In 2018, the Douglass Residential College (DRC) celebrated the 100th anniversary of the college’s founding. The anniversary generated many programs and publications that extended into 2019 and 2020. For instance, in October 2019, Women Artists on the Leading Edge: Visual Arts at Douglass College by Joan Marter, Rutgers Distinguished Professor Emerita, was published by the Rutgers University Press. Aware of the college’s long history as a leader in visual arts pedagogy, Douglass Dean Jacquelyn S. Litt provided funding to support additional research by DRC students. We are delighted to share the results of Hallel Yadin’s research in this blog. Hallel is currently an Archives Associate at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York.

Professional and Academic Training in the Fine Arts Program at NJC, 1920-1952

Hallel Yadin, DRC ‘19

Introduction

In its early days, New Jersey College for Women (NJC) was the only non-normal school (teacher’s college) option for New Jersey’s women. As such, it assumed some responsibility for preparing its students for the state workforce. Here lay some tension about its goals as an institution of higher education. While it fancied itself a small liberal arts college in the vein of Vassar or Sarah Lawrence, as per the sensibilities of its ever-decorous founder, Mabel Smith Douglass, the liberal arts did not always align with the needs of the state. The Fine Arts Department at New Jersey College for Women was one arena where this disconnect played out.

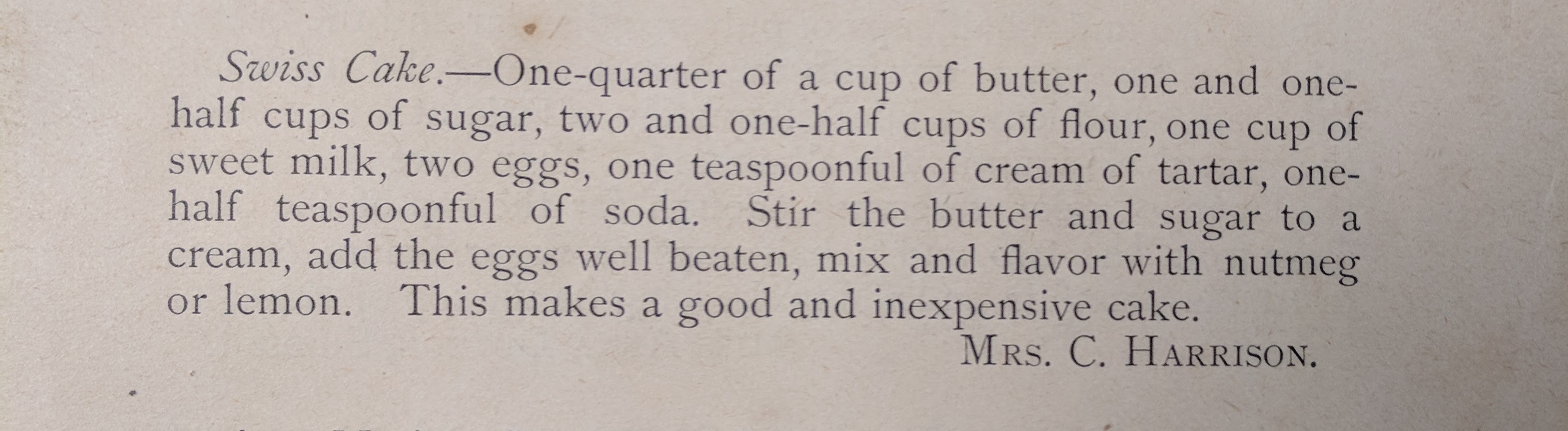

First, there were tensions related to art being regarded as a serious object of study in the academy. However, by the time NJC formed an art department, those had largely been alleviated. As Dean Mabel Smith Douglass wrote in 1930, “Long regarded by the colleges as merely a kind of adornment as far as solid education went, and as scarcely worthy of serious consideration, [art] has gradually, but surely, won its right to be considered, much as music, a serious study of dignity and importance and a reasonable, even an essential, part of a liberal education.” This reflects the description of the purpose of the art department in the 1930 course catalogue, which states, “The purpose of the department is (1) by the study and the appreciation of art to provide a part of a liberal education; and (2) specifically to prepare students to teach art or pursue it professionally.” This dual purpose demonstrates the department’s attempt to balance the demands of the liberal arts curriculum with the prerogative of NJC to prepare students for the workforce, especially as a public state institution.

Course Offerings

The art department began in the 1925-1926 academic year. For the first two years, its offerings were limited to art history courses:

❖ History of Ancient Art

❖ History of Early Christian and Medieval Architecture

❖ History of Italian Architecture and Sculpture

❖ History of Italian and Spanish Painting, History of Northern Painting

❖ History of Modern Art

A shift began in 1927 with the introduction of the Curriculum in Art for students preparing to teach “practical” art. This shift actually comprised two major developments: offers of pre-professional training in art-related fields, and the department distinguishing between practical, and, by default, “impractical” forms of art. In 1927, NJC began offering a “practical arts course,” specifically to train students to become art teachers.

The Practical Arts courses, divided into grade-level seminars, included the following topics:

❖ Color, Design, Freehand Drawing, and Perspective for sophomores

❖ Advanced work in color, drawing, and perspective for juniors

❖ Advanced work in color, drawing, and perspective for seniors

It makes sense that teaching would be the department’s first foray into arts-related vocational training, as teaching is the field that the plurality of NJC graduates pursued. A survey entitled “Vocational Interests of the Class of 1936” reported that 94 of the 203 respondents (which represented 90 per cent of the class) sought teaching positions. The next-highest response was work in department stores, with only 14 graduates. These figures are striking, especially since 32 respondents did not list career paths and likely were not planning to work at all.

