By Rachel Ferrante

In these uncertain times, can I offer you Douglass College Arts History from 1945-1975?

I want to start with a story called “Cumberland Street,” which was published in the Anthologist literary magazine in 1950. I believe that the controversy surrounding this short fiction underscores how different Rutgers culture was at the beginning of this period. Reflective of American culture of the time, Rutgers in 1950 had strict standards for the behavior of its students. For many years, the Douglass College student handbook (the Red Book), listed “willfully breaking social code” as grounds for suspension or expulsion. “Cumberland Street” follows three students who are not just breaking rules but laws, and doing so to commit what some New Jerseyans felt was an obscene attack on morality: abortion. The correspondence between angry New Jerseyans, religious leaders, and reporters spanned three university presidencies, and resulted in a few pauses in publication. Rutgers President Mason Gross was the one to put a stop to it by issuing an official endorsement of the magazine on September 11, 1960. In his letters to business leaders and reporters, Gross was respectful but emphasized his duty to defend students’ freedom of expression. Although the focus of my research has been to illustrate the impact of women artists on the university’s arts programming, I felt like this story was worth retelling because it portrays Mason Gross as a supporter of the arts and free speech. Supporting one without the other, I think he would agree, is insufficient.

Therefore, his name is rightfully attached to Rutgers’ school of the arts. However, the foundation that Mason Gross School of the Arts (MGSA) was built upon is quite literally dependent on female artists, and one microbiologist, Mary Ingraham Bunting. During Bunting’s tenure as dean of Douglass College from 1955 to1960, she made several important changes to the curriculum. Prior to Bunting, Margaret Trumbull Corwin had been the dean of what was then known as New Jersey College for Women (NJC) for 21 years, from 1934 to 1955. Some accounts of her tenure portray her negatively; however, her focus on internal improvements to the college through the World War II era laid the foundation for the vibrant Bunting years. Here are some of Corwin’s contributions:

- Developing an annual lecture series that would lead to renowned figures in all fields visiting Douglass, including artists.

- Expanding experiential learning so that by 1937 one third of all courses had field trips.

- Dissolving the clothing major and replacing it with Costume Design housed in the Fine Arts Department.

- Expanding interdisciplinary study opportunities by allowing students to create their own majors.

- Developing a recruitment program to draw students during and after the war.

- Using connections between NJC and Rutgers to have a university-funded student center built.

- Holding showcases of faculty work, specifically within the Fine Arts Department.

These showcases continued after her tenure. In 1956, Douglass art professor Robert Watts, then in his third year at the college, displayed his work to a crowd that included a chemist from Johnson & Johnson named George Brecht. Brecht, who had been exploring “the art of chance,” approached Watts, and soon was introduced to Allan Kaprow, a Rutgers College art professor who also began teaching in 1953. A key influence on Brecht and Kaprow was John Dewey. Dewey’s theories of education were also part of the ideology of Black Mountain College (BMC), a short lived but progressive institution that emphasized the importance of art-making in a liberal arts education. Following the 1950s, Dewey’s ideas of a democratic, individually-driven education were growing in popularity as social codes were also changing. At Douglass, Kaprow, Watts, Brecht, and their cohorts continued the legacy of BMC by using the college’s space for inter-media art installations, one of the first of which took place taking place in College Hall, the administration building.

