Please join us in congratulating our colleague Dr. Fernanda Perrone on being named a Society of American Archivists Fellow. This award recognizes outstanding contributions to the organization and to the archives profession. It is the highest honor SAA bestows on an individual.

In the course of her over thirty year career, spent primarily here at Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives, Fernanda has made her mark on the profession through documenting underrepresented groups, mentoring emerging archivists, and fostering international collaborations. Her research focuses on women’s history, gender studies, the history of Rutgers, and the history of westerners in Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Read more about Fernanda and her many accomplishments on the Rutgers Libraries website.

New and Notable Fall 2024

As we wrap up the fall semester, we present some highlights of our recent acquisitions. From Special Collections and University Archives, we wish you a wonderful holiday season and happy reading and researching in 2025!

~~~~~~~~~

Household and property accounts for Eastridge, January 1848-July 1857. The ledger documents the complex and meticulous operations of Eastridge, sisters Mary and Louisa Rutherfurd’s home on the Passaic River in New Jersey.

Klüva, Billy. Billy’s Good Advice. (Bantam Press), 2002. Billy Klüva was a Swedish engineer at Bell Telephone Laboratories who collaborated with numerous artists. He co-founded, with Robert Rauschenburg and others, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Klüva performed in several Happenings by Claes Oldenburg, and this copy is inscribed to Oldenburg’s first wife, Patty Mucha.

Kompletna Lista Nowych Polskich Rekordow Victora (Ortofoniczne Rekordy). (Camden, New Jersey: Victor Talking Machine Company), 1929. Illustrated catalog of Polish records.

Lewis, Joel S., ed. Ahnoi. (Bergen, NJ), Spring 1980. Issue number 3. The many contributors include Allen Ginsberg, Ron Padgett, Alice Notley, and Amiri Baraka. Cover by Rochelle Kraut.

Map of the Country Thirty Three Miles around the City of New York. (New York: J.H. Colton), 1846. First edition pocket map.

New Testament. (New-York; John S. Taylor. Trenton, NJ: Bishop Davenport), 1835.

Ocean City, NJ’s Annual Hospital Fund Week, August 18-31, 1935. (Ocean City, NJ/Philadelphia, PA: Century Service Exchange), 1935. Program for a fundraising event that featured a host of notable African American guests, with advertisements from Black-owned businesses in the area. The printer, Frederic H. Hammurabi Robb (“Director, Travelor [sic], Author & African Interpreter”) was an African American attorney who toured the world speaking on Black history.

Silver, J.M.W. Sketches of Japanese Manners and Customs. (London: Day and Son), 1867. Jacob Mortimer Wier Silver was a British marine who was stationed in Japan from 1864 to 1865. Features 28 chromolithographs copied from illustrations by Japanese artists.

Victor Katalog Polskych Rekordow. Victor Polish Records (Orthophonic Recording). (Camden, New Jersey: Victor Division R.C.A. Victor Company), 1931. Illustrated general catalog featuring musicians, bands, and conductors.

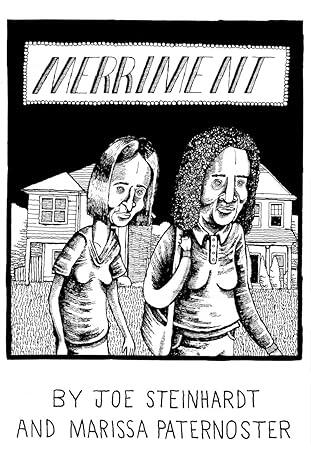

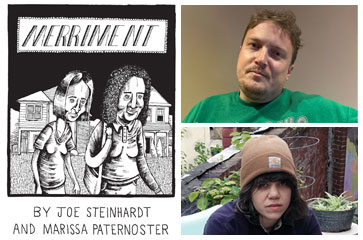

“Merriment” Book Reading and Q&A with Marissa Paternoster and Joe Steinhardt (Rescheduled)

Join the New Brunswick Music Scene Archive, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, as we welcome Marissa Paternoster (Screaming Females, Noun) and Joe Steinhardt (Don Giovanni Records) to read from and discuss their new graphic novel, Merriment, at Alexander Library in New Brunswick on Tuesday, October 1st at 4 p.m. This will also be an online event, link available upon registration. An exhibit of original artwork will also be on display, and copies of the book will be available for purchase and signing.

