By Stephanie Crawford

Over the past two months, I have been conversing with Dr. Glyn Thompson, a retired art history professor from Leeds University, in regards to our holding of early twentieth-century pottery company trade catalogs in the Sinclair New Jersey Collection. His research question is a fascinating one: Did Marcel Duchamp create the iconic 1917 ready-made Fountain? Dr. Thompson argues that Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was the creator of Fountain by supporting a counter narrative of the creation of one of the most important works of art in the twentieth century.

The art history Fountain myth goes like this:

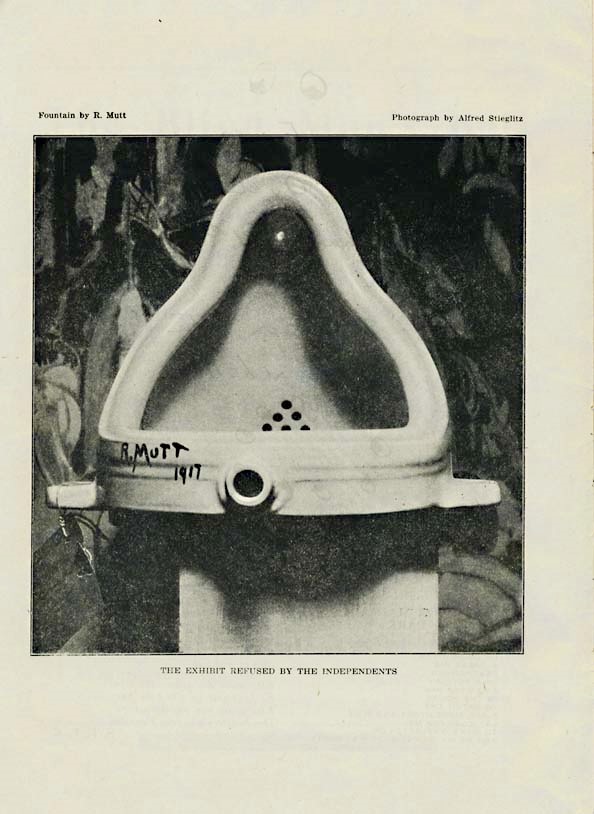

Duchamp began creating ready-mades in 1913, when he chose a spinning bicycle wheel as a work of art. Ready-mades are just as they sound: commercially manufactured everyday items. Part of the allure of the ready-made is in the artistic choice of the object; the other is in the reading of the form in an attempt to find meaning. In 1917 Duchamp bought a urinal from the J. L. Mott Pottery Company which had a showroom in the Upper West Side. He turned the urinal on its side, and signed it “R Mutt 1917”. R Mutt, or the full Richard Mutt, is a word play on the name Mott and also the cartoon characters Mutt and Jeff. Duchamp then submitted the urinal to the annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, of which he was a member. The society was formed by artists who were subverting the typical exhibition favoritism of other art clubs by accepting anything that an artist submitted. Artworks were to be hung/displayed alphabetically. Duchamp challenged the society’s liberal take on art and artists, pushing to see if they would accept anything as a work of art. Members of the society were appalled by the submission, and refused to display it, hiding the urinal in a back room. After the exhibition, Duchamp resigned from the society because of the conservatism. Alfred Stieglitz photographed the urinal at Gallery 291 and ultimately the original urinal was lost.

With Fountain, Duchamp was pushing the boundaries of the definition of art and authorship in asking questions like: “What is a work of art? Who gets to decide, the artist or the critic? Can a work derive from an idea alone, or does it require the hand of a maker? These questions strike at the core of our understanding of art itself.” Is it art because it’s made by an artist? What is the difference between a tea cup and a sculpture that looks like a tea cup? Why are functional items not art?

Other than several articles published in Blind Man issue number 2 from 1917, there was little to nothing published about the urinal, including the identity of Richard Mutt. In the 1950s and 1960s Duchamp took credit for, and authorized replicas to be made of The Fountain. This art history narrative of the creation and eventual attribution of Fountain to Duchamp serves to fuel the status of Duchamp as a misunderstood, avant-garde genius whose whole life was art, creating this myth and mythical artist that has ignored facts and obvious faults.

