By Helene van Rossum

Helene van Rossum is a Dutch-born researcher and writer, who worked at SCUA as public services and outreach archivist in 2016-2018

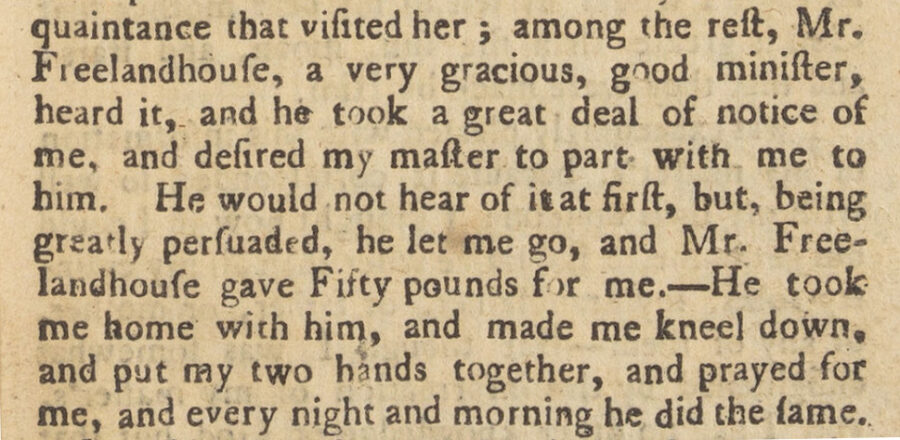

- Quote from A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1772) [source]

When Scarlet and Black’s first volume Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History came out in 2016, it was Rutgers’ connection to Sojourner Truth that made the headlines. The chapter about James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, enslaved servant of Dutch minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen–an early advocate of Queen’s College–did not get much attention. That is not difficult to understand, because Gronniosaw’s 1772 autobiography–the first book of a Black person to be printed in England–did not fit in the genre of abolitionist “slave narratives.” Just before the Scarlet and Black volume came out British historian Ryan Hanley published an article in which he not only identified the Dutch parishioner who sold Gronniosaw to his pastor, he also placed Gronniosaw’s book in the context of the propaganda war between pro- and antislavery Calvinists in England.

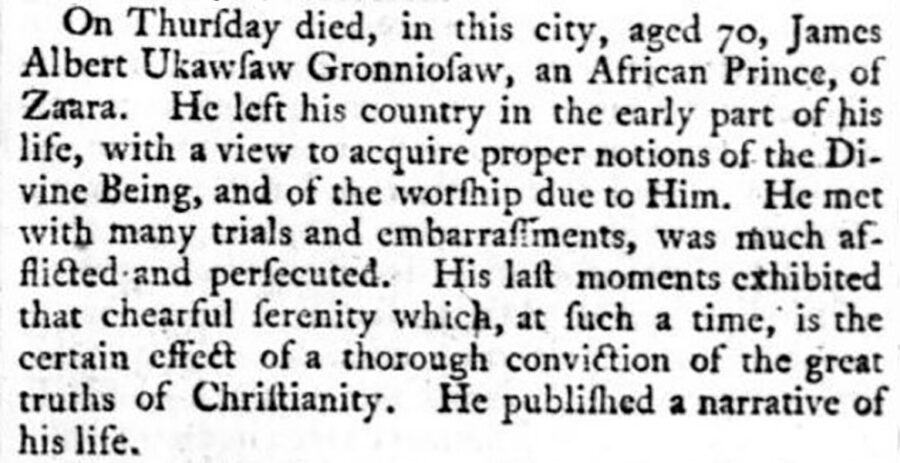

James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (c.1705-75)

- Obituary in the Chester Chronicle or Commercial Intelligencer, Chester, England, October 2, 1775 (Source)

Although he had spent most of his life in New Jersey, Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (who also used the name James Albert) died in England only three years after the publication of his book. According to his Narrative he was born an African prince, who willingly left his family and country as a young teen, because he was mocked for his belief in a power higher than the sun, moon, and stars that were worshiped at home. He ended up being sold to a Dutch captain who sailed to Barbados, where the boy was purchased by a young Dutch merchant with the name “Vanhorne,” who lived in New York.