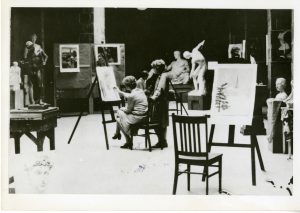

Furthermore, the fine arts courses expanded beyond history and theory into the process of creating art. Starting in the 1930s, the art courses included:

❖ General Art

❖ Art Appreciation

❖ Drawing and Composition

❖ Design

❖ Commercial Design

❖ Drawing and Painting

❖ Theory and Practice of Teaching Fine Arts

The language that the art department used to delineate between “professional” and “fine” art evolved over time, but the division remains throughout decades of course offerings. In the 1920s, the course catalog differentiates between “fine art” and “applied art.” In the 1930s, it shifts to delimiting descriptions of art offerings as “graphic and plastic arts,” which were defined only as “painting, modelling, drawing, and design.” The 1940s brought intradepartmental discussion of the “practical branches” of the arts. In the 1950s, the Division of Fine Arts was described as providing offerings in both the “cultural and professional arts.” While the language changed, the department consistently differentiated between professional or “practical” arts, and non-professional or “fine” arts, despite robust offerings in both within the same department.

The art department also offered training in several career tracks in more traditional trades. One of these was the major in art education noted above. NJC also offered majors in interior decoration, fashion design, costume design and illustration, and commercial design at varying periods in its history. Outside of the art department, there were other majors that seemed to be confined to “impractical” women’s work, but actually had quite practical applications, like the industrial clothing application in the home economics department. (Home economics as a whole actually included “real-world,” outside-the-home tracks, like industrial nutrition, which kept the country fed during the Second World War.)

Beyond this, between 1937 and 1952, the art department offered a major in ceramic arts. The major granted a Bachelor’s of Science degree in cooperation with the ceramics department at Rutgers College and offered “an outline of training in the applications of art to the ceramic industry, including studio work in art and laboratory work in ceramics, as well as detailed study of the nature and uses of clays.” (It is worth noting that in 1945 the Department of Ceramics at Rutgers joined the School of Engineering, while at Douglass it was relegated to the art department.) Without having identified much more detail, we can speculate that the offer of this major was related to Trenton’s renowned pottery and ceramics industry.

The Role of Art Instruction in Forming a State Cultural Identity

The college was cognizant of the role of higher education in individual states’ cultural identity formations. As one dean wrote, “It is no longer a question of whether or not the arts belong in the university. They are already established on the campus. The question, therefore, is one of how Rutgers can expand its facilities and services so that it can assume a position of leadership in the cultural affairs of the state. We need our own solutions to cultural needs, not those of New York or Philadelphia…” There was a similar sense of the urgency of equipping New Jersey within the Fine Arts Department itself. As one chair of the department wrote in 1941, “New Jersey, more than any other state, with the possible exception of New York, is pioneering on some frontiers of American democracy … Our state cannot wait to see what other states have done and follow their lead.” NJC assumed the responsibility of providing New Jersey with its arts training. In this

way, the arts came into a professional role, and not just in terms of workforce training. This was workforce training that was in service of the state.

The institution was also cognizant of the role of art in national identity. As early as 1939, Dean Margaret Trumbull Corwin wrote, “Closely associated with English and history in the preservation of our cultural traditions are the fine arts.” For example, in the 1939-1940 school year, the art department reprised an “Americanization” exhibition that had first been held a decade prior. “Students, awakening to the realization of the historical significance of much that surrounded them and was taken for granted in their daily lives at home, responded enthusiastically,” reported the chair of the department. “More than two hundred thirty articles from over thirty countries were assembled, – a graphic picture of the international family backgrounds in this cross-section of American life.” NJC was aware of the role of arts and culture in both state and cultural identity formation, which no doubt complicated how it perceived its institutional responsibility as the only public liberal arts-style college for women in New Jersey.

This pursuit, however, complicates the clear-cut distinction between fine and practical arts. The fine arts were understood to be a requisite element of this quite pragmatic state-level cultural project. The chair of the art department once wrote, “Our department at Douglass feels that we should not let the state public school art program rest entirely in the hands of the state colleges.” (He is presumably referring to the state’s teaching colleges.) This indicates a sense that fine arts offerings — which were NJC’s purview in a way that was not the case for the normal schools — were a necessary element of arts education. This concept muddles the dichotomy between “practical” and “impractical” art discussed above. If New Jersey College for Women was to position itself as a cultural authority and cultural producer in New Jersey, its fine arts programs were of paramount importance.

Photograph Notes, in order of photograph appearance

1. Mabel Smith Douglass, ca. 1918 Rutgers University Archives

2. Art studio at NJC, 1920s, Rutgers University Archives

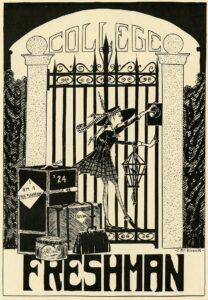

3. NJC students show their graphic arts skill in the yearbook, the Quair, 1921, Rutgers University Archives

4. Margaret Trumbull Corwin, ca 1950, Rutgers University Archives