But it doesn’t seem to matter to art history if Duchamp created Fountain. Stated rather succinctly in a 2017 Artsy article: “But to try and establish the true authorship of the Fountain is exactly the kind of quixotic undertaking that would have had Duchamp in stitches. Let’s take a moment to recall that Monsieur Duchamp took a urinal, turned it upside down, signed it ‘R. Mutt,’ and submitted it to a salon; the pursuit of truth was decidedly not his quest.” Ignoring the questionable authorship of one of the most important artworks of the twentieth century because Duchamp is your favorite artist is a quixotic and fundamental misunderstanding of the intersection of feminism and art history. I’m willing to look past Joseph Beuys’ lies about his origin story in order to see his artistic merit because at least his ideas were original. Women artists deserve more than to be regulated as the kooky sidekicks, the sexy muses, or the martyred wives whose work gets stolen by their male counter-parts. Why is Marcel Duchamp a genius and Elsa a kook?

The evidence that Fountain was chosen and submitted by Marcel Duchamp is largely based on statements made by Duchamp in the 1950s and 1960s. Dr. Glyn Thompson is attempting to interrupt the Artist-as-genius narrative with his research into the Trenton Pottery Company. The counter-narrative he produces is a convincing argument that one of the greatest works of art was, in fact, created by a woman. More information can be found in Thompson’s eBook Duchamp’s Urinal? The Facts Behind the Façade.

The following are Thompson’s core arguments:

1.) In a 1917 letter to his sister, Suzanne Duchamp, Marcel writes:

“April II [1917] My dear Suzanne- Impossible to write- I heard from Crotti that you were working hard. Tell me what you are making and if it’s not too difficult to send. Perhaps, I could have a show of your work in the month of October or November-next-here. But tell me what you are making- Tell this detail to the family: The Independents have opened here with immense success. One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture it was not at all indecent-no reason for refusing it. The committee has decided to refuse to show this thing. I have handed in my resignation and it will be a bit of gossip of some value in New York- I would like to have a special exhibition of the people who were refused at the Independents-but that would be a redundancy! And the urinal would have been lonely- See you soon, Affect. Marcel”[emphasis mine]

The letter is translated and published in Francis Naumann’s 1982 article, though Thompson observes that in footnote 18 Naumann is confused as to why Duchamp would write about this woman friend, refusing to acknowledge that it may be true. The letter is housed in Jean Crotti’s Papers at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

2.) Duchamp could not have purchased the urinal from J. L. Mott Pottery Company because

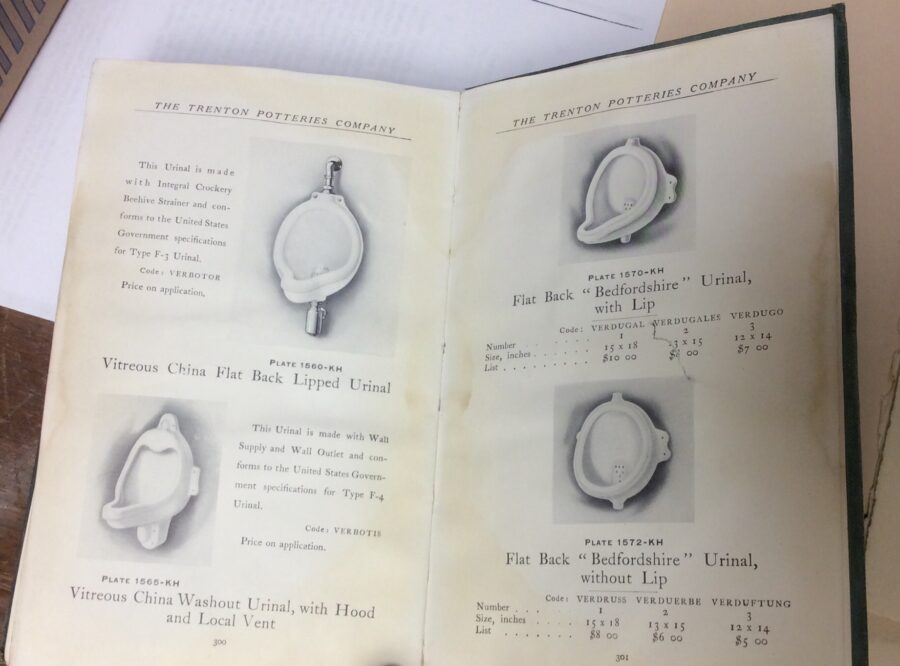

a. You couldn’t just walk in and purchase a urinal from their showroom in New York. You needed a tradesman to be the moderator between you and the company (a practice that is similar today). Additionally, the urinal itself would have been made in and purchased in Trenton, New Jersey, where the factory was. These protocols can be found in the company’s trade catalogs.

b. Mott didn’t make a urinal similar enough to the 1917 image of the urinal.

c. Therefore, the name R. Mutt couldn’t have come from J. L. Mott Company.

