We have seen lots of museums and galleries showing off their collections and exhibits online, including our friends at the Zimmerli Art Museum showing off their Everyday Soviet exhibit. Here are some of our exhibits that you can explore from anywhere:

Digital Exhibits:

- All Aboard! Railroads and New Jersey, 1812-1930: https://exhibits.libraries.rutgers.edu/nj-railroads

- Badian Collection: Coins of the Roman Republic: https://collections.libraries.rutgers.edu/roman-coins

- Clifford P. Case II: Loyal Son, Scholar, Statesman: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/exhibits/case/index.shtml

- Crossroads: Harrision A. Williams, Jr. and Great Society Liberalism, 1959-1981: https://exhibits.libraries.rutgers.edu/crossroads

- Education and The Book Arts in New Jersey, or, Preaching What We Practice: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rulib/abtlib/danlib/bookarts/ba-hand.htm

- Garden State Harvest: New Jersey’s Agricultural Heritage: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/exhibits/garden_state_harvest/garden_state_harvest.html

- John Milton and the Cultures of Print: An Online Exhibit of Books, Manuscripts, and Other Artifacts: https://exhibits.libraries.rutgers.edu/milton

- Livi at 50: A Celebration of Livingston College’s 50th Anniversary: https://collections.libraries.rutgers.edu/livingston-at-50

- Miriam Schapiro Pop-Up Exhibit: https://libguides.rutgers.edu/schapiroexhibit

- New Jersey INTERNATIONAL Book Arts Symposium: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/libs/scua/bookarts/photographs/frontpage.html

- On the Banks of the Raritan: Music at Rutgers and New Brunswick: https://exhibits.libraries.rutgers.edu/music-on-the-banks

- The Pivotal Right: Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Women’s Right’s Convention at Seneca Falls: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/libs/foster/pivotal_right/pivotal_right.shtml

- The POP-UP World of Ann Montanaro: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/libs/scua/montanar/p-ex.htm

- @Rutgers_SCUA: Social Media and Archives: https://go.rutgers.edu/krgtqw9j

- Struggle Without End: New Jersey and the Civil War: https://exhibits.libraries.rutgers.edu/struggle-without-end

- Lynd Ward’s Vertigo: http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/Vertigo/

Exhibit Catalogs:

- All Aboard: Railroads and New Jersey, 1812-1930: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/36150/

- Archival Assemblages: Rutgers and the Avant-Garde, 1953-1963: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/42473/

- Benevolent Patriot: The Life and Times of Henry Rutgers: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/42477/

- Book Arts in New Jersey: Seven Contemporary Perspectives: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/42476/

- Celebrating the Tradition: 30 Year of Queer Activism at Rutgers: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/42469/

- Early Roman Coinage of the Republic: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/41378/

- Fairweather Occult Collection: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/45405/

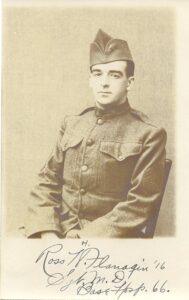

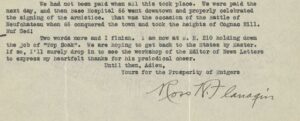

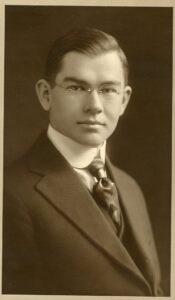

- “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken!”: New Jersey in the Great War: https://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/scua/Heaven_Hell_or_Hoboken_Catalog.pdf

- John Milton and the Cultures of Print: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/31285/

- New Jersey and the Civil War: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/43226/

- On the Banks of the Old Raritan: Music at Rutgers and New Brunswick: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/57989/PDF/1/play/

- Philosopher, Engineer, Tycoon: John A. Roebling and his Legacy: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/42471/

- Reprise: John Milton and the Cultures of Print: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/31285/

- Rutgers University 250th: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/49504/

Exhibit Talks:

