by Helene van Rossum

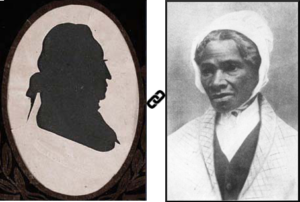

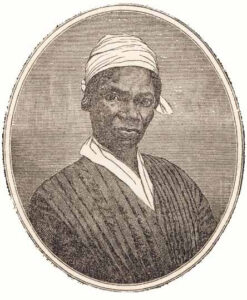

In February 2017 Rutgers University announced that it will name an apartment building on its historic New Brunswick campus after the abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth (c.1797-1883). The decision followed research findings, published in Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History, that Sojourner Truth had been enslaved as a child to members of the family of Rutgers’ first president Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh (1736–1790). However, Sojourner Truth–who was born with the name Isabella–never lived in New Jersey but grew up in Ulster County, New York. She was born enslaved to Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh’s brother, Johannes Hardenbergh Jr. (1729-1799), after whose death she and her family became the property of his son Charles. Johannes Jr. has been confused with his father, Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh (1706-1786), a founding trustee of Queens (later Rutgers) College. Not only did they share a name and lived in Hurley, near Kingston. Both also had a son named “Charles” and served as “Colonel” in the Revolutionary War.

The narrative of Sojourner Truth: “Colonel Ardinburgh”

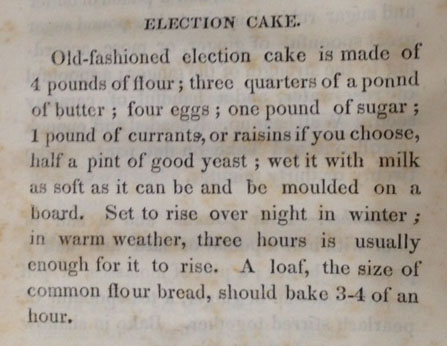

Sojourner Truth, who never learned to read or write, dictated her life’s story to fellow abolitionist Olive Gilbert (1801-1884), which was published as the Narrative of Sojourner Truth in 1850. According to Gilbert (who spelled the names that Truth provided as she heard them), Isabella was “the daughter of James and Betsey, slaves of one Colonel Ardinburgh, Hurley, Ulster County, New York.” After his death, Isabella, her parents, and “ten or twelve other fellow human chattels” became the legal property of his son Charles. Not older than two when her first owner died, Truth only remembered her second master. When he died too, she was about nine years old and was auctioned off to John Neely, a storekeeper who lived in the area. Her new master severely beat her because of her inability to understand orders. Having been raised in a Dutch Reformed household, she had only learned to speak the language of her masters: Dutch.

“That class of people called Low Dutch”