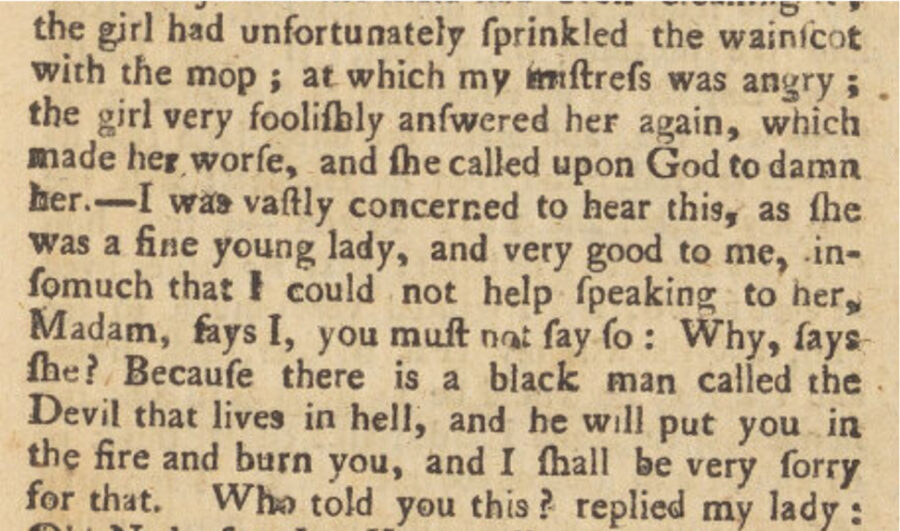

Put to work as a house servant, the teenager’s second language became Dutch, which apparently included a lot of swearing. Everybody swore, according to Gronniosaw, so he did so as well. An old enslaved servant named Ned overheard how he scolded a servant girl and “called upon God to damn her.” Ned warned him about a “wicked man called the Devil, that lived in hell” and would burn all people who used those words.

- Quote from A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1772) [source]

Terrified, Gronniosaw immediately stopped swearing. When he overheard his mistress swearing herself he felt obliged to warn her about the consequences. She shared the story with everybody in the neighborhood, which must have included Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. He had been minister of Raritan and three nearby Dutch churches in the Raritan Valley since 1720. But if she lived in New York, how would they have met?

Cornelius Van Horne (1693-1768)

The Van Horne family was a prosperous family of merchants in New York. According to Jan Cornelis Van Horne and his descendants the family’s founder and his young family emigrated from the Dutch city of Hoorn to New Amsterdam by 1645. His son Cornelius, a furrier and hat dealer, had three sons who all became wealthy merchants: Jan or John (1669-1735), Gerrit (1671-1737), and Abraham (1677-1741) van Horne. They traded, among others, from Barbados, owned land in New Jersey, and can be found among the sloop owners bringing captives into New York.

Looking for the “young, Dutch merchant” among the next generation Ryan Hanley identified Jan’s son Cornelius Van Horne (1693-1768) as the one who purchased Gronniosaw from a Dutch captain sailing from Barbados. That would have made Elizabeth French, who married Cornelius Van Horne in 1718, the young, swearing, mistress whom Gronniosaw wanted to save from hell. Her father, wealthy New York merchant Phillip French, had owned a property of 2754 acres on the Raritan River in Somerset County, which was split between his two surviving daughters in 1722, when Elizabeth’s sister Anna got married to Joseph Reade.

