November 11, 2018 is Veterans Day and marks the 100th anniversary of the Armistice that ended World War I. To commemorate this centennial, What Exit? will be featuring letters from Special Collections and University Archives’ Records of the Rutgers College War Service Bureau. This collection features letters from Rutgers students and alumni who served in the First World War, describing their experiences serving in the United States and overseas. Each day between November 1 and 11, Voices of the Armistice posts will share what these Rutgers students from 100 years ago had to say about the moment when peace was declared.

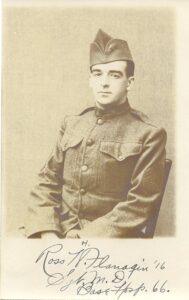

Ross H. Flanagin (later Flanagan) (class of 1916) was serving with Medical Services in the American Expeditionary Forces in France when the Armistice was declared.

“Well after a while, Fritz thought he had enough of it. He was tired of the rough handling of the Doughboy and decide to ask for an armistice. You remember the day—the 11th of November. It was some day at quiet old Neufchateau. Up until that day the town had been dark at nights. There were no lights in the streets. No lights in the windows of the houses. No lighted store windows to entice within the unwary rank in order to releive [sic] him of his superfluous francs. But on the night of the 11th—Oh Boy!

Four of us walked down to the town that night to help celebrate. We did not know what would happen but were going to be there anyway. As we approached the town we saw for the first time lights in the streets. From some point in the town rockets were shooting up into the sky and bursting with brilliant light. Shop windows were lighted and strange looking sights they were. As we got further into town the crowd became denser. The streets were full of soldiers—French American, Italian, a few Russians and two German prisoners who were cleaning up the last corner to make possible clean streets for the celebrants. At the crossing of the main streets the crowd was so dense that it was necessary to use some of Sanford’s famous tactics to get through. We did after a while and went on our way—at a pace slower than that of the proverbial snail. Rue St. Jean was certainly a pleasant sight. Every house was lighted. Many had lights in the windows. One house in particular attracted our attention. The second story windows of this house were lined with candles—the window sills, y’know. I have never seen anything like that before. It surely made a pretty picture.

About half way up the Rue St. Jean the Italian band was gathered. Before them were stationed poilus as lantern bearers. Soon the signal was given to start. The band struck up some joyful air and off they moved. All the people in the street followed them. It was not long before nearly all the people in town were marching in the procession. Up and down the streets of the town we marched. After much marching and counter-marching we brought up in front of one of the chateaux in town. Here some French officials had there [sic] quarters. An American officer—it was said that he was some General—made a short speech in English. He said that it was the first time in four years that lights had been permitted in the town at night, that the armistice had been signed, that we would soon be on our way back to America and that he expressed the hope of the French people of the town that we would always remember kindly the people we had come over to help. Then a French official made a short speech in his own tongue. At the end the band played The Star Spangled Banner—and, Silvers you do not know how it made our hearts swell to hear our National Anthem! This was followed by the Marsellaise, and much cheering for both nations.

The band then led the way for another promenade about town playing that most catching air of the French “Madalon”. We marched and counter marched some more and arrived at Jeanne d’Arc Square. Here a French girl sang the Marsellaise and the Star Spangled Banner. She followed this by singing “God Save the King”—but we poor simple Americans who appropriate everything all joined in the singing by lustily proclaiming “My Country T’is of thee.” The we marched some more, singing and shouting, pushing and shoving everyone else around and having a general good rough time.

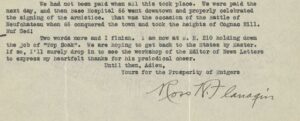

We had not been paid when all this took place. We were paid the next day and then Base Hospital 66 went downtown and properly celebrated the signing of the armistice. That was the occasion of the battle of Neufchateau when 66 conquered the town and took the heights of Cognac Hill. Nuf Sed!

After the war, Flanagin became a clergyman with the Episcopal Church and changed the spelling of his last name to Flanagan. He died in 1982

The Rutgers War Service Bureau was formed in 1917 as a way to keep Rutgers men serving in the war in touch with Rutgers and each other. It was headed by Earl Reed Silvers (class of 1913), who was assistant to Rutgers president William Henry Steele Demarest. Thanks to a grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, the letters are now available online.

Be sure to visit What Exit? between November 1 and 11 for new stories and follow highlights on Special Collections and University Archives’ Facebook and Twitter.

(With assistance from Tara Maharjan. Flanagin photo from the Rutgers University Biographical Files: Alumni Collection.)