By Flora Boros and Helene van Rossum

Whether you’re a food scholar, cooking blogger, or an amateur chef looking to try your hand at a new recipe, Rutgers’ Special Collections and University Archives has something for everyone. You can study gastronomic fashions in rare books like John Evelyn’s Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets (ca. 1699) or Sarah B. Howell’s booklet, Nine Family Breakfasts and How to Prepare Them (ca. 1891). You can see how food and medicine mingled in herbal manuscripts like John Gerard’s The Herball, or a Generall Histoire of Plantes (ca. 1633) and admire Elizabeth Blackwell’s copper-plate engravings in A Curious Herbal (ca. 1739). Alternatively, you can learn about table settings and managing servants in The Lady’s Companion (ca. 1753), find out how to “preserve a husband” in Cook Book of the Stars (1959), or how to avoid alcohol in food in New Jersey’s earliest cookbook, Economical Cookery (ca. 1839), written at the time of the Temperance Movement. Or why not just try out one of the recipes in the Newbold family’s farming ledger (ca. 1800), or in the 4,000 local recipe books in our Sinclair New Jersey Cookbook Collection?

Earlier this month, we challenged the students in Dr. Lena Struwe’s Byrne Seminar on Food Evolution to dig into a fraction of our holdings concerning culinary history, recipes, cookbooks and global food exchange. Below are some highlights from materials we pulled for the class.

Herbals

An herbal is a compilation of information about medicinal plants including their botanical identifiers, habitats, therapeutic effects on the body, and medicinal preparation. All herbals follow the same pattern: for this condition, take this plant, prepare it in a certain manner, administer it, and expect this result. Throughout Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, herbs might not have been ranked high on the European gastronomic table, but they were well-established remedies, and with the help of herbal recipes the cook was expected to keep a household healthy.

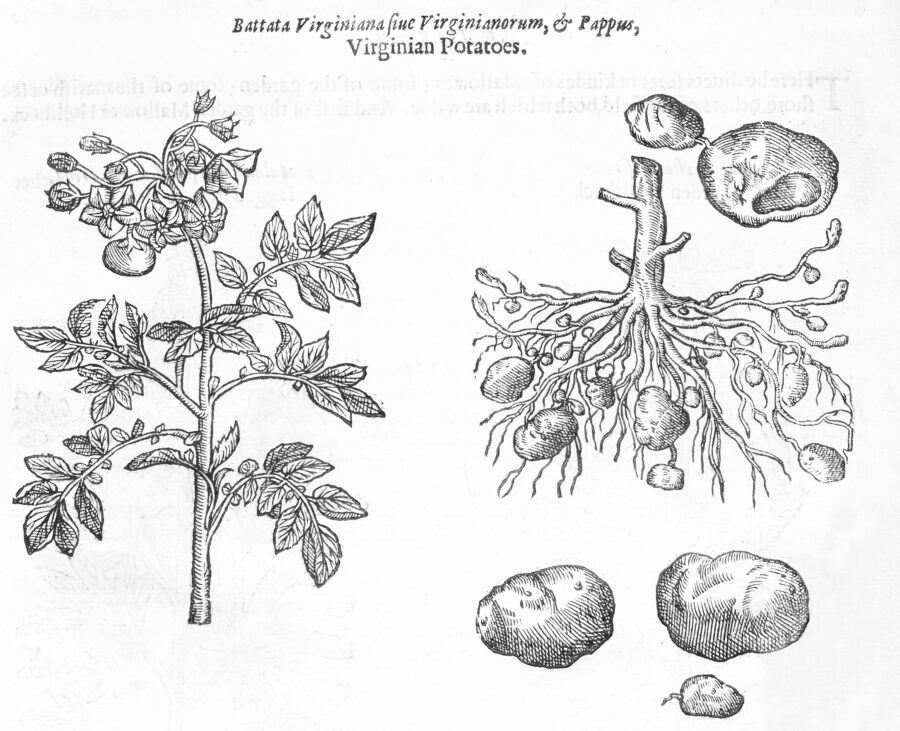

Written by one of the most respected plant experts of his time, John Gerard’s thick tome, The Herball Or, Generall Historie of Plantes (ca. 1633) included the first descriptions printed in English of New World imports like potatoes, corn, yucca, and squash.

Notably, The Herball contains images that would have been the first that most English speakers would have seen of the potato. Although the plant was brought to England in 1586, it was not until the early eighteenth century when the potato finally became a staple in the European diet. Ahead of his time, Gerard commended potatoes as a “wholesome” food, best prepared “either rosted in the embers, or boyled and eaten with oyle, vinegar and pepper.”

To illustrate The Herball, publisher John Norton rented nearly 1,800 of the most accurate illustrations of the time, woodblocks from the Frankfurt publisher of the “father of German botany,” Jacobus Theodorus’ Eicones Plantarum (ca. 1590). Norton commissioned sixteen additional woodcuts of plants. Among the edible imports was an illustration of the potato, supposedly illustrated from a specimen grown in Gerard’s garden that was given to him by Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake.

