Happy 2020! We’re kicking off the new year with this piece by Emily Crispino, a graduate student in the Library and Information Science Department at Rutgers’ School of Communication and Information. During the fall 2019 semester, Emily was a public services intern in Special Collections and University Archives. In this position she assisted researchers at our busy reference desk and researched and responded to a variety of inquiries from around the world related to New Jersey history and genealogy through our virtual reference service.

~~

While I cannot claim enough knowledge to call myself an herbalist, my shelves full of dried plants would seem to qualify me as an herbal enthusiast. I brew a yearly elderberry syrup to ward off winter colds, drink teas for just about every ailment, and occasionally concoct something new after consulting my personal library of herbals. Written by everyone from New Age gurus to a former botanist for the USDA, these books outline the medicinal properties of plants, accompanied by physical descriptions, dosage information, and recipes for preparations such as salves and tinctures. Often, photographs or botanical sketches accompany each entry.

Ideas about health and medicine have changed a great deal over the last 300 years, but the herbal format has remained largely the same. Special Collections and University Archives holds many examples of historical herbals, including two that I would like to examine in this post. The first is a 1798 edition of Nicholas Culpeper’s English Physician and Complete Herbal, first issued in 1652. The second is A Curious Herbal by Elizabeth Blackwell, a 1751 edition of a work first published in 1737. Just like my New Age gurus and government workers, Culpeper and Blackwell approached herbalism from entirely different points of view. Yet both books are written in the service of healing, designed to help people help themselves.

~~

Nicholas Culpeper was a character to say the least, boasting a colorful career as an herbalist, astrologer, and sometime soldier against the King during the English Civil War. A non-conformist both in medicine and politics, Culpeper frequently received criticism from the more traditional physicians of his day. In 17th century London, the medical profession was dominated by the Royal College of Physicians, whose Censors bestowed licenses upon those whom they deemed worthy to practice. Culpeper loudly criticized their methods and accused them of overcharging for their services, making medical care inaccessible to the poor. In his own practice, he saw patients regardless of their financial status and examined them holistically before diagnosing and treating them. (2)

Elizabeth Blackwell’s herbal was born of more personal motivations. After her husband, a physician, was thrown into debtor’s prison, she began work on A Curious Herbal as a means to raise the funds to free him. While Blackwell was a skilled botanical illustrator and may have had some training as a midwife, she does not appear to have been an herbalist in the strict sense. The medical information in her book was primarily derived from another herbal, the Botanicum Officinale, with the permission of its author. Nevertheless, Blackwell spent years carefully sketching, engraving, and coloring plates of medicinal plants for her herbal, supported in her endeavor by a number of respected physicians and apothecaries. A Curious Herbal received significant praise and sold well, successfully paying her husband’s debts and securing his release. (1)