3.) The Trenton Potteries Company created the Vitreous China, Bedfordshire No. 1 Flat Backed Lipped Urinal between 1915 and 1921 and it visually matches the Stieglitz photograph of Fountain. This is confirmed both through trade catalogs, and the urinal that is in Glyn Thompson’s personal collection.

4.) Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was a German-born Dada artist living in Philadelphia who was one of the only women who could have created Fountain.

5.) R. Mutt is a Dada play of words on the German word “armut” which translates to poverty or destitution. Poverty of morality was a possible theme of the urinal since on April 6, 1917 the United States declared war on Germany. On April 9th, the urinal reached the exhibition. Also on April 6th, regulations were passed to control movements of German-born individuals on U.S. soil.

It’s difficult to prove without a doubt that Elsa submitted the urinal, choosing it to be a work of art. My initial reaction was, and continues to be: of course she did. Because Elsa WAS Dada. She was Art. She once wore postage stamps as makeup, a birdcage around her neck, and carpet sample rings as bracelets. When she showed up to be George Biddle’s model, she removed her jacket revealing these everyday items and he was shocked. Pictures of her in simple Google searches show a woman making strange gestures and poses for the camera. While Dada performances were meant to make the bourgeois uncomfortable, Elsa made everyone uncomfortable all of the time.

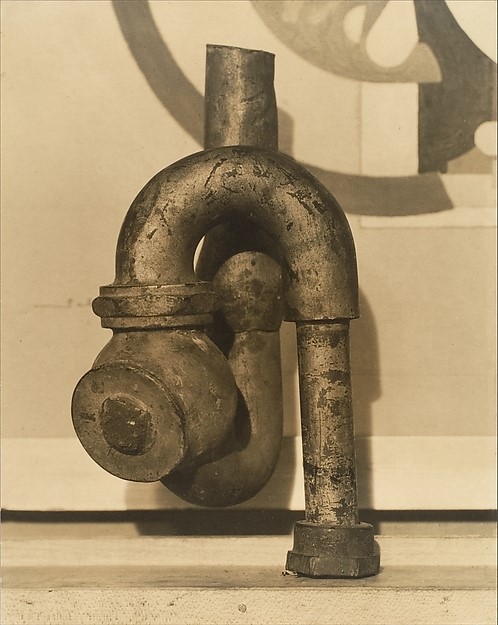

And then there’s God (1917). Previously attributed to Morton Schamburg, God is composed of a twisted drainpipe secured onto a miter box. Readings of the work are tenuous at best, but I like to think that God symbolizes the impotence and mediocrity of “important” men.

Additionally, her poem Astride mimics an orgasm, the climax in a flurry of nonsense words:

“Saddling

Up

From

Fir

Nightbrimmed

Clinkstirrupchink!

Silverbugle

Copperrimmed

Keening

Heathbound

Roves

Moon

Pink

Straddling

Neighing

Stallion :

“HUEESSUEESSUEESSSOOO

HYEEEEEE PRUSH

HEE HEE HEEEEEEAAA

OCHKZPNJRPRRRR

HÜ

/ \

HÜÜ HÜÜÜÜÜÜ

HÜ-HÜ!”

Aflush

Brink

Through

Foggy

Bog

They

Slink

Sink

Into

Throbb

Bated.

Hush

Falls

Stiffling

Shill

Crickets

Shrill

Bullfrog

Squalls

Inflated

Bark

Riding

Moon’s

Mica –

Groin

Strident!

Hark!

Stallion

Whinny’s

In

Thickets.

EvFL”

It is not a stretch then, to think that the Baroness would choose a urinal to send to the Independents exhibition: she used everyday objects in her art, she was keen on word play and bodily functions, and she used herself and her art to make people uncomfortable.

