by Gary A. Rendsburg

Blanche and Irving Laurie Chair in Jewish History

Department of Jewish Studies

see parts 1 and 2 here and here…

At this point, it is worth recalling that virtually all of the texts in the Robison Collection always have been known to the Jewish tradition (Bible, etc.) – notwithstanding the occasional appearance of an interesting variant reading in our documents. Hence, their heuristic value lies more in revealing how a remote Jewish community transmitted the sacred texts for centuries in manuscript form – long after the vast majority of Jewish communities transitioned to the printed book (with the exception of the liturgical reading of handwritten Torah scrolls in the synagogue).

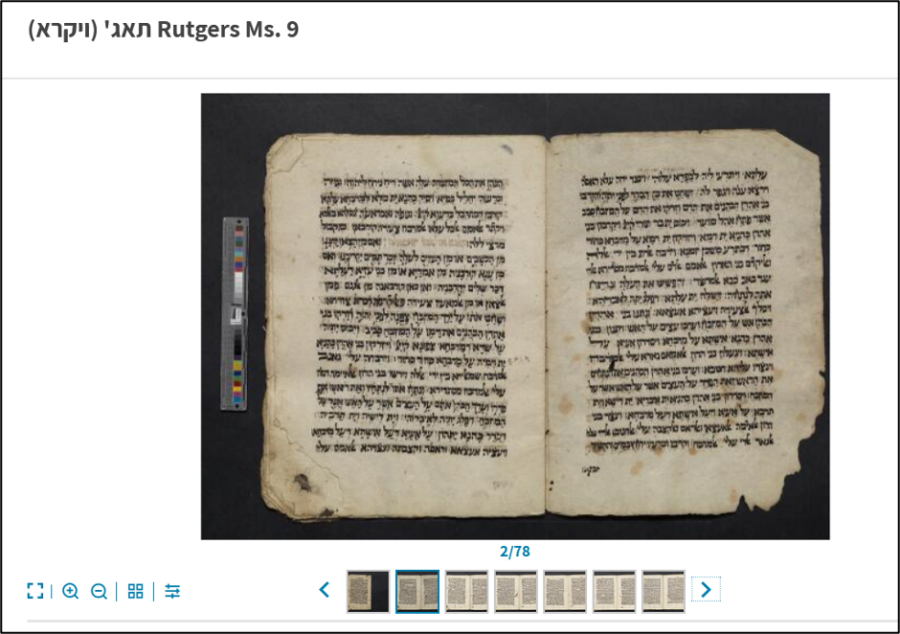

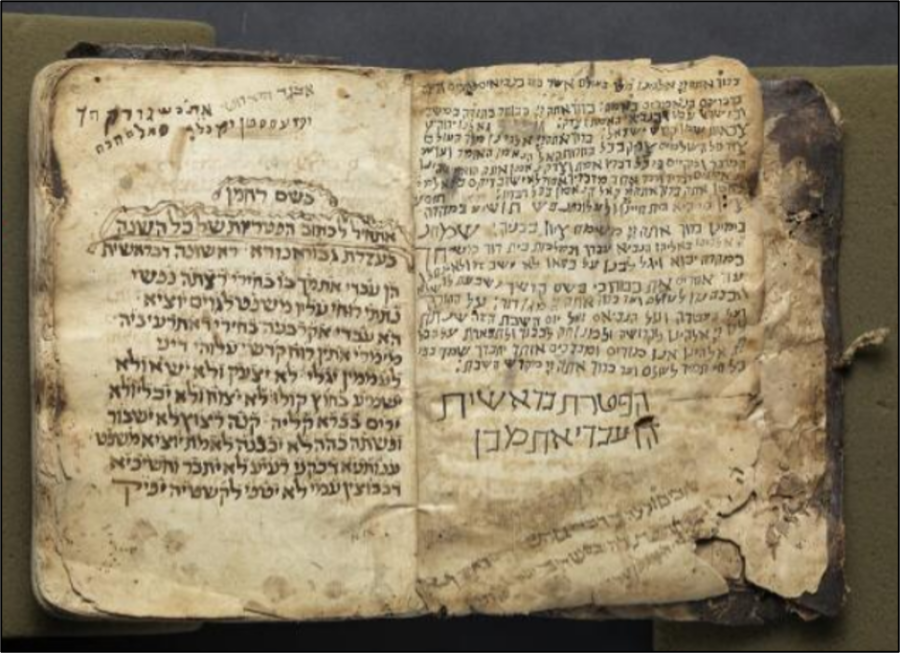

There is more, though, from the realm of popular knowledge (for lack of a better term). Almost all of these documents contain the jots and tittles of various users throughout the ages, as illustrated here, the start of MS 17 (dated to the 17th century), which contains the haftarot, or prophetic portions, read in the synagogue each Shabbat.