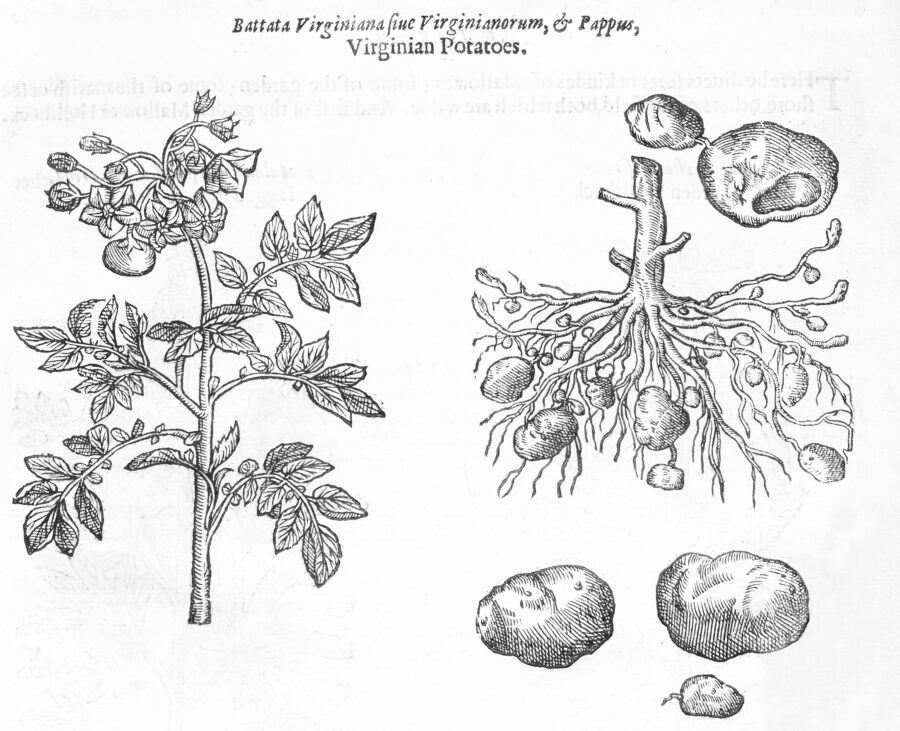

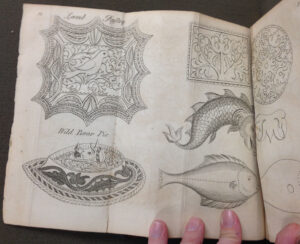

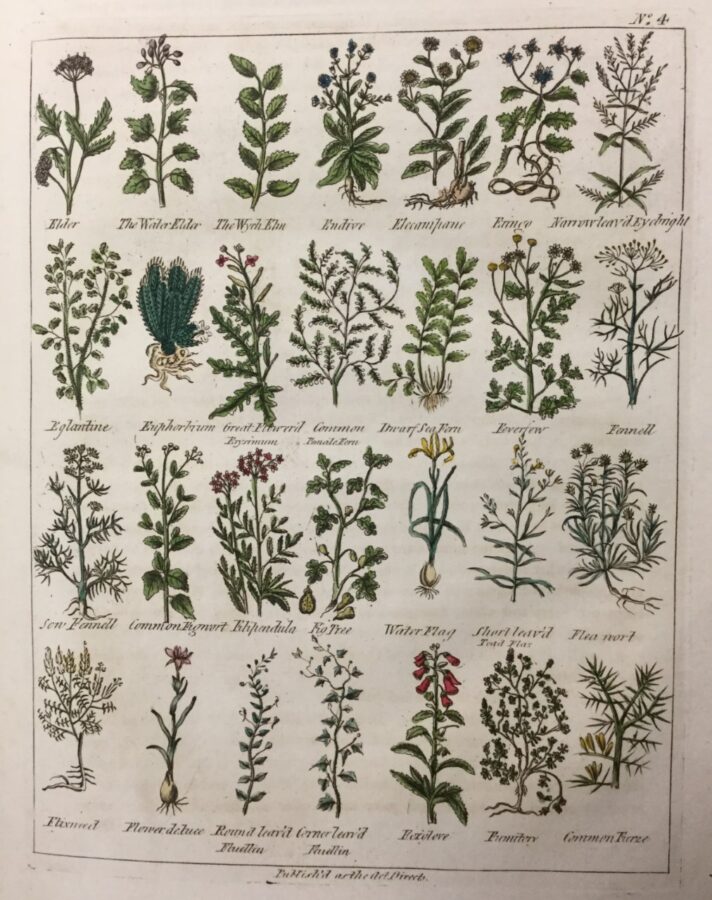

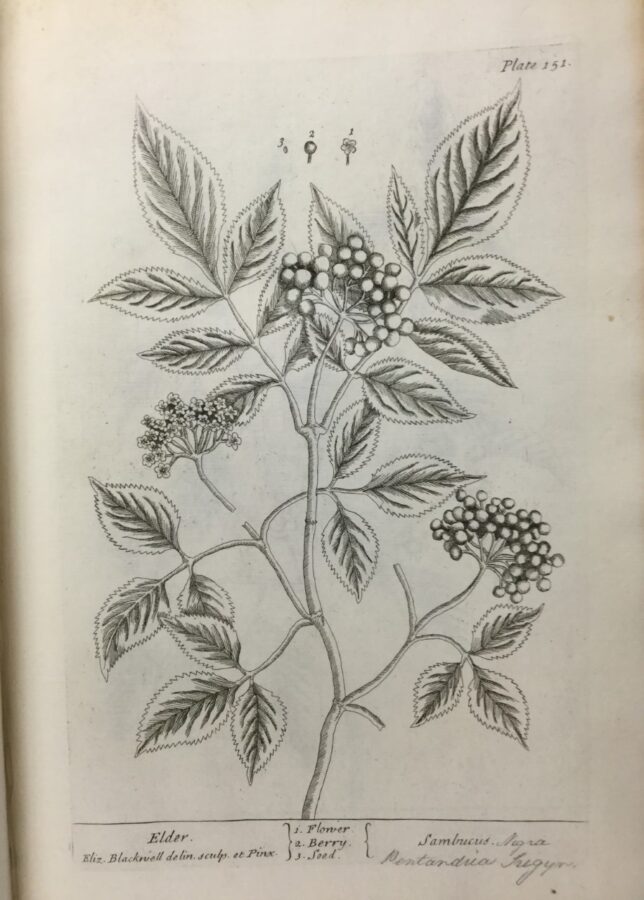

The differing backgrounds of Culpeper and Blackwell are clearly reflected in their herbals. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal contains a great deal more text than A Curious Herbal, including information on common ailments and preparing medicines in addition to his alphabetical directory of herbs. Sparing no words when explaining their properties, Culpeper’s physical descriptions of plants are surprisingly inconsistent, and he entirely neglects to describe those that he believes are commonly known. “I hold it needless to write any description of this,” he explains, referring to the elder tree, “[since] any boy that plays with a potgun, will not mistake another tree instead of elder.” The missing descriptions are not well supplemented by the illustrations, which are tiny and crammed onto designated pages.