Rare cookbooks

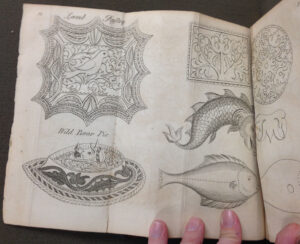

The French Cook: A System of Fashionable and Economical Cookery (ca. 1822) was perhaps the most extravagant work on French cookery published in England up to that time. By the eighteenth century, French food had been clearly established as the most popular type of cuisine in Great Britain. As was typical for the time, the author modified French techniques, Anglicized recipes while keeping French terminology, and equated French food with expense and extravagance throughout the introductions and commentary framing the recipes.

Such cookbooks targeted Britain’s middle classes, who desired fashionable displays of wealth and sophistication, straight from the mouth of the former cook to Louis XVI and the Earl of Sefton, and steward to the Duke of York. In a world that was becoming increasingly globalized, cookbooks meant that it was easier than ever to create an enviable lifestyle. Industrious Brits could serve an elaborate wild boar pie based on Ude’s pastry patterns, creations that epitomized Britain’s nobility—the ultimate expression of a life of wealth and ease. If you flip through its pages, you will surely notice how this book was written for English “gentlemen” and “ladies,” terms which became associated with a specific type of attitude, wealth and sophistication rather than family history.

In contrast to the male “food artists” coming out of France, women who wanted to establish a professional presence as a cookbook author framed their books by drawing on experience as wives, mothers, and housekeepers. Relegated by feminine stereotypes, female cookbook authors sold themselves as experts in all matters of the household, not just as cooks. As women ventured into this male-dominated realm, cookbooks slowly evolved into manuals of instruction for amateur cooks and housekeepers to maintain hearth, home, and familial values.

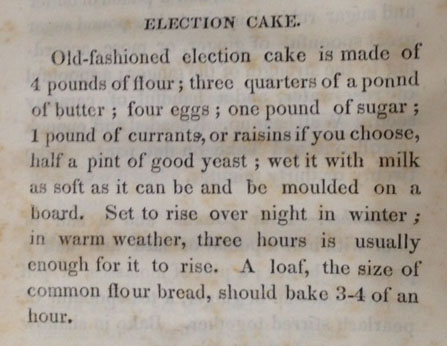

Late to the gastronomic game, Americans only began publishing cookbooks in 1742. Nearby New York and Philadelphian publishers cornered the market until New Jersey’s first cookbook, Economical Cookery: Designed to Assist the Housekeeper in Retrenching Her Expenses, by the Exclusion of Spiritous Liquors from Her Cookery (ca. 1839). It was written by an anonymous female author who urged women to take an active part in the Temperance Movement by eliminating liquors from their cooking and thereby safeguard their families from “the debasing slavery” of alcoholism.

Among her booze-free recipes is election cake, a culinary creation dating back to 1660 that makes the rounds every election. Originating from when food and “ardent spirits” were persuasive agents for controlling local votes, both were dispensed lavishly as bribes and rewards. Be sure to check out NPR’s coverage, “A History of Election Cake and Why Bakers Want to #MakeAmericaCakeAgain,” complete with audio!

Sinclair New Jersey cookbook collection

In addition to cookbooks in our rare book collections, we hold a great number of recipe and cookbooks in the Sinclair New Jersey Cookbook Collection. The collection includes 4,000 recipe books from New Jersey towns, churches, schools, organizations, and companies that were primarily written by and for the middle class (View recipes sampled in previous blogs).