But Elsa tends to get a bad rap. She is often described as: “eccentric”, “crazy”, “visionary”, “strange” and “outrageous”. Like the cult of Frida Kahlo, the Baroness’ sexual exploits and her life take larger precedent than her work: a subheading to a Timeline article states “Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was once arrested for walking down Fifth Avenue in a men’s suit.” In comparison, H.P. Roche describes Duchamp as thus: “When I met Marcel Duchamp in New York in 1916, he was twenty nine years old and wore a halo…From 1911 to 1923 my memories of him as a person are even more alive than my recollections of his work…He was creating his own legend, a young prophet who wrote scarcely a line, but whose words would be repeated from mouth to mouth…” The comparison and hypocrisy is hardly unique to someone who studies women artists, and yet it continues to be infuriating.

It’s doubtful that in Elsa’s archives there will be a diary entry stating “And on this day I mailed a urinal to Louise Norton to be submitted to the Society of American Artists under the name R Mutt, signifying poverty.” Even if there was a diary entry existed, I doubt that it would change peoples’ minds. She was a liar, so you can’t trust her; she was crazy so you can’t believe anything she says; she was just looking for a buck; she was taking advantage of that poor man for her own sake; and all of the other things that people say in order to discredit women who speak out about their experiences. It’s difficult to think of a way to end this post without falling into a pit of despair. Perhaps it is through Dr. Thompson’s efforts to shout into the abyss with his book, his articles, his interviews, and his exhibitions that a change for Elsa will occur. After all, an unwillingness to be quiet is one of our best feminist tools.

____________________________________

[1] Dr. Glyn Thompson, Duchamp’s Urinal? The Facts Behind the Façade (Wild Pansy Press, 2015), 11-13.

[2] Thompson, Duchamp’s Urinal?, 19, 27.

[3] Jon Mann, “How Duchamp’s Urinal Changed Art Forever,” Artsy (May 9, 2017), https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-duchamps-urinal-changed-art-forever (accessed May 30, 2018).

[4] Exhibitions: Challenge and Defy, at Sidney Janis Gallery, 1950, New York. International Dada Exhibition, at Sidney Janis Gallery (15 April-9 May 1953), New York; Retrospective Dada, Dusseldorf (5 September- 19 October 1958). Interview: Text:

[5] Jon Mann, “How Duchamp’s Urinal Changed Art Forever,” Artsy (May 9, 2017), https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-duchamps-urinal-changed-art-forever (accessed May 30, 2018).

[6] The answer is SEXISM.

[7] There is nothing wrong with acknowledging the talent of certain artists, but insistence on the status of the Artist as Genius disallows criticism and unconvincingly simplifies the narrative of their life and work. In addition, modern women artists are almost never described as geniuses. See Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” for a more succinct analysis of the rhetoric associated with male and female artists.

[8] Francis M. Naumann, “Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti,” Archives of American Art Journal (vol 22, no. 4 1982), 8. Written extensively by John Higgs in “The Shock of the New,” Stranger Than You Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 2015), 35-51. Argued by Thompson in Duchamp’s Urinal?, 17-18.

[9] Louise Norton could also be a potential creator of Fountain. In the Stieglitz photograph, the exhibition entry card is still attached, which lists Norton’s address as R. Mutt’s address. Additionally, she wrote an article in Blind Man about R Mutt. To my knowledge, there is no archival collection, book, or article about her art for comparison.

[10] Thompson, Duchamp’s Urinal?, 70.

[11] Additional questions arise, for me, from Duchamp’s story that he simply submitted the piece to the exhibition and that those in charge censored his avant-garde poke at the supposedly liberal Society. The story makes Duchamp seem like he was just a member of the art society, when in fact he played a large administrative role. According to the exhibition catalog for the 1917 exhibition, Marcel Duchamp a director of the Society, and was the director of the hanging committee (See Figures).[1] The catalog can be seen in full here. The hanging committee included George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. Because there were no juries and no prizes in the Society, as long as the artist paid their dues then their work would be hung. In order to prevent hierarchies and favoritism, the pieces were hung alphabetically. This was a very liberal take on annual art exhibition for clubs and societies which often attempted to mark ‘the best” through juries and strategic hangings. But how can you say that those in charge denied your readymade when you were the one who was in charge?

[12] Higgs, “The Shock of the New,” 35.

[13] Tanya Clement, “Poems by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven,” https://jacket2.org/poems/poems-baroness-elsa-von-freytag-loringhoven accessed May 30, 2018. “Papers of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.” University of Maryland, https://archives.lib.umd.edu/repositories/2/resources/22 accessed May 30, 2018.

[14] H. P. Roche, “Souvenirs of Marcel Duchamp”, in Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp (New York: Grove Press, Inc.)