Even these are 1798 additions, with the first edition of Culpeper’s herbal including no images at all. A Curious Herbal, on the other hand, is built around Blackwell’s illustrations. These full-page plates depict seeds, roots, and flowers in addition to the main bodies of the plants and are detailed enough to help readers identify them in the wild.

The images in the first edition were colored as well, adding to their accuracy. At the same time, the accompanying text is minimal, lacking the depth of medical information contained in Culpeper’s herbal. There is also no distinguishable order to the entries, requiring one to flip through the entire book to find information on a specific plant.

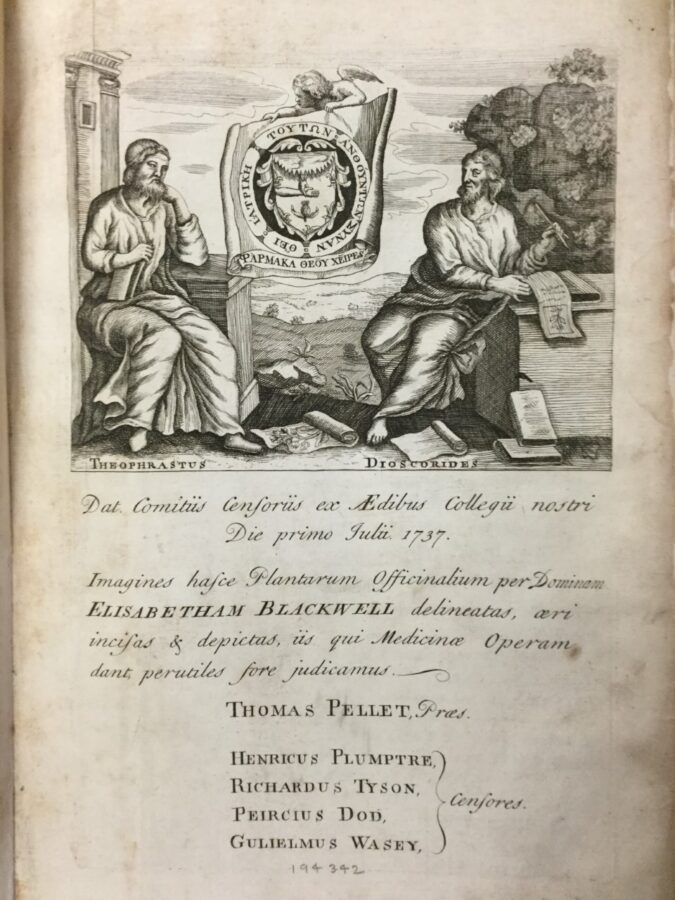

Of particular interest is the front matter of A Curious Herbal, revealing a further difference between the two books. A large illustration of ancient Greek botanists Theophrastus and Dioscorides precedes the official endorsement of the College of Physicians, signed by its then-president and Censors.

The recommendations do not end there, as a subsequent page proclaims the approval of nine more physicians and “Gentlemen.” This reception to Blackwell’s herbal could not be more unlike that of Culpeper’s, which, despite its immense popularity, received no such praise from the College. The College’s opinion of Culpeper may be summed up in a comment from member William Johnson, who proclaimed one of his works “a paper fit to wipe one’s breeches withal.” (2)

New editions of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal are published to this day, testifying to the enduring attraction of traditional medicine and home remedies. Elizabeth Blackwell too is slowly gaining recognition, and a calendar featuring her work has been released for 2020. Although they came to herbalism from very different backgrounds, those who come to it today are no less diverse. Alongside countless modern additions to the body of herbal literature, the centuries-old works of Culpeper and Blackwell have continued to inspire new herbalists—and herbal enthusiasts.

References

1 Madge, B. (15 April 2003). “Elizabeth Blackwell—the forgotten herbalist?” Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2001.00330.x

2 Wooley, B. (2004). Heal thyself: Nicholas Culpeper and the seventeenth-century struggle to bring medicine to the people. New York, NY: HarperCollins.