We’re happy to report good news from Special Collections and University Archives: Improved access to our resources and expanded researcher hours and capacity. The main phase of moving our collections has been completed so most of our manuscript collections are accessible to patrons. We retained frequently used collections in Alexander Library and can provide access to the majority of material stored offsite. Retrieval does take longer than usual so advanced notice is required for appointments.

We have expanded our reading room hours and are now open Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday 10 am -12:30 pm and 1:30 pm – 4 pm, by appointment only. Likewise, we look forward to increasing our reading room capacity by June, when we move to a larger space on the first floor of Alexander.

Please see the SC/UA Migration Project: Seeking Higher Ground web page for regular updates on our move.

If you have questions about availability of specific material or would like to make an appointment, please contact us.

Category: Uncategorized

SC/UA’s Limited Reopening

Good news! On Tuesday, February 15th, Special Collections and University Archives will open a small Reading Room in Alexander Library. Initially the Reading Room will be open Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 10-12:30 , and 1:30-4. Advance appointments are required. Walk in patrons will not be admitted. Requests for material will take longer than usual and some material will not be available due to our ongoing collections move. Rare books, with the exception of 100 books, are inaccessible.

Up to two patrons–current Rutgers faculty, staff, and students only–can be accommodated at a time. These limits are based on the Return to Rutgers policies for visitor access and spacing and will be updated as Rutgers guidelines evolve. Please consult with an SC/UA faculty or staff member about scheduling an appointment.

Happy New Year from Special Collections & University Archives!

As we return from the holiday break, we continue our collections move and prepare for the semester ahead.

We’d like to take a moment to remind readers of digital resources we have available while our services remain limited during our move.

Our Digital Resources Guide brings together all currently available Special Collections and University Archives (SC/UA) digitized materials, as well as digital resources outside of Rutgers that are related to our work and that we frequently use. Two new additions to the Guide are:

- Personal Correspondence of the Rutgers College War Service Bureau, a project led by Digital Humanities Librarian Francesca Giannetti that features selected correspondence from the War Service Bureau, established in August 1917 to keep Rutgers students in contact with the college as well as with one another during the Great War. The correspondence has been transcribed, edited, and encoded by students of Rutgers–New Brunswick and Rutgers Future Scholars.

- Digital Scriptorium is a consortium of American libraries and museums that makes pre-modern manuscript materials freely available online. SC/UA’s contributions include manuscript fragments, leaves, and bound volumes spanning the 9th through 16th centuries, nine countries, and seven languages, primarily Latin.

SC/UA’s Primary Source Highlights is a growing collection of high-resolution images and selected PDF’s that represent our rich holdings across our collecting areas.

We are always working to digitize more materials, so check the Digital Resources Guide and Primary Source Highlights periodically for new additions.

The Banned Books of Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives

Originally posted on the Books We Read blog.

Books have been banned, challenged, censored, or even burned by organizations, schools, and parent organizations for a number of reasons. What defines a banned or a challenged book? A banned book is one that has been removed from the shelves completely. Books that have been challenged are an attempt by a person or group to remove or restrict materials to protect others. Books have been challenged for being considered “sexually explicit,” for having “offensive language,” or for being “unsuited to any age group.” At Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives, we have a collection of over 53,000 books, pamphlets, and broadside. With that many books in our collections, we have a number of books that have been banned over the years. Here are a few books from our collections and why they were banned.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been a controversial book since its first printing in 1884. The Concord Public Library banned the book in 1885 for its “coarse language” and today it continues to be challenged/banned for its use of racial stereotypes and slurs.

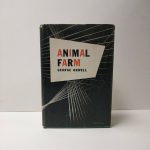

The book was completed in 1943 but could not find a publisher because of its criticism of the USSR, an important ally during WWII. It was finally published, but was banned in the USSR and other communist countries. The book is still banned today in North Korea, and censored in Vietnam.

Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England by John Milton

Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England by John Milton

John Milton wrote Areopagitica in 1644 to argued for the freedom of speech and expression and opposing the licensing and censorship by the English Parlament.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

According to The Guardian, Brave New World is among the top ten books Americans want banned for its contempt for religion, marriage and family, as well as its references to sex and drugs.