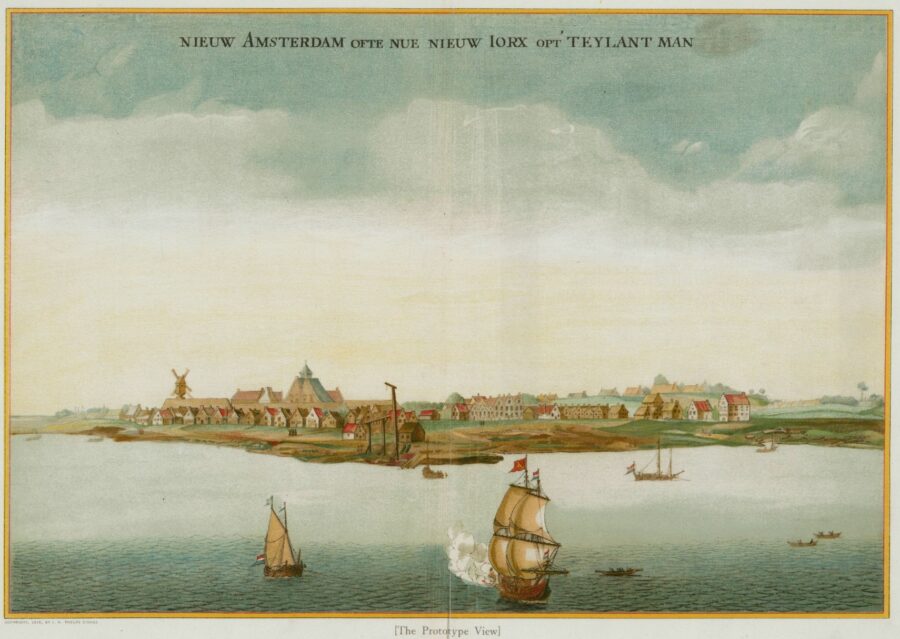

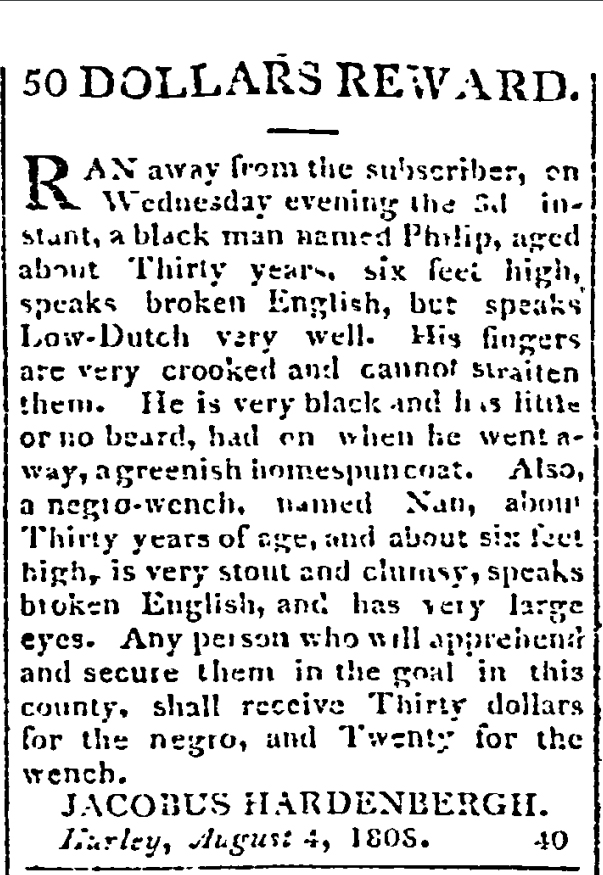

According to the Narrative Isabella’s first two owners “belonged to that class of people called Low Dutch.” These people were descendants of Dutch Reformed families who had emigrated from the Netherlands (the “Low Countries”) in the 17th century and settled in New York and New Jersey. Uninhibited by their Dutch Reformed faith, they farmed their lands with the help of enslaved blacks, like their English-speaking neighbors. (Read about the farm ledgers of Johannes G. Hardenbergh). In 1707 the grandfather of Sojourner Truth’s owner, also named Johannes Hardenbergh (1670–1745), had purchased a tract of two million acres of land in the Catskill Mountains from a leader of the Esopus Indians. For this land (spread across today’s Ulster, Sullivan and Delaware Counties) Hardenbergh and six others were granted a patent in 1708, which became known as the “Hardenbergh Patent.” By the time of the first federal census of 1790, fifteen heads of Ulster households had the name “Hardenbergh,” of whom ten listed enslaved people. Advertisements for runaway slaves in the Hudson River Valley (including three from members of the Hardenbergh family) indicate that many slaves spoke Dutch as well as English. Sojourner Truth herself always kept a distinct low-Dutch accent, and never had the Southern black accent that the white abolitionist Francis Gage gave her when publishing the speech that became known as “Ain’t I a Woman?” (compare this speech, written 12 years after the original speech, with a more authentic version).