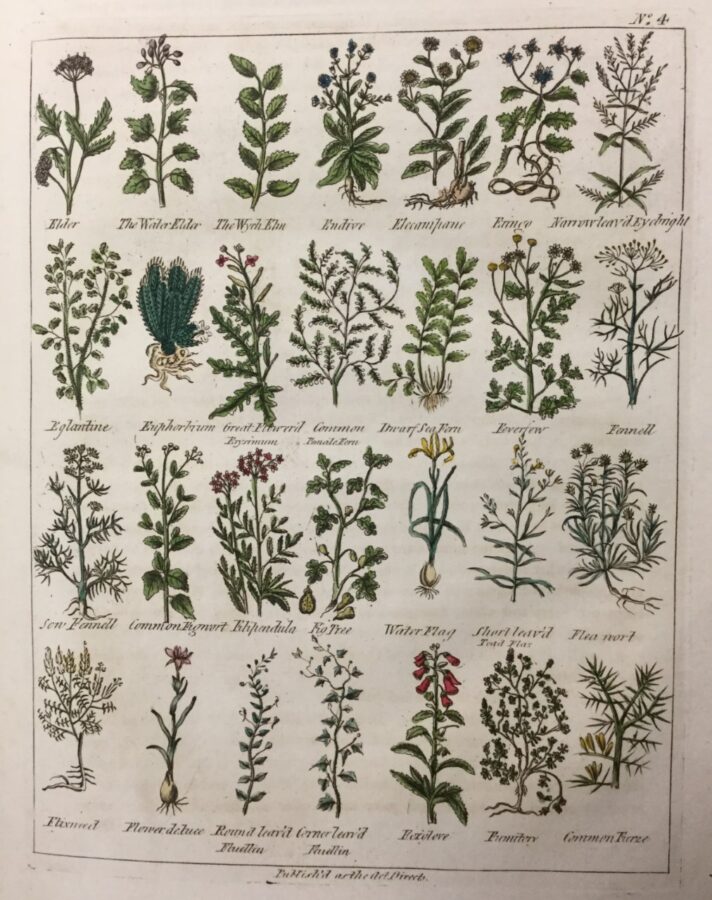

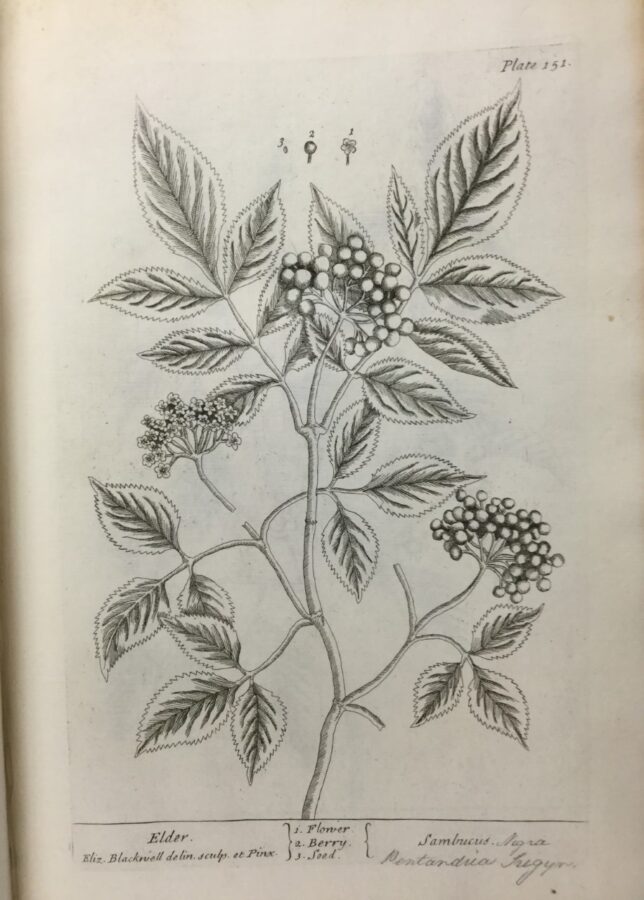

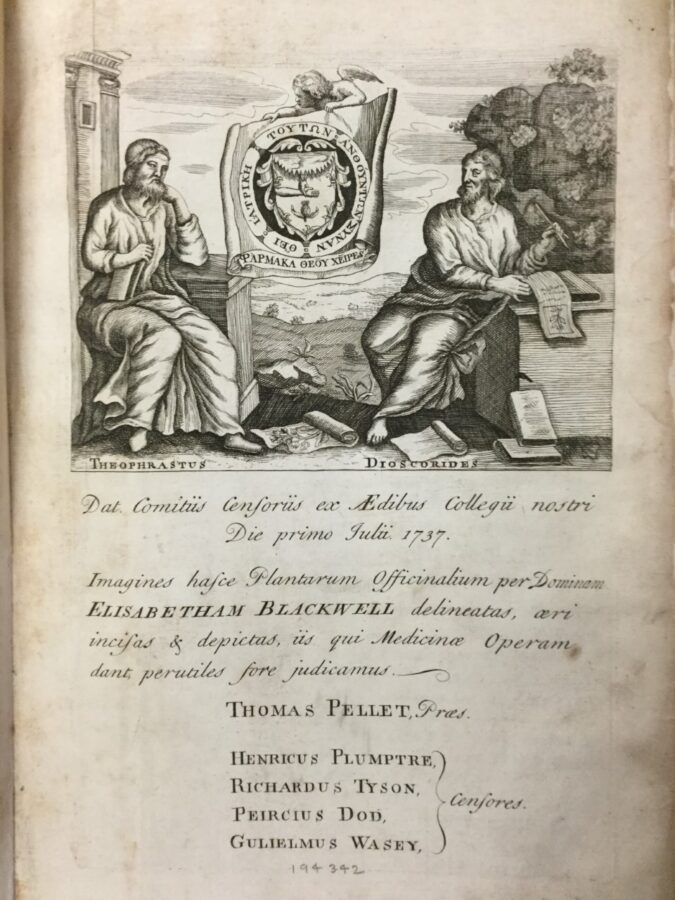

- The Art of Healing: Early Herbals from Rutgers University Libraries Collections: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/47112/

- New Jersey and the Civil War: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/38692/

As always we are available on social media and email (scua_ref@libraries.rutgers.edu).