Candide by Voltaire

Candide by Voltaire

Candide was another book which was banned upon its release in 1759 by the Great Council of Geneva and the administrators of Paris. It was later banned in the United States in 1930 for obscenity.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto was banned by many countries around the world to prevent the spread of communism.

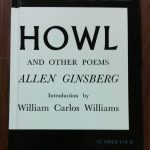

The poem was part of a 1957 obscenity trial for the topics of illegal drugs and sexual practices. A California State Superior Court ruled that the poem was of “social importance,” and dismissed the case.

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

This poetry collection was considered obscene upon its release in 1855. Libraries refused to buy the book, and the poem was legally banned in Boston in the 1880s and informally banned elsewhere.

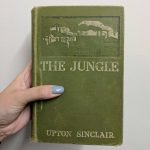

The Jungle was banned in a number of counties around the world including Yugoslavia, South Korea and East Germany. The Nazi party in Germany actually burning the book in 1933 because of the socialist views.

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Of Mice and Men is often found on the American Library Association’s list of banned books for its use of racial slurs, profanity, vulgarity, and offensive language.

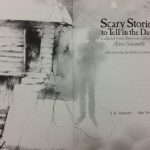

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz

This series of children’s books based on folklore and urban legend is on the American Library Association’s list of most challenged series of books from 1990–1999 and is listed as the seventh most challenged from 2000–2009 for violence.

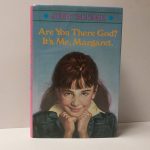

Tiger Eyes and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret both by Judy Blume

Tiger Eyes was challenged for its depiction of violence, alcoholism, and discussion of suicide. Whereas, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was challenged for sexual references and alleged anti-Christian sentiment. Judy Blume is the second most challenged author, only following Stephen King. Her books are often challenged by parents and religious groups for her writings about puberty, masturbation, birth control, and teenage sexuality.

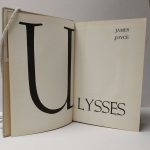

Ulysses by James Joyce

Ulysses was banned in the U.S. until 1934 because of obscenity. That would be this 1924 fifth printing of the first edition of Ulysses owned by Selman Waksman.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was banned in the American south preceding the Civil War for holding pro-abolitionist views and arousing debates on slavery.

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections, Part Three

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

This is the third and last post in a short series featuring final projects from the Rutgers Byrne First-Year Seminar I taught in Fall 2020, “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture.” You can read about the course and the final project, in which students envisioned their own pop culture archives, and check out other student projects, here.

This project, An Old Way to Listen to Music: Archiving a CD Collection, by Carmen Ore, Rutgers Class of 2024, wraps up the series with a consideration of how one’s connection to a particular type of music can extend to the media form.

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections, Part Two

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

This is the second in a short series featuring final projects from the Rutgers Byrne First-Year Seminar I taught in Fall 2020, “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture.” You can read about the course and the final project, in which students envisioned their own pop culture archives, in this post.

This project, entitled Archiving Goodness, is by Sarah LaValle, Rutgers Class of 2024. Sarah’s archive, like our previously featured student’s archive, Domination of Face Masks in 2020, is another timely project that came out of this course.

Teaching in the Archive: Rutgers First-Year Students and Popular Culture Collections

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

For the past two fall semesters, I have taught “Examining Archives Through the Lens of Popular Culture,” a course I developed for the Rutgers Byrne First Year Seminars. In the course, students engage in active, hands-on learning to explore archives and special collections and how they can be used for research. We examine popular culture collections in Rutgers’ Special Collections and University Archives and elsewhere that document a wide range of topics such as the New Brunswick music scene, video games, cookbooks and restaurant menus from around the Garden State, zines representing a variety of subcultures, Women’s March and other protest movement posters, and Jersey Shore memorabilia.

The goals I set for students in this course include developing an understanding and appreciation of archives and special collections; developing primary source research skills and becoming careful interpreters of documents, images, and objects; understanding how critical factors such as ethnicity, race, gender, and class are documented and perpetuated in popular cultural materials; and to learn to think about what is included and excluded in archives and special collections, and why. We also learn from each other as we share, debate, and think creatively about expressions of popular culture.