Col. Johannes Hardenbergh (1706-1786), Rosendale, Hurley

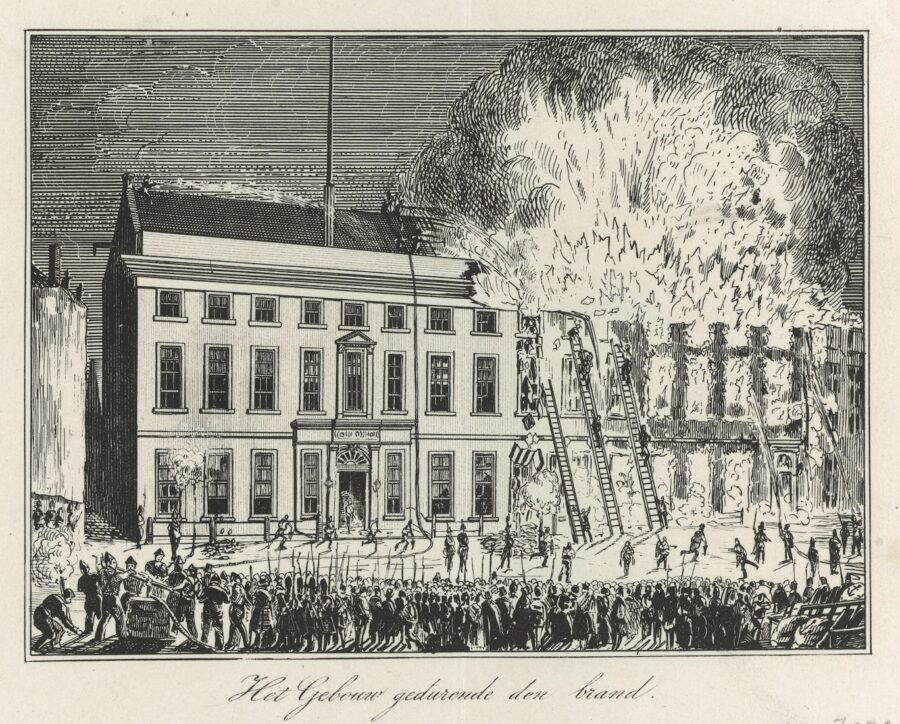

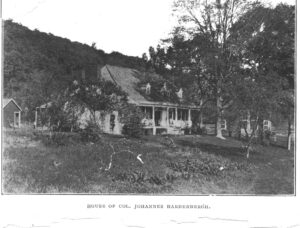

As can be seen in Myrtle Hardenbergh Miller’s The Hardenberg family; a genealogical compilation (1958) many male members in the Hardenbergh family inherited the name of the Hardenbergh patriarch in Ulster County. Miller makes a clear distinction between the older Colonel and the younger Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh (1729-1799), the owner of Sojourner Truth. But the older Colonel Hardenbergh (1706-1786) was more famous: he was a field officer under George Washington in the Continental Army, and served in New York’s Colonial Assembly. He lived with his family in “Rosendale,” a house with many rooms as well as slave quarters, formerly owned by his grandfather Colonel Jacob Rutsen. The house, in which Colonel Hardenbergh entertained Washington in 1782 and 1783, burned down in 1911. In the New York Census of Slaves of 1755 Hardenbergh is listed as living in Hurley owning six slaves, which made him one of the largest slaveholders in the county. In 1844 Hurley’s town boundaries changed, however, and the house became part of the newly formed town Rosendale. (View a map of Ulster county, 1829)