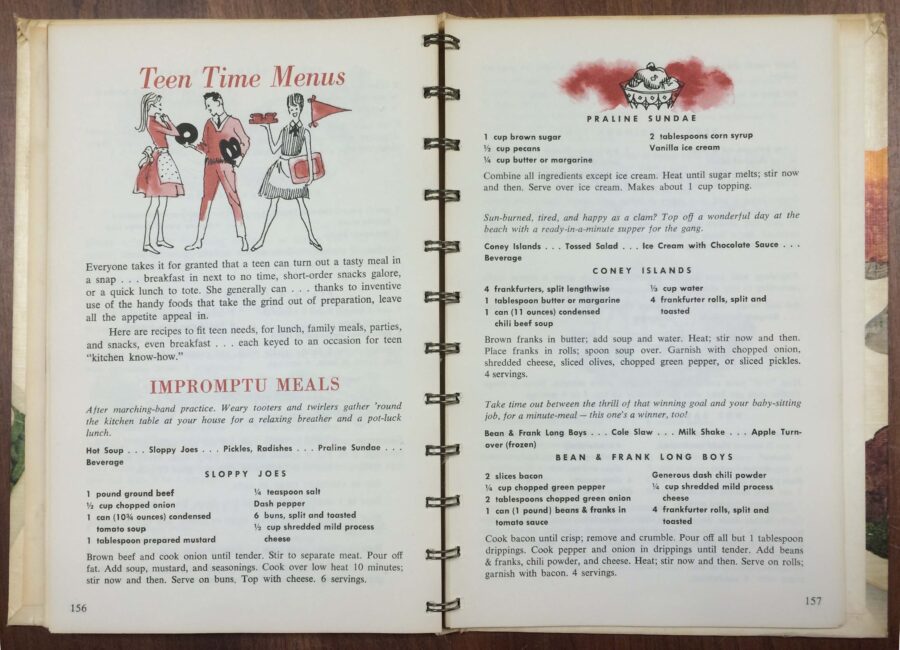

The collection includes privately and commercially produced recipe books, typically written for women. Among the commercial ones is a recipe book from the New Jersey based Campbell Soup Company, published in 1910 for “the ambitious housewife, confronted daily with the necessity of catering to the capricious appetites of her household.” The booklet has menu suggestions for every day of the month, with a Campbell soup as one of the courses for lunch or dinner or both. Another Campbell recipe book, shown above, addresses not only the women of the 1950s, but also future consumers: teenage girls. The section “Teen time menus” includes cheerful references to marching band practice, babysitting jobs, and being “happy as a clam.”

A great number of the non-commercial recipe books are produced by women communities of various denominations, often for fundraising purposes. One of the more unusual ones is the Cook Book of the Stars, printed in 1959 by a Flemington chapter of the Freemason society “Order of the Eastern Star,” which ended its list of recipes–tongue-in-cheek–with a recipe “how to preserve a husband” (displayed on top).

Newbold family account books

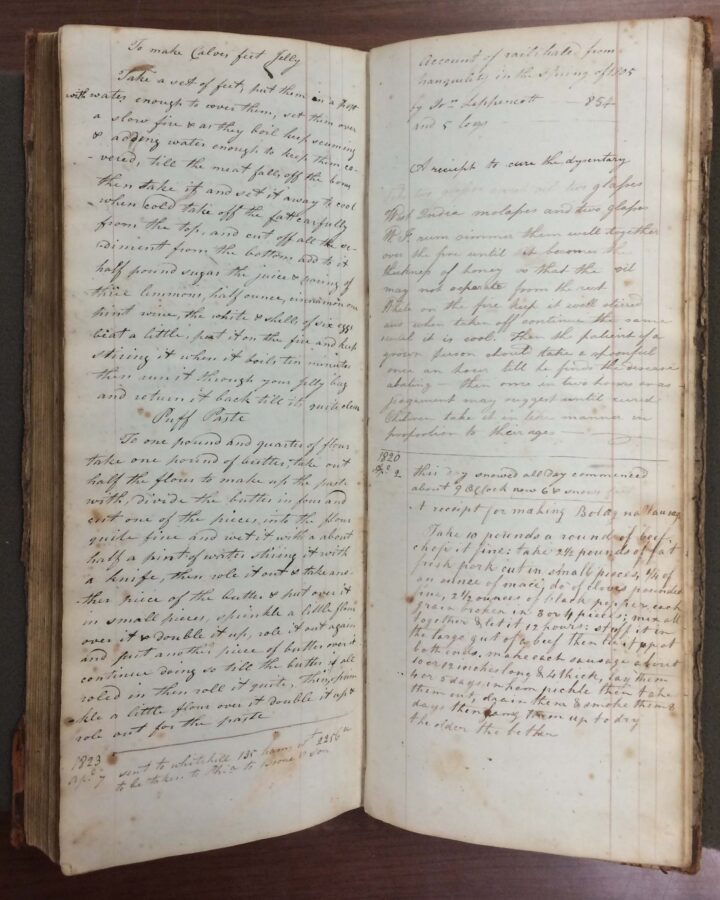

A more unusual place for New Jersey recipes is one of the five farm account books, kept by Thomas Newbold (1760-1823) at Springfield township, Burlington County, and his son Thomas Jr. The first three of the volumes, which altogether span almost eighty years (1790-1877) are “day books:” daily accounts and memoranda of transactions and agreements that were later transferred to ledgers. Among the regular entries on the last few pages of the first day book are a few recipes for dishes and remedies for cures, jotted down in different hands, either from Newbold family members or customers visiting the farm. The food recipes include calves feet jelly, puff paste, bologna sausage, and cured ham, while the remaining recipes are remedies for dysentery, cancer sores, felons (finger infections) and botts in horses (a disease caused by botfly maggots in a a horse’s intestines or stomach).

Whether looking for recipes or remedies, visitors are always welcome to browse the collections at Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives. Bon appetit!

beautifull blog,thanks.