November 11, 2018 is Veterans Day and marks the 100th anniversary of the Armistice that ended World War I. To commemorate this centennial, What Exit? will be featuring letters from Special Collections and University Archives’ Records of the Rutgers College War Service Bureau. This collection features letters from Rutgers students and alumni who served in the First World War, describing their experiences serving in the United States and overseas. Each day between November 1 and 11, Voices of the Armistice posts will share what these Rutgers students from 100 years ago had to say about the moment when peace was declared.

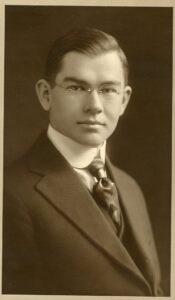

Lauren Archibald (class of 1917), was at the School of Fire in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, when peace was declared. His immediate reaction was “business as usual.”

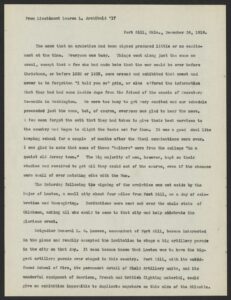

“The news that an armistice had been signed produced little or no excitement at the time. Everyone was busy. Things went along just the same as usual, except that a few who made bets that the war would be over before Christmas, or before 1920 or 1925, came around and exhibited that sweet and never forgotten ‘I told you so’ grin or else offered the information that they had had some inside dope from the friend of the cousin of Secretary So-andSo in Washington. We were too busy to get very excited and our schedule proceeded just the same, but, of course, everyone was glad to hear the news. It was a good deal like keeping school for a couple of months after the final examinations were over. I was glad to note than none of these “balkers” were from a college “in a quaint old jersey town. . .”

The celebration came a few days later.

“The Saturday following the signing of the armistice was set aside by the Major of Lawton, a small city about four miles from Fort Sill, as a day of celebration and thanksgiving . . .

Fort Sill, with its world famed School of Fire, its permanent detail of Field Artillery Units, and its wonderful equipment of French and British fighting material, could give an exhibition impossible to duplicate anywhere this side of the Atlantic.”

The celebration had breathtaking moments:

“. . . almost immediately a battle formation of twenty-five aeroplanes passed over the city. They were followed in fifteen minutes by another squadron. After the ships had passed, they broke ranks and the aviators gave an exhibition of acrobatic flying that is seldom equaled except under actual fighting conditions. They looped and dived, did tail-spins and spirals, falling-leaf, barrel spin, and many more aerial feats impossible to describe.”

This was followed by a grand parade.

“The School of Fire floats were features of the occasion. The department of gunnery had mounted an American 75 on a motor truck and fired salute charges all along the line of MARCH.

One float which did not feature in the parade, however, deserves mention for its clever and original idea. A number of officers who had been detailed for instruction at the School of Fire for a long time rather felt they should have been sent overseas. They decided to accept General Lawson’s invitation ‘to use all possible ingenuity in designing floats.’ Therefore, they had a huge sign painted which they intended to carry. It read: ‘Lawson for President. He kept us out of war.’ Their float was deleted by the censor.”

The parade continued with more floats featuring artillery, a field oven baking army bread, and ambulances. Archibald concluded:

“Some idea of the size of the parade can be obtained by the fact that it took over three hours to pass a given point.

All told, it was a very awe-inspiring spectacle, although it was only a small part of the total fighting material of the country and only the smallest fracton of the total employed by the Allied forces in Europe.”

After the war, Archibald became a professor of agriculture at Rutgers and taught vocational agriculture at New Brunswick High School. He died in 1946.

The Rutgers War Service Bureau was formed in 1917 as a way to keep Rutgers men serving in the war in touch with Rutgers and each other. It was headed by Earl Reed Silvers (class of 1913), who was assistant to Rutgers president William Henry Steele Demarest. Thanks to a grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, the letters are now available online.

Be sure to visit What Exit? between November 1 and 11 for new stories and follow highlights on Special Collections and University Archives’ Facebook and Twitter.

(With assistance from Tara Maharjan. Archibald photo from the Lauren S. Archibald Collection at Special Collections and University Archives [R-MC 119])