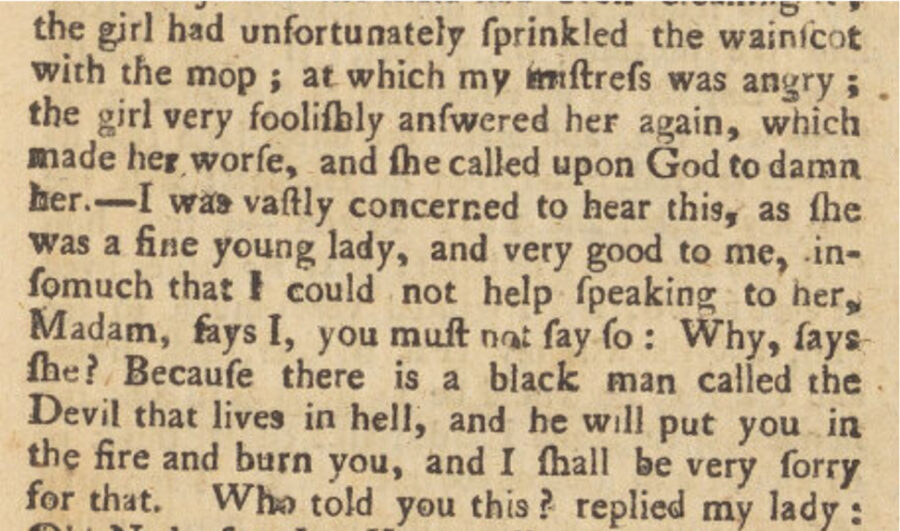

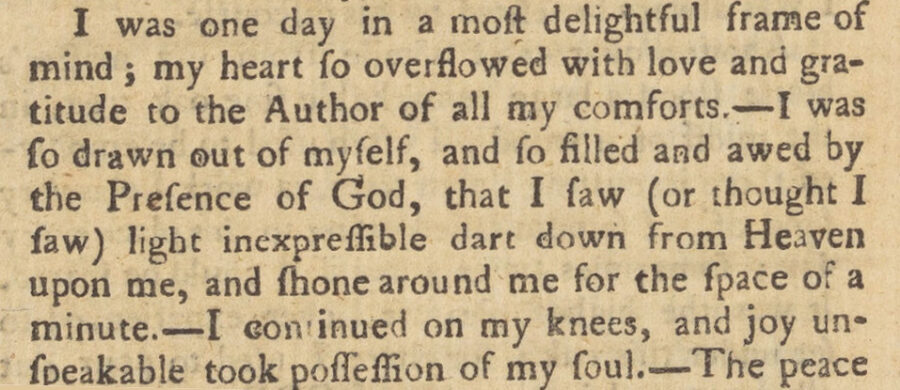

Among Frelinghuysen’s listeners was James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, whom the pastor had purchased after hearing how the young man had warned his mistress not to swear. He had asked a tutor, Peter Van Arsdalen (described as ‘Vanosdore’ in Gronniosaw’s Narrative) to teach him to read and write and school him in the Dutch Calvinist faith. It is no wonder that Gronniosaw underwent the experiential conversion that Frelinghuysen preached. According to theologian Joel Beeke “Frelinghuysen taught that only those are truly saved who have experienced conversion, which includes [ . . . ] not only the knowledge of sin and misery, but also the experience of deliverance in Christ, resulting in a lifestyle of gratitude to God.”

According to Ryan Hanley, “the final criterion of Frelinghuysen’s vision for salvation was fulfilled when Gronniosaw ‘blest God for my poverty, that I had no worldly riches or grandeur to draw my heart from him’.” But most important for pro-slavery Calvinists was what was written next. “Gronniosaw reconciled himself to his own enslavement, declaring that he ‘would not have changed situations [ . . . ] for the whole world.’”

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

Gronniosaw’s conversation was in line with what many Americans in the 18th century experienced in what became known as the “Great Awakening,” a time of spiritual renewal in the colonies among protestant congregations, with parallels in Europe. Presbyterian revivalist Gilbert Tennent (1703-1763), minister in New Brunswick since 1726, was one of the movement’s early leaders. He was great friends with Frelinghuysen and claimed to have learned a lot from his preaching.