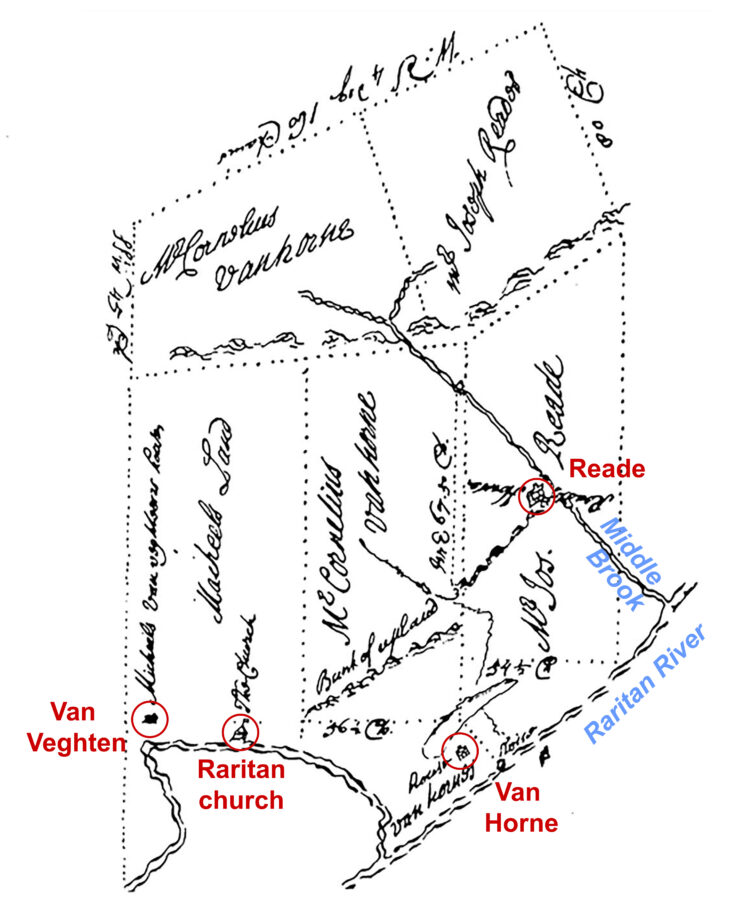

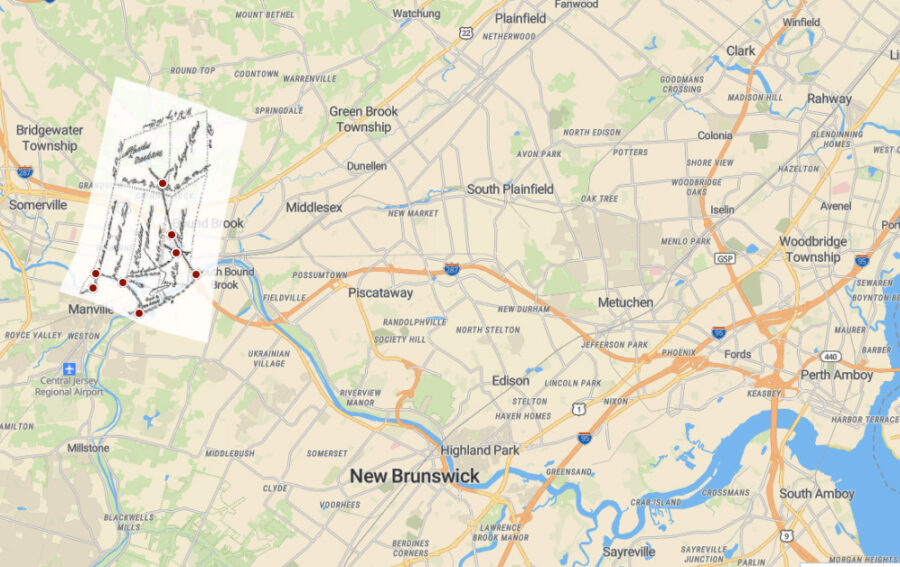

The above map that accompanied the deed shows how Philip French’s property, which bordered the estate of the prosperous Dutch farmer Michael van Veghten in the west, was divided between the two sisters and their husbands. All buildings are circled in red, including the homes of Van Veghten and of Cornelius Van Horn and Elisabeth French, known as “Kells Hall.” The home of Joseph Reade and Anna French on the eastern side was purchased by Cornelius Van Horne’s son Philip in 1750, known as “Phil’s Hill,” presently the Van Horne House. In addition, the map shows the Dutch church on Michael Van Veghten’s property, close to the bridge that he built at the location of the present-day Van Veghten bridge. Known as the Raritan church, it was one of the four Dutch churches where itinerant pastor Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen preached.

The Van Horne plantation

In a list of members of the Council of New Jersey, Van Horne, who served on the council from 1727 to 1740, is described as dwelling about 22 miles northwest from (Perth) Amboy. In 1774 the estate was described as containing about 1400 acres of land, with a large brick dwelling house (Kell’s Hall), orchards, a grist mill, a smelting house, barns, stables and various outhouses. How many enslaved laborers worked on the plantation we do not know, because Cornelius’s will is only known as an abstract.

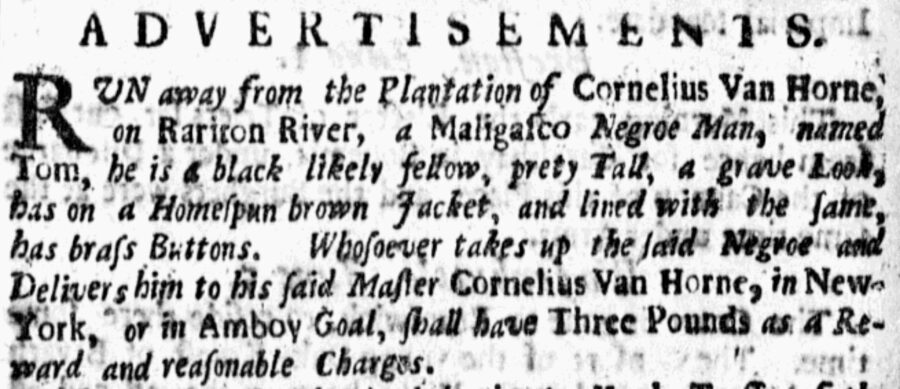