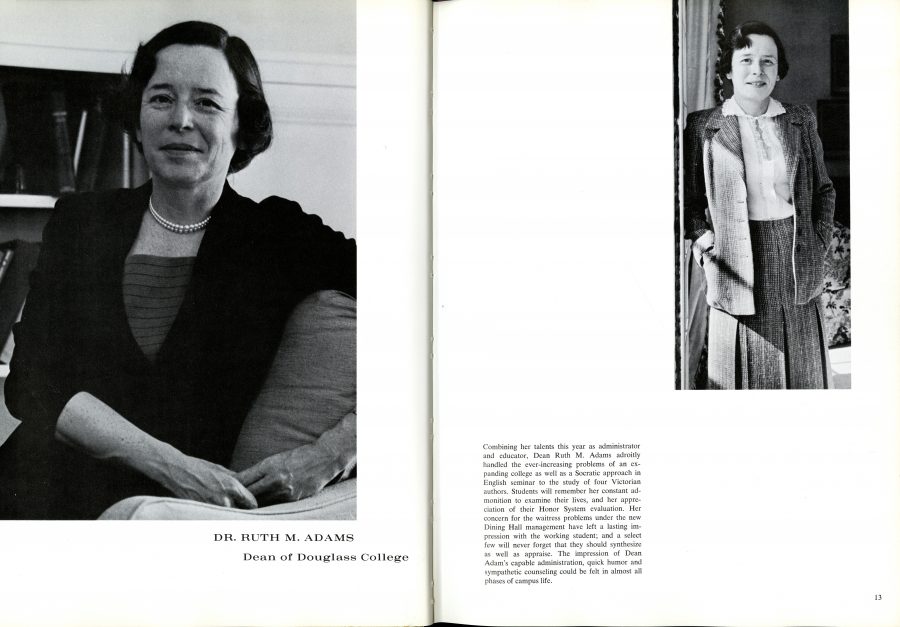

The genre largely associated with these artists is Fluxus, an interdisciplinary movement including composers and performers, which focused on the artistic process rather than the supposed quality of the final product. Fluxus played a large part in changing how art was being taught and practiced at Douglass. The events that resulted from this movement, Happenings, expanded the importance of art in campus culture, attracting students who were not just interested in art, but radical art. Taking over for Corwin in 1955, Mary Bunting’s time at Douglass, as one author put it “saw the glitter and flamboyance of the [Dean] Douglass years return.” In 1960, her successor Ruth Adams worked closely with President Gross to develop the precursor to the school of fine arts. With these women at the helm, Douglass was able to provide an equitable arts education to women who would go on to become innovative artists themselves.

Well into the sixties, art courses took place on the top floors of Recitation Hall, now the Ruth Adams Building. These courses became increasingly popular as the college grew. In 1961, the Mabel Smith Douglass Library was built, freeing up space in Recitation Hall for more courses. In 1964, liberal arts courses moved to the newly built Hickman Hall, and in 1965 Recitation Hall was renamed the Arts Building. Among the Douglass women studying there were Rutgers MFA students. This period was one of exciting growth at Douglass. One of Bunting’s early goals had been for the student body to reach 3,000 by 1968, which it did, expanding from only 600 students in 1942. With these new students came more diversity and therefore a need for more collaborative and progressive approaches.

These developments occurred both from the ground up and from the top down. While coeducation was never the priority of Douglass College, it started to become a university necessity to accommodate the growing student body. By the late sixties, although men’s degrees were from Rutgers and women’s degrees from Douglass, men and women could attend classes at either campus and in 1969, at the new “urban” Livingston College. One of the ways the University began to integrate was through the “Arts Section” created by Ruth Adams and Mason Gross in 1960. The section consisted of members of Douglass, Rutgers, and Newark visual arts programs and was the official precursor of the School of Fine Arts, as stated in Section II of the document. Section I outlines the primary intent: to paraphrase, the Arts Section was created to strengthen and unify the visual arts curriculum at the university and guide the development of arts programming at other Rutgers’ colleges, including Livingston and Camden. In a letter to the members of the Art Section dated March 10, 1960, Gross writes that “unnecessary duplication must be eliminated,” and that “Douglass and Rutgers can no longer operate separately.”

Touching on a common cultural connection, Gross acknowledged the proximity of New Brunswick to the art scene in New York and cited it as advantageous to Rutgers arts programming. He did make it clear, however, that he wanted Rutgers to have an arts program of its own significance. Gross also expressed a desire for the arts to be integrated into academics and the New Brunswick community at large, seeing the university as a cultural center, and Rutgers having an obligation to the state of New Jersey to develop its own cultural output. With growing interest in Fluxus/Happenings and the “New Jersey School” of art, Brecht and Kaprow began taking classes at the New School for Social Research in 1959. This marked a turning point for the artists. By the mid-sixties, they were well known outside of Rutgers for the movements they pioneered, and therefore became “New York Artists,” no longer associated with New Brunswick. As it turned out, New Jersey influenced New York arts rather than the other way around. In 1965 Brecht stopped working as a chemist, using his education at the New School to inform his art career. Kaprow worked at Rutgers until 1961. Watts would continue at Douglass until 1984, alongside artists Geoffrey Hendricks (1956-2003) and Roy Lichtenstein (1960-1964). The first female faculty member, artist Carolee Schneemann, wasn’t hired until 1976, as an adjunct.

The arts section had a number of policies. I will focus on two. The first is policy number four–that art museums, exhibition programs, and galleries will be integrated into buildings, no longer as separate spaces. The second, policy number seven, called for an expansion of facilities for the arts. These policies are still being enacted university–wide, especially on the Douglass Campus. An example of how these policies manifested on campus is the Mary H. Dana Women Artist Series housed in the Douglass library. The series, which is the oldest continuous exhibition series showcasing women artists in the United States, remains a fixture of the Mabel Smith Douglass Library.

Prior to the founding of the Women Artist Series, Douglass students participated in events and installations on the campus. By the 1950s, there was no shortage of women artists at Douglass, just a shortage of female role models. According to Women Artist Series founder Joan Snyder in a 1992 article, “the faculty consisted of some old blood, some new blood–all male blood. The irony of this was inescapable for the MFA program which was on the Douglass Campus, a women’s college never having had a woman teaching a studio course. These were the years right before the dawning of the women’s/feminist art movement.” Snyder is one of the many Douglass graduates who eventually got MFAs from the co-ed master’s program. Another is Letty Lou Eisenhauer, who graduated from Douglass in 1957 and Rutgers in 1962. Eisenhauer is one of the earliest students who gained prominence in the art world particularly in performance art. She first appeared in Kaprow’s Spring Happening, which subverted an old Douglass tradition of the Maypole dance. Eisenhauer continued performing in Happenings through the sixties while building her own Pop Art career. While attending the MFA program from 1961 to 1962, she also acted as the department secretary.