About Merriment: As many of us do, Mack is having a hard time coping with life in New Jersey. Watching her friends figure their lives out while she is stuck living at home, Mack is looking for any kind of lifeline out of her Mom’s house and into the City where she is convinced she will be happy. Then again, it’s hard for anyone to be happy these days, a fact her mother will not let her forget. And what’s worse: she thinks she might have committed a murder. And that maybe, just maybe, the FBI is spying on her? Merriment follows Mack on her quest for happiness and/or sanity through the horrors of life as she navigates existential dread, real-life dread, and all the dread in between.

Joe Steinhardt owns and operates Don Giovanni Records, a label that remains committed to furthering alternative culture and independent values, and providing resources for artists who prefer to work outside the mainstream music industry. He is a published author and an Assistant Professor at Drexel University in their Music Industry Program.

Marissa Paternoster is a visual artist, the lead singer and guitarist for Screaming Females, and was named the 77th best guitar player of all time by SPIN magazine and the 150th best of all time by Rolling Stone. Through her work with Screaming Females and her solo career, Marissa has released 11 studio albums and has been featured on MTV, Late Night TV, and NPR. She has toured extensively, supporting bands like Garbage, Dinosaur Jr., The Dead Weather, Arctic Monkeys, and The Breeders.

Date: Tuesday, October 1, 2024

Time: 4:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m.

Location: Alexander Library Teleconference/Lecture Hall – TLH (4th floor)

Summer Reading: New Local History Acquisitions

If you’ve already read plenty of fiction this summer, how about some local New Jersey history? Here is a selection of books newly cataloged to the Sinclair New Jersey Collection in Special Collections and University Archives. All can be read by appointment in our lovely air conditioned reading room with views of the College Avenue Campus. Contact us at scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu if you need a break from the beach (or just want to read about it)!

Douglas G. Abbott. Just a Kid from Paterson

Yael Aravah. Pineys: The People of the New Jersey Pine Barrens

Peter Astras. Lake Hopatcong: A History of New Jersey’s Largest Lake

James M. Carter: Rockin’ in the Ivory Tower: Rock Music on Campus in the Sixties

Patricia Chappine. New Jersey Women During World War II

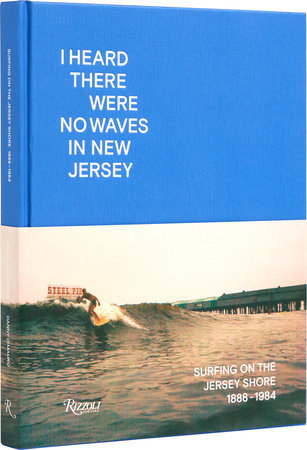

Danny DiMauro and Johan Kugelberg. I Heard There Were No Waves in New Jersey: Surfing on the Jersey Shore 1888-1984

Elizabeth Colmant Estes: Global Grace Cafe: A Love Story About Battles Lost and Won to Keep Families Together in America’s War on Immigrants

Peter Genovese. The Ultimate Guide to the Jersey Shore: Where to Eat, What to Do, and So Much More

Erik Kiviat and Kristi MacDonald. Urban Biodiversity: The Natural History of the New Jersey Meadowlands

Helen Lippman. Hidden History of Newark, New Jersey

Mafia Library. The Decavalcante Mafia Crime Family: The Complete History of a New Jersey Crime Organization

K.A. Nelson. Killing Shore: The True Story of Hitler’s U-Boats Off the New Jersey Coast

Michael Aaron Rockland. The George Washington Bridge: Poetry in Steel (Revised and Expanded)

New and Notable: Recent New Jersey Acquisitions

These items have been or will soon be added to the Sinclair New Jersey Collection in Special Collections and University Archives.