When Cornelius Van Horne and his wife Elisabeth were assigned their half of the estate in 1722–with the Raritan church at walking distance from their home–Gronniosaw was about seventeen years old. We do not know when he was purchased by Van Horne and how long he worked for the family before he was bought by Frelinghuysen, sometime in the 1720s. But Gronniosaw, who served in the house and not in the fields, may very well have known Tom, the tall Black man with the “grave look,” who according to the above ad that Cornelius van Horne placed in September 1724 ran away from the plantation that month.

Emotionally attached to the Frelinghuysen family, however, Gronniosaw would make very different choices, as will be seen in our following blog post “Updates about Ukawsaw Gronniosaw. Part 2: Frelinghuysen’s convert.”

With thanks to retired librarian, poet, and professional genealogist Sharon Olson, for verifying this Cornelius Van Horne is the young merchant who purchased Gronniosaw (possibly through his father Jan) and sold Gronniosaw to Frelinghuysen. Sharon is the author of ‘The Early Sandford Family in New Jersey Revisited,’ a series of nine articles in The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey. (2016-2019)

Further Reading

Cooper, Nathalie F. “New Insights Into Old Places, “Kells Hall,” “Phills Hall,” and the Janeway and Broughton Store.” Somerset County Historical Quarterly 1882-1982 commemorative issue, (1982): 3-12

Hanley, Ryan. “Calvinism, Proslavery and James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw.” Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 1 (2015): 360-381.

Matthews, Christopher, The Black Freedom Struggle in Northern New Jersey, 1613-1860, an illustrated essay in six parts