The liturgical text proper starts about one-third of the way down the left page (fol. 1r). Above that, framed in decorative squiggles, the original scribe wrote, “in the name of the Merciful One, I shall begin to write the haftarot for the entire year, with the help of the divine, beginning with Genesis” – a nice touch.

Near the top of the page, however, a later user of the text has doodled the alphabet and some random letters: can you imagine using a sacred text in such fashion?!?! But such was life in Yemen, with writing materials at a premium.

And then on the right side, which is actually the inside front cover, another later individual, with a less-than-professional hand, has written the blessings to be intoned before and after the recitation of the biblical text.

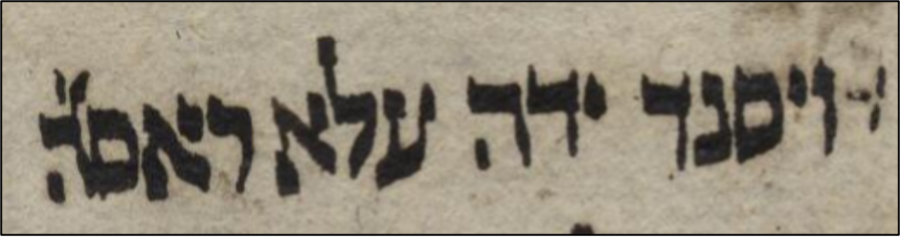

Below that appears in large letters, once again in a less-than-professional hand, the words “haftarah of Genesis” (on the first line) and “behold my servant, whom I uphold” (on the second line), the opening words of Isaiah 42:1 (though with the penultimate letter incorrectly formed and then the penultimate letter not actually part of the biblical text). One gains the impression that a lad, still in the process of learning how to write Hebrew, has inscribed these two lines.

Finally, at the far bottom of the page, is another set of lines, not part of Jewish liturgy, as far as I can determine – though I will leave for those more expert than I to decipher and explicate these words.

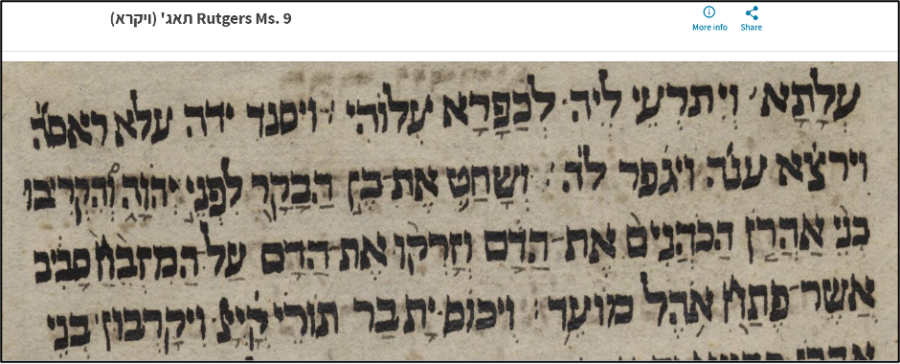

If we return to the actual biblical text on fol. 1r, for those who can read Hebrew and Aramaic, I would point out the following, very technical information. First, note that the Hebrew original is accompanied by the Aramaic translation (known as Targum Jonathan, in this case); and secondly, the vowels which accompany the consonants are the supralinear Babylonian ones (a system distinct from the better known Tiberian sublinear vowel markings). Re the first: note that in Yemenite synagogues, the biblical text was chanted both in Hebrew and in Aramaic translation, so that the reciter of the text could simply read straight through, using a manuscript such as ours. Re the second: the pronunciation of Hebrew amongst the Yemenite Jews is closer to the ancient system employed in Babylonia (than in the land of Israel), hence, their continued use of this less well known vocalization system.

So much to learn from our inspection of a single photograph! Once again, multiply this exercise by the hundreds, nay by the thousands, and one gets an idea of the true value of our precious Robison Collection of Hebrew Manuscripts – now available to the world at-large through the Ktiv website!

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Sonia Yaco and the staff of SCUA for their ongoing assistance with this project, as well as my former research assistant, Annabelle (Nonnie) Sinoff (class of 2021), who provided all manner of both academic and logistical support throughout this process.