The most important leader of the movement, however, was Anglican evangelist George Whitefield, founder of the Methodist movement in England together with the brothers John and Charles Wesley. Preaching mainly outdoors, he drew crowds in England as well as in the American colonies, which he toured seven times between 1739 and 1770. On November 20, 1739 he preached in New Brunswick three times at Gilbert Tennent’s church. In his journal he described Frelinghuysen as a “worthy old soldier of Jesus Christ,” who was the “beginner of the great work which I trust the Lord is carrying on in these parts.”

According to his autobiography, Gronniosaw was so impressed with Whitefield’s preaching that after the death of Frelinghuysen’s widow and sons he decided to go to England to search for him.

Gronniosaw was not the only Black person who was impressed by Whitefield. Among the thousands of people who came to hear Whitefield preach, a substantial number were enslaved. After traveling through the South in 1739 Whitefield wrote a passionate “letter to the inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, North, and South Carolina,” published in 1740 by Benjamin Franklin. He chastised Southern slave owners for mistreating their servants and not helping them convert to the Christian faith.

However, by the mid 1740s Whitefield owned a plantation and enslaved workers himself. Realizing he could not raise funds for an orphanage in Georgia without enslaved workers he became a leading proponent of legalization of slavery in Georgia, where slavery had been banned. According to church historian and biographer Thomas Kidd, Whitefield’s relationship to slavery represents the “greatest ethical problem in his career.”

Selina Hastings (1707-1791)

Whitefield died in 1770 during his seventh tour in the American colonies. In his will he had left his plantation and slaves, as well as the orphanage that he founded, to his patroness Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, who played an important role in the religious revival and Methodist movement in England and Wales. Though she and Whitefield were originally close to John Wesley, they grew apart over the Calvinist concept of predestination.

They disagreed about slave ownership too. In 1774, Wesley published his anti-slavery views in Thoughts on Slavery, while Selina Hastings had financed the publication of Gronniosaw’s Narrative two years earlier. Written with the help of a woman in Hasting’s circles, in the Narrative Gronniosaw seemed to embrace his enslavement as a means to get to know God.

In a preface of the 1790 edition minister Walter Shirley – a cousin of Selina Hastings – stated that the book provided the answer to the question how God will deal with “those benighted parts of the word where the Gospel of Jesus Christ hath never reached.”

For Walter Shirley the answer was clear. “Whatever infidels and deists may think; I trust the Christian reader will easily discern an all-wise and omnipotent appointment and direction in these movements.”

The financiers, producers, and readers of Gronniosaw’s text were “Calvinists seeking to prove that freedom was not necessary to achieve salvation,” Hanley concludes. “Many of them derived the bulk of their wealth from the institution. It can hardly be surprising, then, that the Narrative does not call for the abolition of the slave trade as some of its more famous successors would.”

The Frelinghuysen sons

When Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen was dying he told Gronniosaw that he had freed him in his will. Gronniosaw, who had already served the Frelinghuysen family for over twenty years, decided to continue to serve the widow and her children. All five sons became ministers, and the two daughters married ones.

The tragic story of the five Frelinghuysen brothers will be told in another post.

Contents of this blog post were shared in a presentation “‘That class of people called Low Dutch’: African Enslavement Among the Dutch Reformed Churches of Ulster County and New Jersey’s Raritan Valley,” by Helene van Rossum and Wendy Harris at Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY (April 7, 2018)

Further Reading

Balmer, Randall H. 2002. A Perfect Babel of Confusion: Dutch Religion and English Culture in the Middle Colonies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hanley, Ryan. “Calvinism, Proslavery and James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw.” Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 1 (2015): 360-381.

Matthews, Christopher, The Black Freedom Struggle in Northern New Jersey, 1613-1860, an illustrated essay in six parts

Tanis, James. 1967. Dutch Calvinistic Pietism in the Middle Colonies: A Study in the Life and Theology of Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff