By Helene van Rossum

Helene van Rossum is a Dutch-born researcher and writer, who worked at SC/UA as public services and outreach archivist in 2016-2018

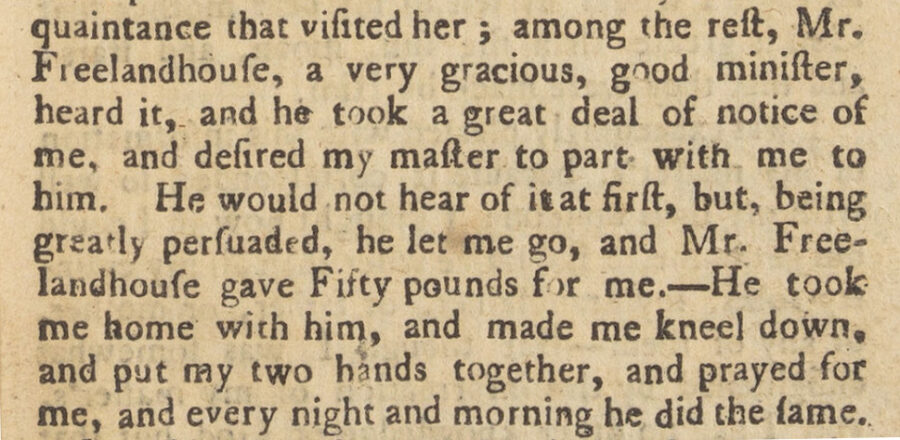

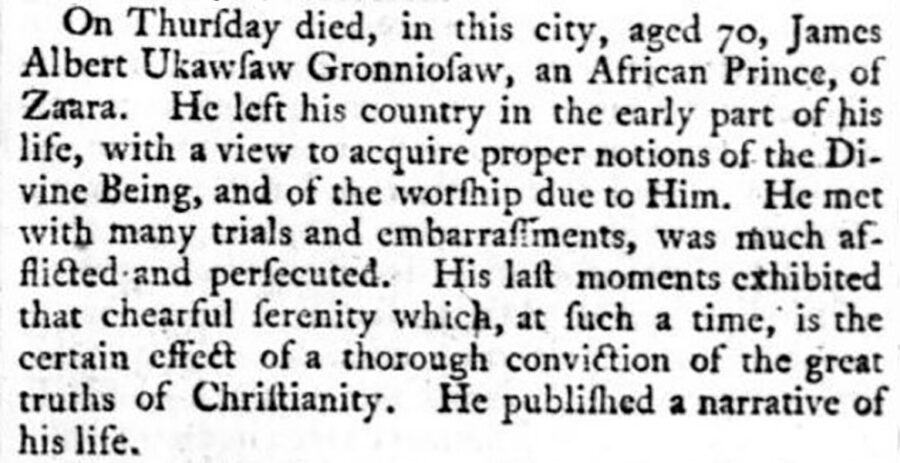

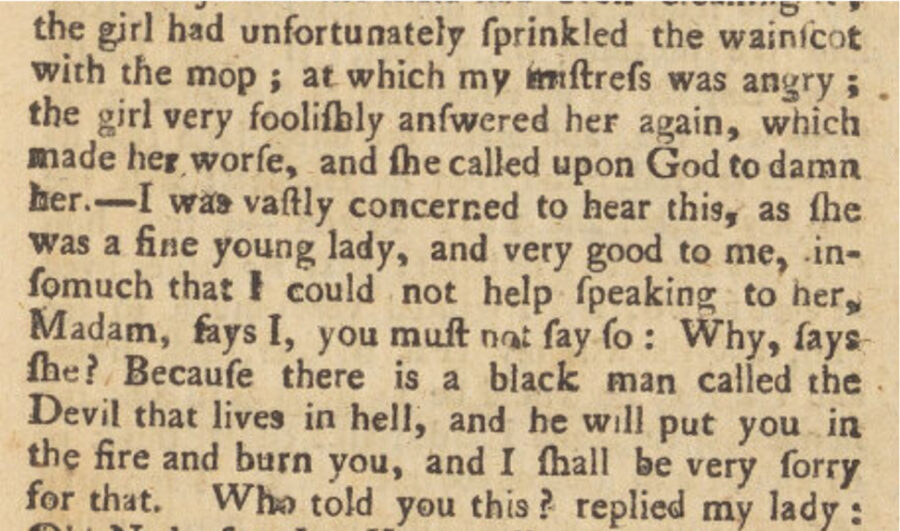

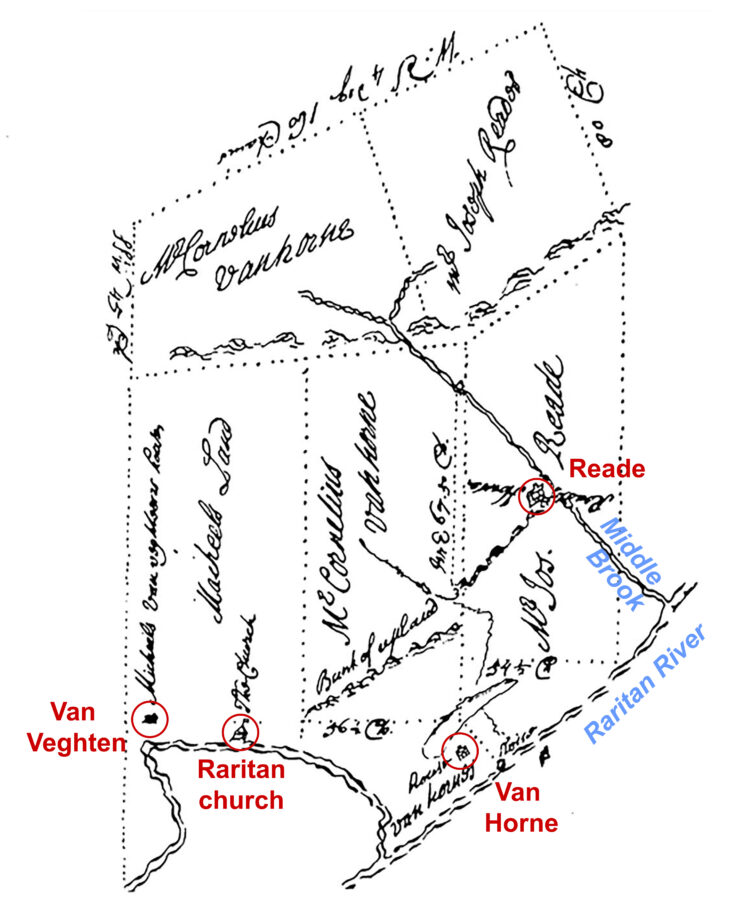

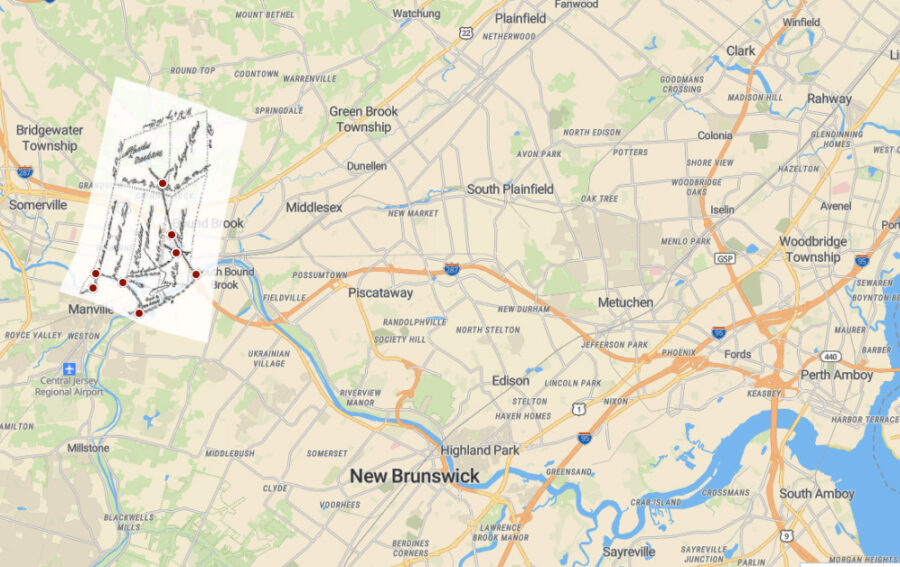

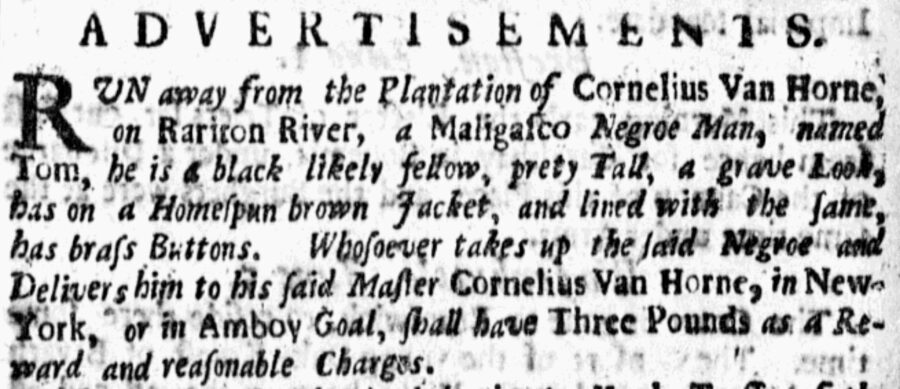

In our previous posts we talked about Dutch Reformed minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen (1691–c. 1747) as well as his enslaved servant Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, whom he purchased from his parishioner Cornelius Van Horne and converted to the Calvinist faith. This post and the next will be about the fate of Frelinghuysen’s five sons, who all became ministers themselves, but died within a short time.

The Frelinghuysen family

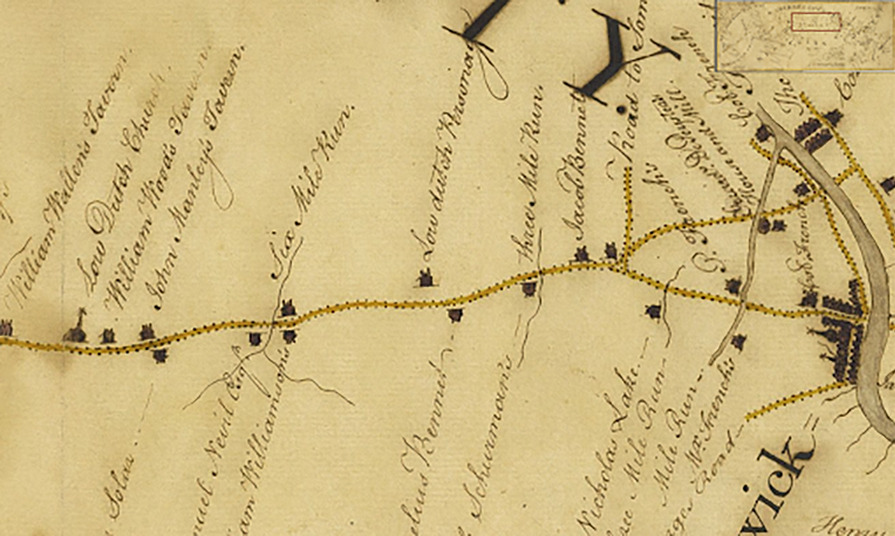

Not too long after Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen became the new minister of the Dutch congregations of Raritan, Three Mile Run (including New Brunswick), Six Mile Run, and North Branch he married Eva Terhune from Flatland, Long Island.1 They were given a farm near the Three Mile Run church to live in, and the first child, Theodorus Jacobus Jr, was born in 1723. His four brothers Johannes (John), Jacobus, Ferdinandus, and Henricus were born between 1727–1735 and two more girls, Margaret and Anna followed in 1737 and 1738.

We do not know exactly when Frelinghuysen purchased Gronniosaw in the 1720s, but the young African must have known all the children since they were very little. He was there when Theodore Jacobus Jr. left for the Netherlands in 1743 to study, be licensed, and ordained, and then answered a call to Albany, NY. He saw Johannes leaving for the Dutch Republic too in 1747, the year when Theodore Sr, fell ill. He helped care for the minister, who told him on his deathbed that he had freed Gronniosaw in his will.

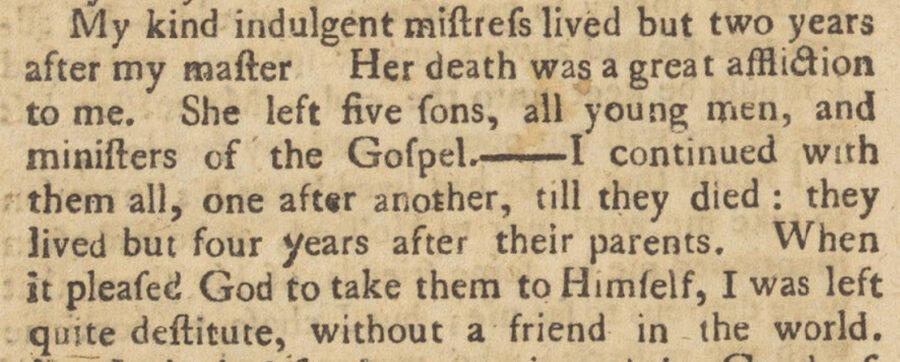

Though a free man, Gronniosaw decided to stay to serve the widow. According to his Narrative he was heartbroken when Eva Terhune died, either shortly before or after her son Johannes’ return. The three younger brothers were between 15 and 20 years old at the time, their sisters 11 and 12.

Johannes Frelinghuysen and Dina van den Bergh

After Eva’s death, according to his Narrative, Gronniosaw subsequently served her five sons, until they all died too. He may have started with Johannes. The young man had received a call from the parishes of Raritan (Somerville), North Branch (Readington), and Millstone (later Sourland, then Harlingen), written on May 18, 1749.

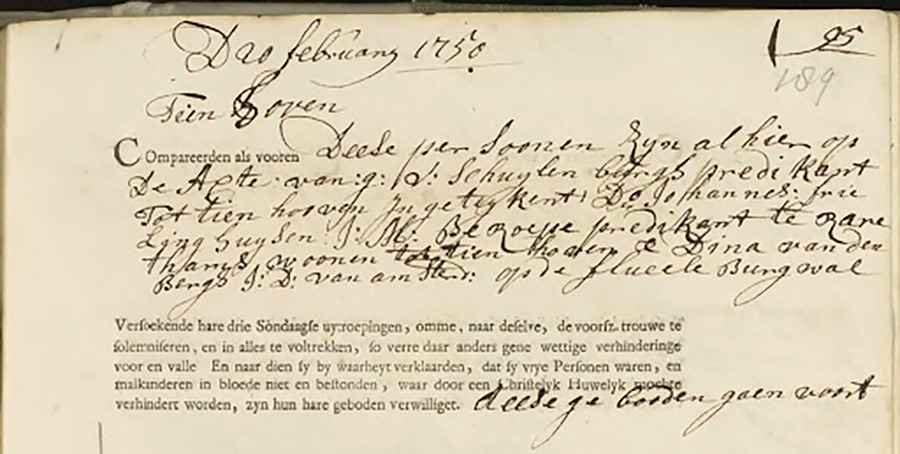

When Johannes received the letter he was living in the parsonage of the Dutch pietist minister Gerardus van Schuylenburg in Tienhoven. Van Schuylenburg must have introduced him to the pious merchant’s daughter Dina van den Bergh in Amsterdam, with whom he had been corresponding. When John asked her in September to marry him and come with him to serve the parishes in the Raritan Valley the young woman was stunned.

There are many stories about Dina, who signed her letters as Dina Van Bergh. She was so pious that she had refused the dancing lessons her parents wanted her to take. As a teenager she was said to have stopped her father and his friends playing cards for money by starting to pray when she walked into the room. She kept a religious journal in 1746-1747 and in 1749, which has been translated into English. In the last part she documented her struggles to accept John’s proposal under the heading “Some few notes on how my heart, through hidden instructions, was prepared and afterwards bent by the Lord towards marital relations with the Rev. Mr. Johannes Frielinghuysen, minister at Raritan in New Netherland.”

Life with John in the parsonage

Dina hoped to send Johannes to New Jersey and fetch her one or more years later, but when a storm prevented him from leaving, she felt it was a sign from God to join him. According to local lore, the ship in which the couple finally sailed almost did not make it to the New World because of a terrible storm that caused a leak. In one story Dina had her chair tied to the mast of the ship and prayed throughout the ordeal, until the winds stilled. A swordfish was later found to be wedged in the crack, stopping the leak.

Another story tells us the ship carried bricks for the new parsonage in Raritan to be built in by the three congregations. Constructed in 1751, the sturdy brick house is presently known as the “Old Dutch Parsonage” in Somerville. Before it was moved to its present location, according to a description of the building the parsonage had slave quarters and two wide fire-places and an oven in the basement. Though a free man, Gronniosaw would have slept in the basement, along with the enslaved servants Dina would refer to in a letter to Henricus in November 1754, published along with her diary.

The couple had two children; Eva (born 1751) and Frederick (born 1753), the ancestor of the Frelinghuysen family of Somerset County. They were only toddlers when their father unexpectedly became sick and died in September 1754 during a trip to Long Island to attend a meeting of the Coetus (an assembly of Dutch ministers and elders). Dina went to fetch the body herself. The story goes that when the boat carrying the coffin pulled into the dock it could not come close enough to debark. Dina then ordered the coffin to be used as a bridge across the gap, telling the passengers “‘Tis only a shell, his spirit is gone. Cast it across.”

Marriage to Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh

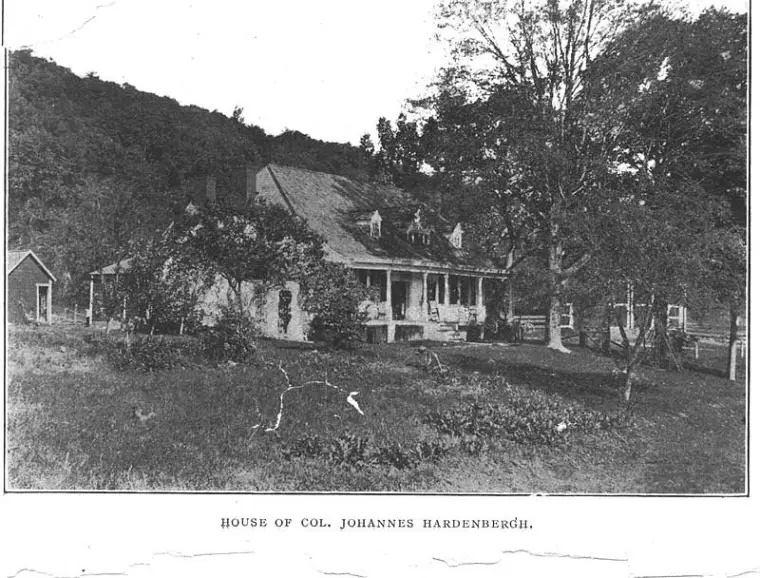

The parsonage had also been used for teaching young aspiring Dutch ministers at the parsonage, who boarded there. One of Johannes’ students was future president of Queen’s (Rutgers) College Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh from Ulster County, NY, son of Johannes Hardenbergh (1706-1786), who lived in a large house called “Rosendale” in what was still Hurley at the time. Jacob was eighteen when Johannes died and, as a boarder, must have known Dina well. Although he was probably aware that she wanted to go back home he proposed to the eleven years older widow to marry him instead. ”My child, what are you thinking about?” she reportedly exclaimed.

Unwilling, Dina continued to make preparations for her trip home. But when a storm prevented her from leaving, she felt it was another sign from God. They moved in with Jacob’s parents in Ulster County, where he finished his studies. Formally called to be Johannes’ successor, Jacob married Dina two years later in Raritan and the family moved back into the Dutch parsonage. A dress that was passed down though the family as her wedding dress is kept at Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives.

Why Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh did not go to the Netherlands to be licensed and ordained, like Theodore Jr., and John Frelinghuysen before him, we will hear in the following blog post: The Terrible Fate of the Frelinghuysen Brothers, Part 2: Ulster County.

1 I am following genealogical findings published in Barbara Terhune, “The True Parents of Eva (Terhune) Frelinghuysen and her sister, Annetje (Terhune) Schuurman,” New Netherlands Connections, vol. 12, no. 3 (2007). An early version can be found online here

Contents of this blog post were shared in a presentation “’That class of people called Low Dutch,’ African Enslavement Among the Dutch Reformed Churches of Ulster County and New Jersey’s Raritan Valley,” by Helene van Rossum and Wendy Harris at Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, NY (April 7, 2018)