I will be sharing some of the students’ final projects (some anonymously) for the Fall 2020 course, in which they envision their own pop culture archive, and present their concept for an archive, in narrative form or in a slide show.

Here is our first student project, a very timely archive, entitled Domination of Face Masks in 2020.

2021 Greetings

By Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services

Happy New Year from Special Collections and University Archives. In early 2021, we are reflecting on the fact that that 2020 was a difficult and challenging year for so many. Like most of our colleagues in archives and special collections around the country, and indeed around the world, Special Collections and University Archives (SC/UA) faculty and staff have had to redirect our efforts to increase remote services. In summer and fall 2020, we scrambled to enhance access to digital materials, offer Zoom research consultations, and provide remote classroom instruction. We probably made more PDF copies of materials for researchers than any year to date!

While we look forward to the day we can reopen our reading room to researchers near and far, we continue to provide research support, instruction, and information for enjoyment and edification as our faculty and staff work (primarily) remotely. To that end, we’d like to share a few highlights of the work we have been doing to support Rutgers faculty, students, and staff; researchers around the state of New Jersey; and students and scholars from all corners of the world.

Digital Resources

We are excited to share a new digital resource, “Special Collections and University Archives Primary Source Highlights,” a site that makes accessible a trove of images we have scanned for researchers over the years. The site also features images from an ongoing project to scan the Sinclair New Jersey Postcard Collection. While “Primary Source Highlights” is still in its infancy, we are adding images regularly, so we encourage you to check back periodically.

“Primary Source Highlights” will be included in the SC/UA Digital Resources Guide we created in the fall. This guide continues to serve as a one-stop-shop for centralized, easy access to SC/UA’s digitized resources.

During the fall semester, we started a project to revamp and update the content of our subject guides. These guides serve as a useful gateway to our collection strengths, and are a particularly good resource for students looking for paper topics, or to see what materials SC/UA holds on a particular topic.

The New Jersey Digital Newspaper Project is continuing to digitize historical New Jersey Newspapers for inclusion in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America website. Recent additions include the Gloucester County Democrat (1878-1912), Morris County Chronicle (1877-1914), Pleasantville Weekly Press (1892-1911) and The Pleasantville Press (1912-1914).

The NJ Digital Newspaper Project blog provides further information about the project and links to all NJ newspapers digitized to date. These newspapers have been digitized as part of the National Digital Newspaper Program, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Reference and Instruction

We will continue to provide instructional support this spring. If you’re looking for resources for your course, or would like a curator or archivist to provide instruction for your class, feel free to send a message to scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu and your request will be directed to the appropriate faculty or staff member. For general requests or questions, feel free to contact Christie Lutz, New Jersey Regional Studies Librarian and Head of Public Services at christie.lutz@rutgers.edu.

Looking for a quick way to introduce your students to the mission and work of SC/UA, or add a video to your Canvas course? We’ve compiled our videos, including a brief overview of SC/UA aimed at undergraduate students, and a couple of fun quizzes which in one spot. Check out https://libguides.rutgers.edu/scuavideos

You can always write to our reference account at scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu with questions and scanning requests. We are continuing to waive our reproduction fees this semester.

Exhibits and Events

2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) granting women the right to vote. Explore our most recent exhibition, On Account of Sex: The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage in Middlesex County or listen to a talk by Ann D. Gordon, “Bringing the Story Home: Agitating for Woman Suffrage in New Jersey.”

Photographer and author Barbara Mensch delivered the 34th annual Louis Faugères Bishop III lecture, “In the Shadow of Genius: The Brooklyn Bridge and Its Creators,” in November, 2020. Mensch was inspired by SC/UA’s Roebling collection to create her recent book by the same name (Fordham University Press, 2018).

What else is happening?

We’re starting to roll out a new look and feel to our finding aids, via ArchivesSpace, a platform that will provide easier searching of our manuscript collections and a uniform look and feel.

Along with the rest of Rutgers University Libraries, we are developing a new website that will be more user-friendly and feature updated content.

You can always check the SC/UA website and social media feeds (links in the column to the right, plus the New Brunswick Music Scene Archive on Facebook) for the latest news, events, and changes in operating status and/or services.