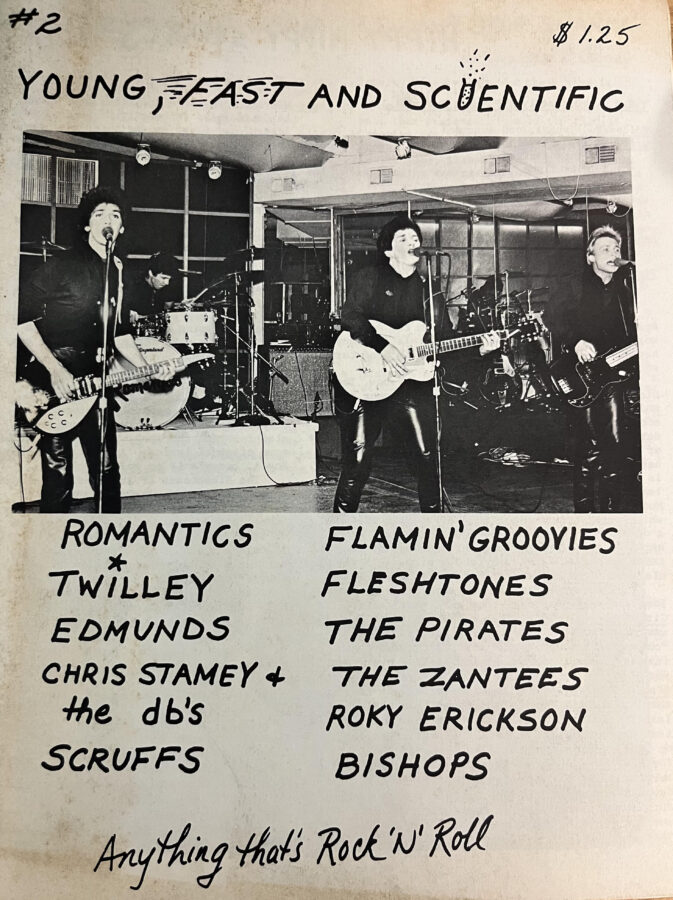

Abramson, Todd. Young, Fast, and Scientific zine, nos. 1 and 2 (Gillette, NJ: 1978 and 1979)

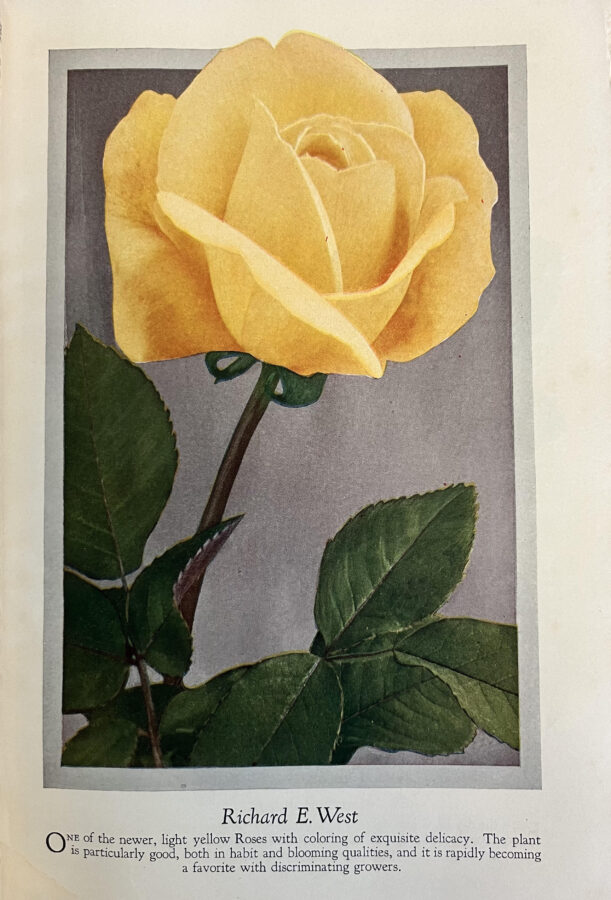

Bobbink and Atkins. Roses. (Rutherford, NJ: Bobbink and Atkins, 1929)

Congoleum-Nairn. Congoleum-Nairn 1941 trade catalog. (Kearny, NJ: Congoleum-Nairn, Inc., 1941)

Englewood Institute for Young Ladies, Englewood, Bergen County, New Jersey catalog (Englewood, NJ: 1864)

Paterson Rambling Club. Songs. (Paterson, NJ: Paterson Rambling Club, 1913)

Pickaninny Club Minstrel Show, at the Berkeley Lyceum, in Aid of the Daisy Fields Hospital for Crippled Children (1896)

Schrabisch, Max. Indian Vestiges in Garrett Mountain Reservation: A Series of Three Articles (Paterson, NJ: The Passaic County Park System, Lambert Castle, Garrett Mountain Reservation, 1939)

POSTPONED! “Merriment” Book Reading and Q&A with Marissa Paternoster and Joe Steinhardt

Event originally scheduled for this Thursday has been postponed. A new date will be announced soon.