Col. Johannes Hardenbergh Jr. (1729-1799), Swartekill, Hurley

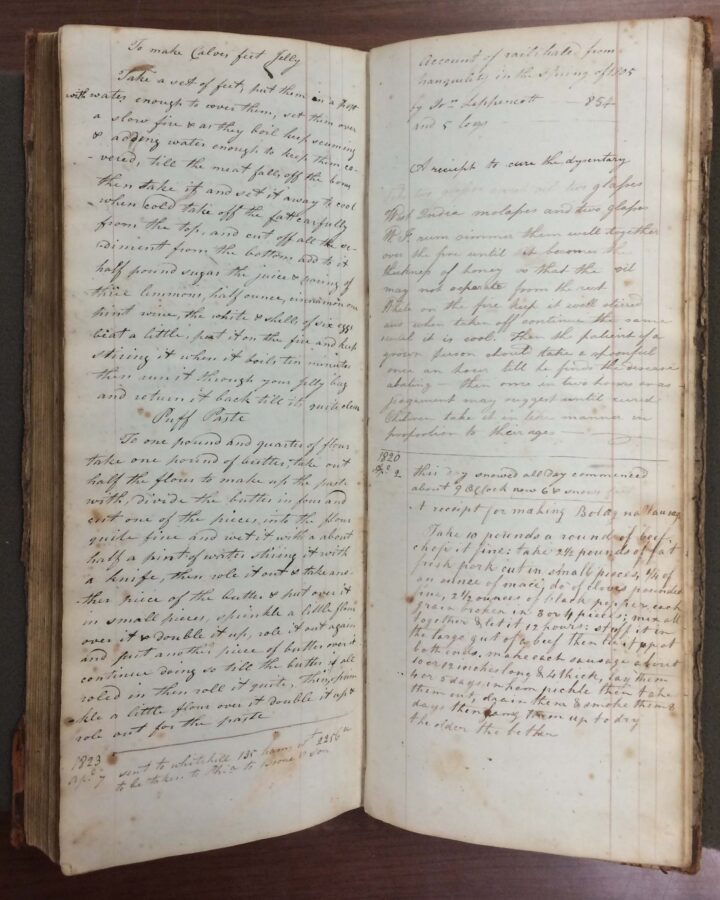

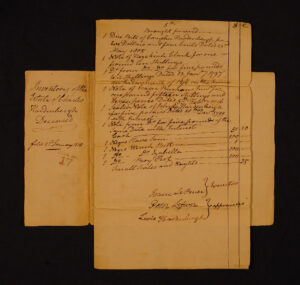

The younger Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh was lieutenant Colonel of the Fourth or Middle Regiment, Ulster County in August 1775, and received his appointment as Colonel in February 1779. Married to Maria LeFevre, he lived with his family in Swartekill, Esopus, which was a short distance north of Rifton and also part of the town of Hurley. Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh Jr. appears in the 1790 census for Hurley with seven slaves, who must have included Isabella’s parents James and Betsey and possibly siblings of Isabella who were sold before she was born. It was his son Charles who inherited Sojourner Truth and her family. Born in 1765, he was married to Annetje LeFevre and died in 1808. The inventory of his estate, written on May 12, 1808 and filed on January 2, 1810 lists “1 negro slave Sam, 1 negro wench Bett, 1 d(itt)o Izabella (and) 1 d(itt)o boy Peet.” Isabella, Peter, and the man named Sam were valued at 100 dollar but Isabella’s mother Bett was only valued at one dollar. Rather than being sold, she was freed so that she could take care of her old and sick husband, James Bomefree. Sadly, as recounted in The Narrative, “Mama Bett” (spelled as “Mau-mau Bett” by Olive Gilbert) preceded him in death, and he died in miserable circumstances.

Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh (1736–1790)

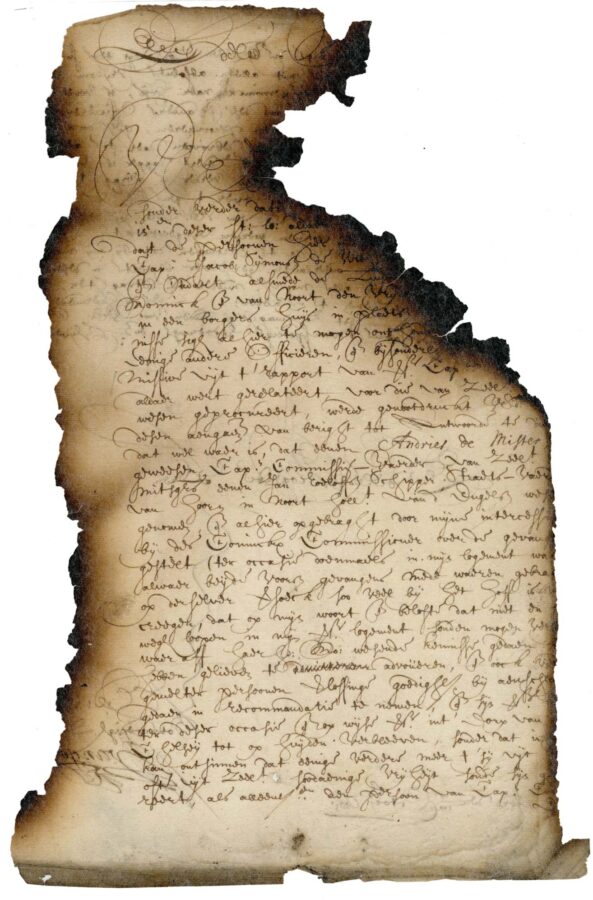

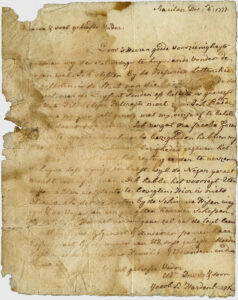

Like his brothers and sisters, Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh was born in the family home “Rosendale.” He left home when he was around seventeen years old to prepare for the ministry at the home of John Frelinghuysen (1727-54), a young prominent Dutch Reformed minister, who served five congregations in central New Jersey, and lived in what is now known as the “Old Dutch Parsonage” in Somerville. When Frelinghuysen unexpectedly died in 1754 the young Hardenbergh took over the five pulpits. He married Frelinghuysen’s much older widow, the pietist Dina van Bergh (1725–1807) in 1756 and was ordained to the ministry in 1758. Whether he also retained the three slaves (including a child), whom Dina had inherited according to her first husband’s will, is not known. But they did have at least one slave at the parsonage: in a letter from Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, written (in Dutch) to his father in 1777, he wrote that he had to hurry “because the negro is getting ready to go” (“wijl de neger gereet maakt om af te gaan“).

In 1781 Hardenbergh was called by the congregations of Marbletown, Rochester, and Wawarsing in Ulster county, and left New Jersey to move back into his parental home “Rosendale” with his family. He returned to New Jersey in 1786 to serve as minister in New Brunswick and president of Queen’s College. Whether he maintained any enslaved people during these last four years of his life we do not know. There are no slaves mentioned in his will.

This blog post was extracted from the presentation “Land, Faith and Slaves: the shared heritage of the Hardenbergh family, Rutgers University, and the Dutch reformed Church on June 17, 2017