Originally posted on the Books We Read blog.

Books have been banned, challenged, censored, or even burned by organizations, schools, and parent organizations for a number of reasons. What defines a banned or a challenged book? A banned book is one that has been removed from the shelves completely. Books that have been challenged are an attempt by a person or group to remove or restrict materials to protect others. Books have been challenged for being considered “sexually explicit,” for having “offensive language,” or for being “unsuited to any age group.” At Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives, we have a collection of over 53,000 books, pamphlets, and broadside. With that many books in our collections, we have a number of books that have been banned over the years. Here are a few books from our collections and why they were banned.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been a controversial book since its first printing in 1884. The Concord Public Library banned the book in 1885 for its “coarse language” and today it continues to be challenged/banned for its use of racial stereotypes and slurs.

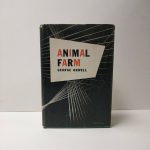

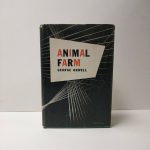

Animal Farm by George Orwell

Animal Farm by George Orwell

The book was completed in 1943 but could not find a publisher because of its criticism of the USSR, an important ally during WWII. It was finally published, but was banned in the USSR and other communist countries. The book is still banned today in North Korea, and censored in Vietnam.

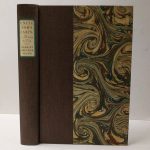

Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England by John Milton

Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England by John Milton

John Milton wrote Areopagitica in 1644 to argued for the freedom of speech and expression and opposing the licensing and censorship by the English Parlament.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

According to The Guardian, Brave New World is among the top ten books Americans want banned for its contempt for religion, marriage and family, as well as its references to sex and drugs.

Candide by Voltaire

Candide by Voltaire

Candide was another book which was banned upon its release in 1759 by the Great Council of Geneva and the administrators of Paris. It was later banned in the United States in 1930 for obscenity.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto was banned by many countries around the world to prevent the spread of communism.

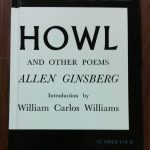

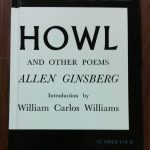

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

The poem was part of a 1957 obscenity trial for the topics of illegal drugs and sexual practices. A California State Superior Court ruled that the poem was of “social importance,” and dismissed the case.

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

This poetry collection was considered obscene upon its release in 1855. Libraries refused to buy the book, and the poem was legally banned in Boston in the 1880s and informally banned elsewhere.

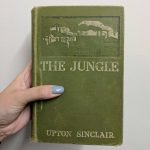

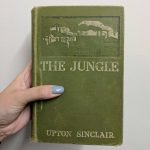

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

The Jungle was banned in a number of counties around the world including Yugoslavia, South Korea and East Germany. The Nazi party in Germany actually burning the book in 1933 because of the socialist views.

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Of Mice and Men is often found on the American Library Association’s list of banned books for its use of racial slurs, profanity, vulgarity, and offensive language.

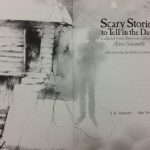

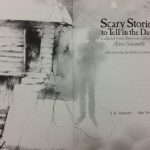

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz

This series of children’s books based on folklore and urban legend is on the American Library Association’s list of most challenged series of books from 1990–1999 and is listed as the seventh most challenged from 2000–2009 for violence.

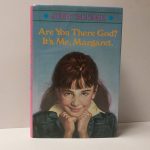

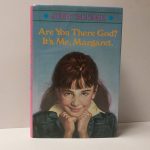

Tiger Eyes and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret both by Judy Blume

Tiger Eyes was challenged for its depiction of violence, alcoholism, and discussion of suicide. Whereas, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was challenged for sexual references and alleged anti-Christian sentiment. Judy Blume is the second most challenged author, only following Stephen King. Her books are often challenged by parents and religious groups for her writings about puberty, masturbation, birth control, and teenage sexuality.

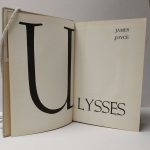

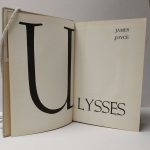

Ulysses by James Joyce

Ulysses was banned in the U.S. until 1934 because of obscenity. That would be this 1924 fifth printing of the first edition of Ulysses owned by Selman Waksman.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was banned in the American south preceding the Civil War for holding pro-abolitionist views and arousing debates on slavery.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Candide by Voltaire

Candide by Voltaire