“Merriment” Book Reading and Q&A with Marissa Paternoster and Joe Steinhardt

POSTPONED! New date will be announced soon.

Join the New Brunswick Music Scene Archive, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, as we welcome Marissa Paternoster (Screaming Females, Noun) and Joe Steinhardt (Don Giovanni Records) to read from and discuss their new graphic novel, Merriment, at Alexander Library in New Brunswick on Thursday, May 23rd at 4pm. An exhibit of original artwork will also be on display, and copies of the book will be available for purchase and signing.

About Merriment: As many of us do, Mack is having a hard time coping with life in New Jersey. Watching her friends figure their lives out while she is stuck living at home, Mack is looking for any kind of lifeline out of her Mom’s house and into the City where she is convinced she will be happy. Then again, it’s hard for anyone to be happy these days, a fact her mother will not let her forget. And what’s worse: she thinks she might have committed a murder. And that maybe, just maybe, the FBI is spying on her? Merriment follows Mack on her quest for happiness and/or sanity, through the horrors of life, as she navigates existential dread, real life dread, and all the dread in between.

Joe Steinhardt owns and operates Don Giovanni Records, a label which remains committed to furthering alternative culture, independent values, and providing resources for artists who prefer to work outside of the mainstream music industry. He is a published author and an Assistant Professor at Drexel University in their Music Industry Program.

Marissa Paternoster is a visual artist, the lead singer and guitarist for Screaming Females, and was named the 77th best guitar player of all time by SPIN magazine and the 150th best of all time by Rolling Stone. Through her work with Screaming Females and her solo career, Marissa has released 11 studio albums and has been featured on MTV, Late Night TV, and NPR. She has toured extensively, supporting bands like Garbage, Dinosaur Jr. The Dead Weather, Arctic Monkeys, and The Breeders.

Contact: Christie Lutz: christie.lutz@rutgers.edu

2024 Bishop Lecture: The Robison Hebrew Manuscript Collection: 50 Yemenite Treasures in Our Midst

Rutgers Distinguished Professor Gary A. Rendsburg will deliver the 35th annual Louis Faugères Bishop III Lecture, entitled “The Robison Hebrew Manuscript Collection: 50 Yemenite Treasures in Our Midst,” on Tuesday, April 2, at 4:00 p.m., at Alexander Library and online.

Gary Rendsburg holds the Blanche and Irving Laurie Chair in Jewish History at Rutgers University, with appointments in both the Department of History and the Department of Jewish Studies. He is the author of seven books and over 200 articles; his most recent book is How the Bible Is Written (2019).

Rendsburg earned his B.A. in English at the University of North Carolina (1975) and his Ph.D. in Hebrew Studies at New York University (1980). Prior to coming to Rutgers in 2004, he taught for 18 years at Cornell University.

Rendsburg has conducted extensive research on medieval Hebrew manuscripts at leading libraries, including the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Cambridge University Library, the Vatican Library, and the Library of Congress.

During his career, Rendsburg has served as visiting professor or visiting research scholar at the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, the University of Sydney, the Hebrew University, Bar-Ilan University, the University of Pennsylvania, UCLA, the Getty Villa, and the Pontifical Biblical Institute (Rome).

The Bishop Lectures feature diverse topics on book and manuscript collecting, printing history, and the use of rare books and manuscripts. The series is named in memory of Louis Faugères Bishop Jr.’s son, a prominent cardiologist and book lover who helped build one of the excellent New York private libraries at the New York Racquet Club.

To register visit https://libcal.rutgers.edu/event/12100082