Loretta Dunkleman (DC ‘58) would go on to get her MFA from Hunter College in New York City and, like Eisenhauer, became a prominent figure in the New York art scene. Dunkleman was also important in the feminist art movement of the seventies. In 1972, Dunkleman co-founded A.I.R. Gallery, the first all–female artist-run gallery in the United States. At this time, the need for female-exclusive spaces, especially in the arts, began being filled. Especially in New York, many of the women who initiated these changes were Douglass women, once again illustrating the symbiotic relationship between the New York and New Jersey art scenes. Dunkleman sat on the board of the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists with fellow alumna Joan Snyder in 1972. The Ad Hoc Committee was founded two years prior as a coalition of feminist artist groups such as Women Students and Artists for Black Liberation, Women Artists in Revolution, and Art Worker’s Coalition. The group’s primary purpose was to protest under-representation at the Whitney Museum’s Annual Exhibition. While Snyder and Dunkleman both sat on the Ad Hoc Committee, a prompt was sent to 800 artists asking about their experiences with gender-based discrimination. The result was a series of letters called “the Rip Off File,” which was displayed at the Douglass Library the following year. The exhibit was in good company, as the space showed the work of 31 artists during the 1973-1974 school year.

“The Rip Off File,” was displayed at the library as part of the newly established Women Artists Series. This ongoing series began as a result of Snyder’s frustration with the marginalization of women in the gallery system. The series was founded in 1971 through Snyder’s collaboration with Douglass librarians, and was a solution to a variety of issues that Snyder, her classmates, and colleagues identified. First, the series provided gallery space to women artists, and secondly the gallery space provided female role models to students. She recounts the story of the series founding in her article “It Wasn’t Neo to Us,” for the Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries. Sandwiched between Ad Hoc and AIR, the founding of the Mary H. Dana Women’s Artist Series is an important part of feminist art history. The series continues to represent the values Mason Gross advocated as the president of Rutgers. It integrates art into academic space, uplifts the community beyond New Brunswick, and showcases diversity in artistic voice. Thanks to Snyder and ongoing support of the Center for Women in the Arts and Humanities, Rutgers University Libraries, and Douglass College, the Mary H. Dana Women Artist Series maintains these values at Douglass today and reminds us of its history as the place for women in radical art.

More information can be accessed at The Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA). Online at: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/scua.

The Miriam Schapiro Archives, https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/scua/women-artists-about houses materials about female artists, educators, and much more.

About the Author:

Rachel Ferrante, DRC ‘19, has a degree in American Studies from Rutgers and currently serves as the Historic and Architectural Preservation intern for Histoury, a subsidiary of On Location Tours a nonprofit heritage tourism company.

Works Consulted:

Beryl K. Smith, “The Mary H. Dana Women Artists Series: From Idea to Institution,” The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries, 54.1 (1992), p. 4-5.

Hendricks, Geoffrey. Critical Mass: Happenings, Fluxus, Performance, Intermedia, and Rutgers University, 1958-1972 (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2003).

“History.” Mason Gross School of the Arts, https://www.masongross.rutgers.edu/about-us/.

Joan Snyder, “It Wasn’t Neo to Us,” The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries, 54.1 (1992), p. 34-35.

“Mary H. Dana Women Artists Series.” Rutgers University Libraries, Exhibits. Online

https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/exhibits/dwas

Marter, Joan M., and Simon Anderson. Off Limits Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde, 1957-1963. Newark Museum, 1999.

Marter, Joan M. Women Artists on the Leading Edge : Visual Arts of Douglass College New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2019.

Olin, Ferris., and Joan M. Marter. Artists on the Edge : Douglass College and the Rutgers MFA New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 2005.

Schmidt, George P. Douglass College; a History. Rutgers University Press, 1968.

Archival Sources:

Inventory to the Records of the Rutgers University Office of the President (Mason Welch Gross), 1936, 1945-1971 (RG 04/A16), Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

Inventory to the Records of the Dean of Douglass College (Group I), 1887-1973 (RG 19/A0/01), Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

My father, Louis Till, was a freshman, engineering major, in the fall of 1918. He was born in January 1900. He was raised in New Brunswick.

I found your article intriguing and informative.

I have a sterling silver medal with the inscription RIFLE, that confirms my father’s marksmanship at Rutgers, as well as other memorabilia and photographs relating to my father’s time at “Dear Old Rutgers.”

I am 75 years of age, practicing law in San Jose, CA.